by jhwildlife | May 23, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

by Max Frankenberry, JHWF Assistant Bird Bander

This past Saturday, May 19, 2018, JHWF staff participated in the annual Wyoming Game & Fish Department bird survey of the South Park Wildlife Habitat Management Area, just south of Jackson. Our group of volunteer birders, including enthusiastic Nature Mappers and Jackson Hole Bird & Nature Club members, met bright and early Saturday morning, led by our local bird nerd expert volunteer, Tim Griffith. Tim has been crucial to organizing Game & Fish bird surveys of the South Park area since 2016, which have so far logged 96 different species for the area! Our pack split into two groups, one to tackle waterfowl, shorebirds and raptors around the ponds, the other to take on “Warbler Alley,” the thick cottonwood tree groves hugging the backwaters of the Snake River to the southeast. What an appropriate nickname that was – Yellow Warblers dotted most every tree in South Park, and were joined by the radiant Yellow-rumped, Wilson’s and MacGillivary’s Warblers as well. It was a different traveler from the south, however, that took everyone by surprise.

‘Warbler’s neck’ is a common occurrence on a bird survey.

After a busy four hours of hiking and birding the survey was winding down, and brunch was on the brain. But birding tends to deliver the bombshells at the last moments, and Saturday was no different. Jon Mobeck, our team’s oriole-obsessed leader shouted. “Bullock’s! Wait… BALTIMORE!” In a low hawthorn tree not 50 feet from us, was not only a Bullock’s Oriole, a gorgeous but fairly common bird in Jackson Hole, but next to it was a Baltimore Oriole, a normally much more eastern cousin. Historical records vary, but this bird may be one of less than a dozen ever reported in the state of Wyoming, and likely less than a handful have ever been seen in Teton County. What a find! The Bullock’s and Baltimore seemed to follow each other, flying from tree to tree after one another. Perhaps the Baltimore had lost his way on his normal spring route up from Central America, noticed a bird that resembled his brilliant orange color, and followed that Bullock’s back to our western mountains, far away from his normal east-of-the-plains summer vacation.

A Baltimore Oriole (left) is a rare find in Jackson Hole. The Bullock’s Oriole (right) is more of a local. Photos: Kate Maley

It’s moments like these that make us realize how special close-to-home wild places like South Park are. The diversity of wildlife in these areas can be astounding. But problems exist in the fact that unless these places are studied or surveyed, we may never know the rarities or struggling populations there. This is the issue Nature Mapping Jackson Hole is helping to solve – by submitting data from your commute from work, a dog-walk in a Jackson city park or a backpacking trip through the Gros Ventre, you are helping to build our human community’s understanding of the wildlife community that surrounds us. And every data point really is significant! You don’t often find rare birds like the Baltimore Oriole, but it’s very possible that the deer you saw driving home could represent the beginning of a muley movement exploring a new feeding ground in Jackson Hole. The data you enter from these sightings help JHWF’s partners to prepare management decisions that inspire positive interaction between humans and the wildlife moving into these areas. Knowing that your effort can directly benefit our local species is a reward in itself, and who knows – maybe your attention to wildlife developed from Nature Mapping will lead you to that once-in-a-lifetime animal.

Max Frankenberry spots a Common Merganser on a back channel of the Snake River through Wingspan Optics binoculars.

South Park Wildlife Habitat Management Area Species Count 2018 Surveyed by 22 Participants

