by jhwildlife | Nov 4, 2023 | Blog

By Renee Seidler

Sunday November 5th at 2 am is the end of Daylight Saving Time!

Why do we care?

The end of Daylight Saving Time, an age-old practice that is supposed to give us more waking daylight hours, is the number one worst day for wildlife-vehicle collisions in the US. That may seem odd, so let me explain. Animals (and plants!) are amazing creatures with the ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions (albeit there is almost always a time gap to achieve the greatest adjustment due to the ‘learning curve’). Animals move across the landscape to seek food and water and they move away from threats and hazards. They do this adaptively; for example, mule deer migrate in the spring following a ‘green wave’ of maturing plants as snows melt and temperatures warm, only to repeat the migration in reverse in the fall to find the most accessible winter forage such as on wind-swept or south-facing ridges.

How can you avoid getting into a collision with an animal? Knowing this information is a good start!

These animals adjust their departure time and movements each year to find the best forage. Believe it or not, these animals know our commuting hours! When we are driving through that annoying rush-hour to get home, animals avoid crossing the road as best as they can, even when the resources they need are on the other side of the road. In fact, they are so good at avoiding high density traffic that if there is no relief from high traffic levels, animals will opt to never cross the road, i.e., it becomes a barrier. So, we have conditioned animals to our predictable movement patterns to protect their own lives by crossing roads when we are less likely to be driving the road.

Then along comes Daylight Saving and we are not predictable anymore. In the fall, the end of Daylight Saving means we are suddenly driving home on weekdays one hour earlier than usual. Compound that with animals attempting to avoid hunters (which further distracts animals), seek mates during the rut/breeding season (even more distraction), migrate to more favorable climes for the winter, navigate shorter days, and you have quite a perfect storm that can spell out more animals on the road at the ‘wrong time.’ This results in more wildlife-vehicle collisions in the fall, especially starting with the end of Daylight Saving.

How can you avoid getting into a collision with an animal? Knowing this information is a good start! It is proven that being more attentive (e.g., don’t use your phone), driving the speed limit (because it makes it harder to stop before you hit the animal in the road), expecting more critters to cross the road when you see just one, knowing where animals are more likely to cross the road such as at stream crossings or migration routes (look for the road signs!), and helping warn other drivers of hazards by using your flashers when animals are in the road.

by jhwildlife | Jan 22, 2020 | Blog

By Kyle Kissock |

Do slower speeds reduce the chance of a wildlife-vehicle collision?

While the short answer is yes, the longer answer is likely a bit more complicated.

In winter, ungulates like mule deer cluster on the low-elevation buttes around town. Driving the posted speed can help reduce your chances of a collision with an animal.

An article in a recent Jackson Hole News and Guide highlighted the research of biologist Corinna Riginos, who was contracted by the Wyoming Department of Transportation to study the effects of reduced nighttime speed limits on wildlife-vehicle collision (WVC) rates on high-speed roadways.

Riginos’s results indicated that site-specific, nightly speed limit reductions from 70 mph to 55 mph failed to decrease WVCs.

The reason? Despite lower posted nightly speed limits (and in some cases increased enforcement) drivers decreased their average vehicle speeds only 3-5 mph.

This decrease in speed was likely not enough to compensate for the fact that vehicles traveling through “high-speed” study sites were moving relatively fast to begin with.

As the vast majority of WVCs occur at night, drivers involved in collisions likely still “outran” their headlights, a phenomenon that becomes increasingly hard to avoid (even for attentive drivers) as vehicle speeds exceed 35 mph.

However, it’s important to note that this study focused on a specific type of road; high-speed, two lane highways, and does not mean that slower speed limits are ineffective at preventing WVCs.

Rigino’s recent study showed that on high-speed roadways (70-80 mph) nighttime speed limit reductions had little effect to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions

As Riginos points out, research indicates that deer-vehicle collisions in zones with permanent speed limits of 65 mph were over 60% more likely to occur than deer-vehicle collisions in zones with permanent speed limits of 55 mph. In these areas, even a 10 mph decrease made a significant difference.

What about nightly speed limits in Teton County?

Although it does get harder to avoid WVCs at night as you “outrun” your headlights, reducing your vehicle speed still means increased reaction time as a driver.

Currently, ungulates in our valley are residing at low elevations and spending time on or near roadways where travel is easier than wading through the deep winter snow pack.

It’s on these town and county roads, where speed limits are relatively low to begin with, that driver behavior can have an out sized impact on avoiding collisions with wildlife.

For example, reducing your speed from 40 mph 30 mph on Broadway (in the 30 mph posted stretch) likely has more of an impact on collision avoidance than if you were to reduce your speed from 80 mph to 70 mph on, say, Interstate-80.

Moose-Wilson Rd, N. Highway 89 in Grand Teton National Park, and south of town near Rafter J are examples of where recent WVCs have occurred, and where abiding by the speed limit at night (it is the law after all) can truly safe a life.

By modeling good driver behavior, those of us who care deeply about wildlife can set examples for the rest of our community to follow!

by jhwildlife | May 10, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake

On Saturday, April 29, representatives from the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation joined Wyoming Game & Fish Department (WGFD) Wildlife Biologist Gary Fralick to survey winter deer mortality along Highway 89 south of Jackson. None of the participants could have envisioned witnessing an event that brought the poignancy of the wildlife-vehicle issue into vivid focus, but within minutes of starting the survey, they experienced an emotional interaction with one of this winter’s latest casualties.

Fralick led the targeted survey of a half-mile stretch of South Highway 89 from the Snake River Bridge at Von Gontard’s Landing north to Game Creek Road. As a group of six individuals swept through a cottonwood stand on the east side of the highway, they encountered a mule deer doe laying in the underbrush. As the group approached, the deer struggled mightily to flee but couldn’t get to its feet. Its back legs had clearly been broken in a collision with a car. How long it had been suffering there is anyone’s guess, but with the specter of starvation a certainty for an animal with two broken legs, Fralick acted quickly to humanely put the animal out of its misery.

This encounter really struck home for our participants and for Gary himself. All of our organizations recently attended the Wyoming Wildlife and Roadways Summit in Pinedale, which highlighted the biological and engineering considerations in mitigating the impacts of our roads on wildlife and increasing human safety. But this is the side of wildlife vehicle collisions (WVCs) that often goes unseen and is truly tragic. This prime age class doe deer had made it through the difficult winter we had and would likely