American Coot 3

American Crow 1

American Goldfinch 11

American Kestrel 13

American Robin 74

American White Pelican 38

American Wigeon 9

Bald Eagle 6

BALTIMORE ORIOLE 1

Bank Swallow 4

Barn Swallow 6

Barrow’s Goldeneye 16

Belted Kingfisher 4

Black-billed Magpie 9

Black-capped Chickadee 24

Black-headed Grosbeak 2

Blue-winged Teal

Brewer’s Blackbird 1

Broad-tail Hummingbird 2

Brown-headed Cowbird 6

Bufflehead

Bullock’s Oriole 4

Calliope Hummingbird 6

Canada Goose 114

Cedar Waxwing

Chipping Sparrow 2

Cinnamon Teal 47

Cliff Swallow 7

Common Merganser 37

Common Raven 15

Common Yellowthroat

Cooper’s Hawk 1

Dark-eyed Junco

Double-crested Cormorant

Dusky Flycatcher

Eared Grebe

Eastern Kingbird

European Starling 21

Gadwall 84

Gray Catbird 1

Great Blue Heron 6

Green-tailed Towhee 1

Green-winged Teal 2

House Wren 14

Killdeer 12

Lazuli Bunting

Lesser Scaup 7

Lincoln Sparrow

MacGillivary’s Warbler 3

Mallard 52

Marsh Wren 5

Mountain Bluebird

Mountain Chickadee

Mourning Dove

N. Rough Wing Swallow 11

Northern Flicker 19

Northern Shoveler

Orange-crowned Warbler 2

Osprey 6

Pied-billed Grebe

Pine Siskin

Redhead Duck

Red-naped Sapsucker

Red-tailed Hawk 6

Red-winged Blackbird 62

Ring-billed Gull 2

Ring-necked Duck 12

Ruby-crowned Kinglet 7

Ruddy Duck 4

Sandhill Crane 3

Savannah Sparrow 6

Sharp-shinned Hawk

Song Sparrow 51

Sora 3

Spotted Sandpiper 24

Swainson’s Thrush 1

Tree Swallow 219

Trumpeter Swan 2

Turkey Vulture 6

Vesper Sparrow 2

Violet-green Swallow 3

Virginia Rail 1

Western Meadowlark 3

Western Tanager 1

Western Wood Pewee

Western/Clark’s Grebe

White-breasted Nuthatch 1

White-crowned Sparrow 3

White-faced Ibis

Wilson’s Phalarope

Wilson’s Snipe

Wilson’s Warbler 1

Wood Duck

Yellow Warbler 130

Yellow-headed Blackbird 37

Yellow-rumped Warbler 94

Species Total 68

by jhwildlife | May 14, 2018 | Blog, Wildlife Friendlier Landscapes

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

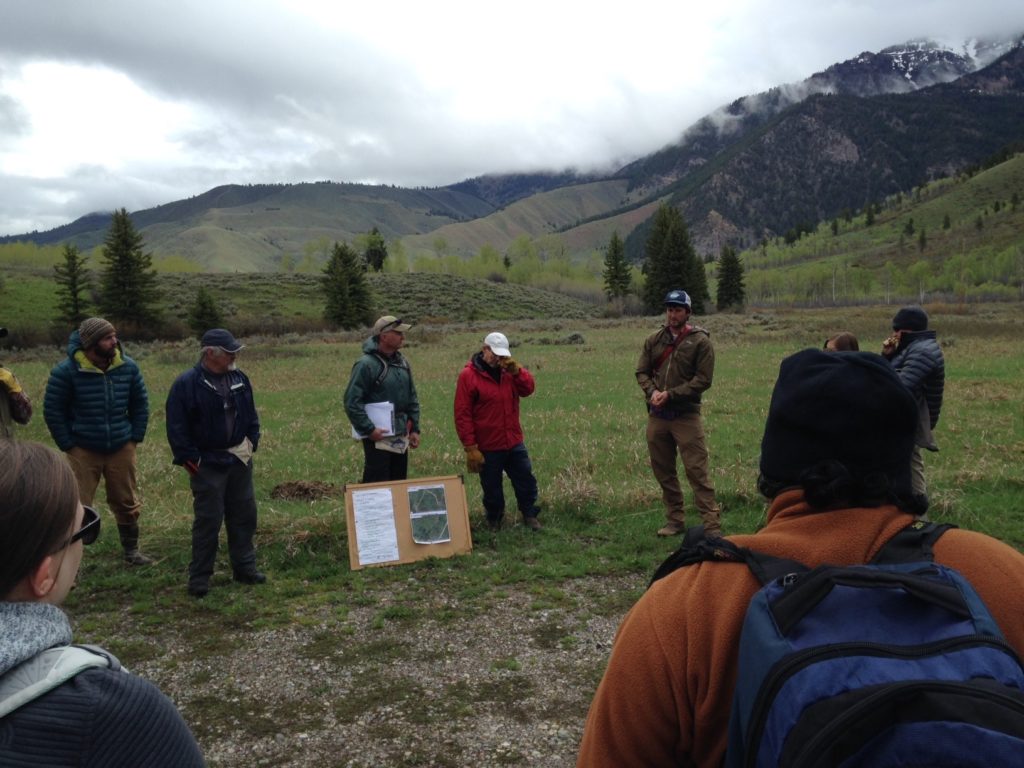

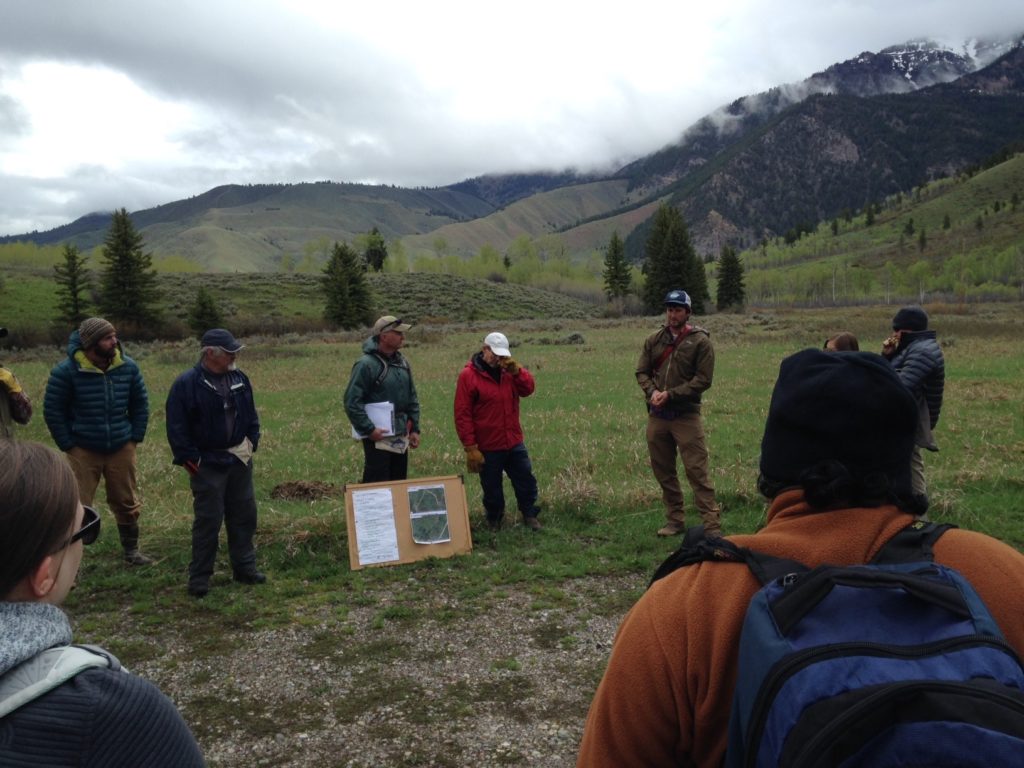

A steady rain saturated the ground as I looked out the window. It was 5:30 a.m. on the day of a fence pull – Saturday, May 12. It’s hard not to feel that a bit more sleep would be a better choice than pulling down barbed wire fences, but that fleeting thought is dismissed as I think about the others who are doing – and maybe thinking – the same thing. I’ve done this work in the rain before, but nowhere near as many times as those key “Fence Team” volunteers who I would join later that morning. And then I have the thought of all the people who have done this over the past two decades, in all sorts of weather conditions, in any terrain. There was never really a doubt that we would pull down fence that day.

On this day, we were scheduled to benefit from a large volunteer crew generously offered by EcoTour Adventures. EcoTour was hosting a group of 16 students from a school in Louisiana along with an equal number of parents. While visiting (vacationing) here, the Louisianans would see the typically amazing sites of Jackson Hole, experience exhilarating adventures, and learn about the area’s wildlife and natural gifts from EcoTour’s exceptional guides. Because of EcoTour’s commitment to the area’s wildlife, they encourage their guests to participate in activities that help preserve what makes this place special.

On this day, though, with rain coming down and more rain forecast throughout the day, I had assumed that the group would cancel, and I wouldn’t have blamed them for a second. After all, they were on vacation. Pulling down barbed wire fences in the rain is not high on the “to-do” list for most of the vacationing public.

So at 7:22 a.m., when EcoTours CEO Taylor Phillips texted: “OK we are all in for the fence pull. Expected arrival 9:15. Yahoo!” I was surprised. I knew I would be meeting our indefatigable Fence Team volunteer leaders Gretchen, Steve and Randy since we had all decided that we were going no matter the weather, but now the prospect of our small team working through the rain turned into the excitement of a huge group (41) of us doing so together.

As it turned out, the rain was relatively light throughout most of the project, and I was amazed by the resilience of the Louisianans. I suppose they are accustomed to rain, but as one of the parents – James – said, “We don’t get to do anything like this in Louisiana.” The Louisianans worked for 3 hours with us, and it sure seemed like they were having a good time. That knowledge filled me with joy. Here all of us were, in the rain, removing barbed wire fences to make things easier for wildlife. And it was fun! And it reminded me of how great it is to share such an experience with new people, from a different place. We’re all so similar, and we all can do so much together!

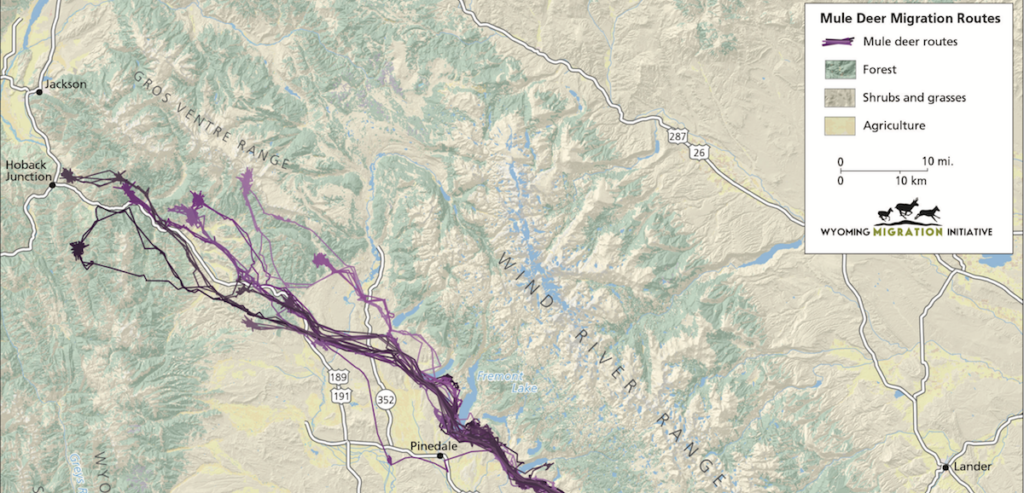

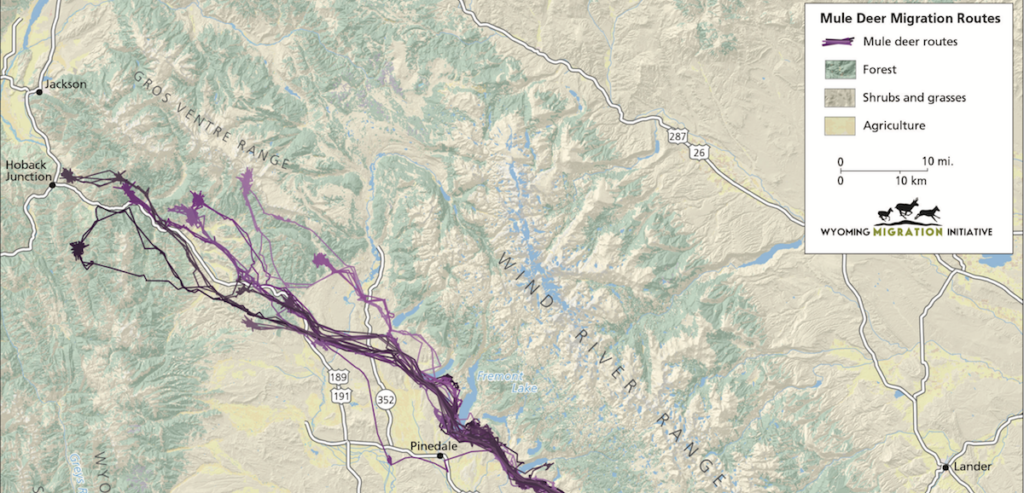

Of course, we do this for the wildlife. On this occasion, we worked in an area at the northernmost end of the recently mapped Red Desert-to-Hoback Mule Deer Migration Route. The Wyoming Migration Initiative elucidated this 150-mile route through extensive GPS collaring and subsequent mapping that is now recognized and discussed around the world. Each spring, mule deer that were once thought to be a resident population of the Red Desert region migrate across and through many roads, houses, industrial developments, and about 100 fences before finding summer range in the greater Hoback area. We worked near those summer ranges, where they will spend considerable time, removing obstacles that can separate fawns from does, and just generally make their route more challenging.

The northern end of the Red Desert to Hoback Mule Deer Migration Route, as identified by Wyoming Migration Initiative, which includes summer range for mule deer.

We were on Bridger-Teton National Forest Land, where we removed about ½ mile of nasty barbed wire fences. It is a privilege to be able to support our agency partners who couldn’t possible deploy enough staff members to remove or maintain every fence in the region. Our volunteer fence pullers pitch in to care for our public lands in partnership with those terrific land managers.

Hundreds of individuals have helped in this way over the past two decades. Some of whom have been on hundreds of fence projects. I’m personally grateful to all of them, and when I pull my boots on to go work on fences, I know that I’m part of something much bigger than me, in so many ways. It is a big, impressive landscape. It is an amazingly long mule deer migration. There are so many people over many years. There is still so much to do.

Thank you to those great young people from Louisiana and their parents, and to EcoTour Adventures. We’re all a part of a great tradition of giving back to the land!

by jhwildlife | May 9, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

“You can’t be unhappy in the middle of a big, beautiful river.” – Jim Harrison

On Sunday, May 6, I had the privilege of participating in my first Nature Mapping Snake River float trip. And what a trip it was!

Along with fellow “bird nerds” Jon Mobeck and Tim Griffith (trip leader/coordinator) and guide Adam “Dutch” Gottschling, I spent two hours of the morning floating the eight-mile stretch of the Snake River between the Wilson bridge and Jackson Hole Vintage Adventure’s Tipi Camp.

Having recently moved to Jackson from the relatively flat plains and forests of the upper Midwest, I have a long way to go before I look up at the grandeur of the Tetons with anything but complete and utter awe. So, had we merely floated for two hours looking only at the river and surrounding mountains, without seeing any wildlife, I personally would have considered my Sunday morning well spent.

That said, we ended up observing over 40 species of birds, mammals and amphibians along the river and in the area immediately surrounding the Tipi Camp. Not bad for the first week of May! (Indeed, I’ve since learned that this is on the high end compared to historic species counts.)

Highlights included 54 American White Pelicans (the largest number ever recorded on one trip), one Swainson’s Hawk, one Merlin, a Greater Yellowlegs and two moose. Though, based on the excitement in the boat, to call the Merlin and Greater Yellowlegs mere highlights is a gross understatement. For good reason too! It turns out only a handful of each species have been spotted by volunteer citizen scientists since the trips began in 2010.

I’d like to say it was beginner’s luck, but I’ve spent enough time appreciating the wild spectacle that is nature to know that to try to claim any credit is silly at best. Besides, who knows what will be seen throughout the rest of this summer? Either way, this trip was an awesome start to what is sure to be an amazing float trip season. Even without such a notable species list, I feel lucky to have been a part of such an experience—to have spent the morning exploring an area of nature that few have the chance to see in a way that even fewer are able to see it.

JHWF partners with AJ DeRosa’s Jackson Hole Vintage Adventures to provide this incredible opportunity to float down the eight-mile stretch of the Snake River between Wilson Bridge and South Park and to collect important data about the various species of mammals, birds and amphibians that use it. Trips take place every Sunday morning from May 6, 2018 through the end of September. Cost is $30 per participant. To learn more, visit the Snake River Float Trip webpage or call the office at 307-739-0968. To sign up for an upcoming trip, contact project coordinator and expert birder Tim Griffith at timgrif396@gmail.com.

Species Counts Along the Snake River

May 6, 2018 8:00 AM – 10:00 AM

Canada Goose 144

Mallard 56

Barrow’s Goldeneye 1

Common Merganser 24

American White Pelican 54

Great Blue Heron 3

Turkey Vulture 4

Osprey 1

Bald Eagle 6

Swainson’s Hawk 1

Red-tailed Hawk 1

Killdeer 3

Spotted Sandpiper 10

Greater Yellowlegs 1

Belted Kingfisher 4

Northern Flicker 4

Merlin 1

Black-billed Magpie 6

American Crow 14

Common Raven 3

Tree Swallow 50

Bank Swallow 5

Cliff Swallow 2

Black-capped Chickadee 7

Ruby-crowned Kinglet 11

Mountain Bluebird 7

American Robin 31

Yellow Warbler 1

Yellow-rumped Warbler (Audubon’s) 5

White-crowned Sparrow 2

Song Sparrow 47

Red-winged Blackbird 11

Brown-headed Cowbird 2

Brewer’s Blackbird 7

Moose 2

Marmot 2

Species Counts at Jackson Hole Vintage Adventure’s Tipi Camp

May 6, 2018 10:15 AM – 10:45 AM

Canada Goose 3

Mallard 3

Green-winged Teal 2

Common Merganser 2

Ruffed Grouse 1

American White Pelican 4

Osprey 2

Killdeer 1

Spotted Sandpiper 3

Downy Woodpecker 1

Common Raven 1

Tree Swallow 1

Black-capped Chickadee 6

Ruby-crowned Kinglet 5

American Robin 5

Yellow Warbler 1

Yellow-rumped Warbler (Audubon’s) 5

Dark-eyed Junco 1

White-crowned Sparrow 1

Song Sparrow 4

Red-winged Blackbird 1

Brewer’s Blackbird 2

Chipmunk 1

Frogs ? (unable to get an exact count)

Greater Yellowlegs!!

by jhwildlife | Apr 30, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Cyclists gather at Bradley-Taggart parking lot for leg two of the Mountain Bluebird Classic.

Jackson Hole Cycling’s unique fundraiser on two wheels this past Saturday, April 28, 2018, brought in over $1,200 for Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation’s (JHWF) Bluebird Nestbox Project.

The “Mountain Bluebird Classic” is an annual spring group ride of the area’s road cyclists. Named for the mountain bluebirds who are busy building nests in cavities during the spring, the cyclists meet at the Home Ranch Visitor Center and ride to the Bradley-Taggart Lake parking lot to meet others who want to ride a shorter 30-mile version of the social ride (from Bradley-Taggart parking lot to Signal Mountain and back).

This year, the National Elk Refuge (NER) was able to open the north pathway early so the cyclists braving the longer 70-mile version of the road ride were able to see many of the nest boxes along the NER’s western border that JHWF installed and have been monitoring since 2003.

Last year, Jackson Hole Cycling’s executive director, Forest Dramis, asked participants to make donations for JHWF’s Nature Mapping Jackson Hole project, which recently added mountain bluebird banding and resighting to its conservation and research efforts. The 2017 ride brought in almost $300 while the 2018 ride raised over $1,200, so far. JH Cycling matched the riders’ donations this year.

Approximately 60 riders took part in this year’s event, which featured “bluebird” skies and unseasonably warm temperatures in the mid-60’s. Two riders even came from out of town for the scenic ride. One cyclist who did the ride last year came back all the way from Minneapolis, Minnesota to tackle the challenging social ride in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP). Another traveled from California to ride with her nephew.

Cyclists regroup at the base of Signal Mountain during the Mountain Bluebird Classic.

The Mountain Bluebird Classic was envisioned eight years ago by avid cyclist and science educator Aaron Nydam who wanted to create an event that captures the spirit of cycling and is inclusive to most all levels.

About Jackson Hole Cycling:

A 501 (c)7 non-profit organization, Jackson Hole Cycling is a group of avid cyclists living in Jackson Hole, Wyo. They provide information and events that help people enjoy the some of the best riding in the country, both road and mountain. (www.jhcycling.org)

Approximately 60 cyclists participated in the 2018 Mountain Bluebird Classic.

by jhwildlife | Apr 20, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

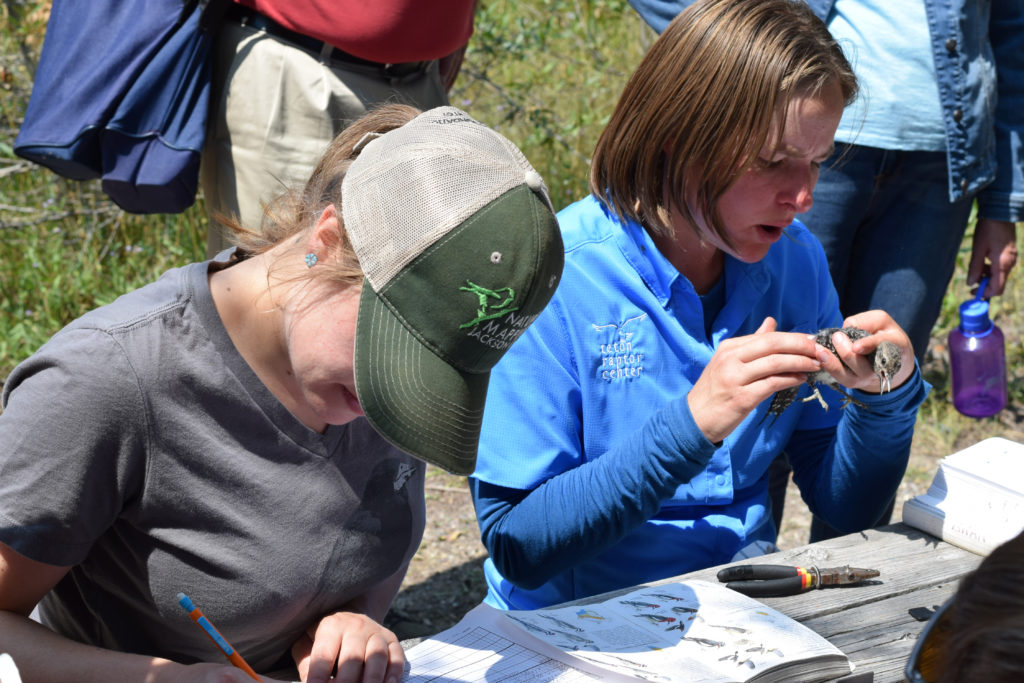

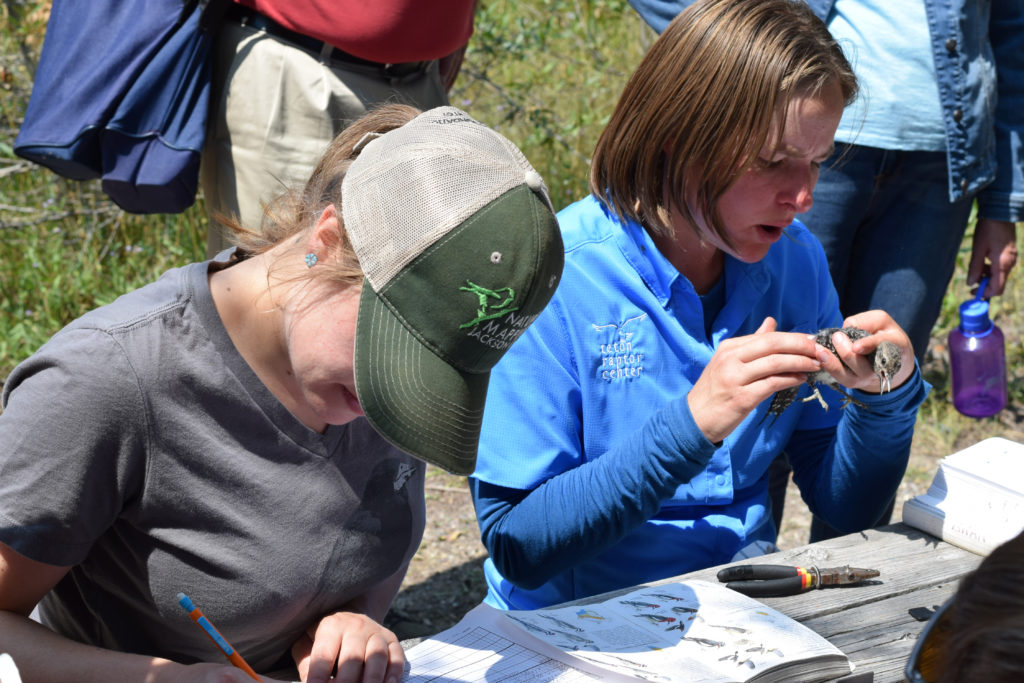

While the saying has had many applications over the years (its first recorded use dates back to the 16th century!), “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” can be taken quite literally when it comes to bird banding. Having a bird in the hand allows researchers to take quantitative measurements and make up-close, detailed observations that, in most other contexts, would be difficult, if not impossible. What’s more, after multiple years of collecting such data, we can start to observe changes and trends within an avian population and, eventually, to make deductions about the health of the ecosystem.

This is largely the goal of the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program. Begun in 1989 by the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), the program is a cooperative effort to collect standardized data on North American landbirds. By increasing understanding of the factors that affect avian populations and their relationships, from a local to a continental scale, ecologists are able to make informed conservation and management decisions. Furthermore, the effectiveness of those decisions will be able to be measured once they have been put into action.

Beginning in June 2018, JHWF staff and volunteers will be leading banding efforts at two MAPS stations in the Jackson area. Both sites were started by the Teton Science School’s Teton Research Institute in 1991 and 2003 and were run by the Teton Raptor Center from 2014-2017. We hope to be able to contribute ongoing data for many years to come!

JHWF Associate Director Kate Gersh (left) records data provided by Teton Raptor Center’s Allison Swan (right) at a banding station in 2017. The two organizations worked closely during a transition year to ensure that the essential program would continue smoothly.

How does MAPS work?

MAPS stations use mist nets, placed at permanent locations within a designated study area, to safely capture birds. Banders extract the birds from the nests and bring them back to a centralized location, where they take various measurements and place a USGS-issued aluminum band on each bird’s leg prior to releasing it. Banding begins around sunrise and the nets are open for six hours during one day of every 10-day period. The season begins in May or early June, depending on latitude (that’s the first week of June for us, in Jackson Hole!) and runs through early August.

So what sort of data does one take from a bird in the hand?

After the species identification and band number (whether it is a newly banded bird or recaptured), the most important data we collect is the age and sex of the bird. Is it a young bird or an adult? Male or female? How exactly we deduce this depends on the species; however, many species of songbirds exhibit sexual dimorphism, meaning the males are visibly different from the females. During the breeding season, this is often most apparent in the bird’s plumage—males have on their “sexy plumage,” to help them attract a mate, while the females’ feathers are more subtle and subdued, to provide camouflage while they are on the nest.

A juvenile American Robin gets banded with a USGS-issued aluminum band with a unique number sequence. This will allow anyone who recaptures the bird in the future to identify it as the same bird!

Alternatively, by blowing on the bird’s abdomen to part the feathers, we can observe less obvious signs. In preparation for incubation, females will develop a bare patch on their breast and abdomen, called a brood patch, which allows efficient heat transfer to keep eggs and nestlings warm. In contrast, a male will develop a cloacal protuberance. A cloaca is the opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts of all vertebrate animals, regardless of sex, with the exception of most mammals. This orifice will swell as the breeding season approaches, allowing us to identify the bird as an adult male. In some cases, detail as subtle as wing or tail length is required to differentiate between males and females!

As with determining a bird’s sex, it is sometimes possible to figure out the age from the bird’s plumage, from the feather coloration and pattern and/or the shape and quality. The specifics depend on each individual species, but the basic idea is that a bird will have plumage distinctions as a juvenile (only recently having left the nest), a young bird still in its first year of life, and as an adult. Some species will retain certain feathers, usually in the wing feathers, that allow more detailed aging assessments to be made. The Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part 1, by Peter Pyle, is an invaluable tool that details information about individual species’ molt patterns and feather characteristics that assist in differentiating between ages and sexes.

As with any rule, there are, of course, exceptions. Generally, though, these are all pretty good indicators. That said, just as it’s good to use multiple clues when identifying a bird or any other animal in the field, so too is it good to use multiple measures when making age and sex determinations in the hand.

Plumage characteristics such as the red patch on the face, tail feather shape, and relative age of the wing feathers help identify this Northern Flicker as an adult male.

Additional measurements taken in the hand:

- Skull ossification – birds have hollow bones and their skulls are no exceptions. The skull develops in two layers, which are ultimately connected by small columns of bone, or “struts.” Upon leaving the nest, only the outer layer is completely formed and the inner layer progressively develops over the subsequent 3-12 months, leaving visible “windows” in the meantime. We are able to monitor this development and potentially use it or its completion to assist in aging the bird.

- Fat – birds’ fat stores are constantly fluctuating. While, during the breeding season, we wouldn’t expect a bird to be carrying much excess fat due to the constant flurry of activity, birds are able to increase their weight 75-100% by storing up fat in preparation for migration.

- Feather characteristics – is the bird actively molting? Is there wear to the flight feathers (wings and tail)? Does the bird have multiple generations of feathers?

- Wing chord – birds’ wings have a natural curvature to them that helps generate lift and allows them to be such effective fliers. We take this unflattened wing length measurement, which is a good indicator of the bird’s size, similar to height in humans.

- Body mass – we weigh the bird using a digital scale, recording the mass to the nearest 0.1 gram.

When able, we aim to take all of these measurements prior to releasing the bird. However, the safety of each and every bird is our priority and we are constantly checking in on the bird’s condition during the banding process. If the bird starts to exhibit signs of stress, we will let it go.

We are thankful for all the time and effort TSS and TRC have invested in continuing this long-term study and are excited to be able to contribute to this impressive data set. To learn more about the MAPS program and importance of long-term research, check out the MAPS project webpage. If you have any additional questions, please feel free to contact Kate Maley, the lead bird bander this season, at katelyn@jhwildlife.org or Kate Gersh at kate@jhwildlife.org. Happy birding!

A Cedar Waxwing perches nearby after being banded and released.

“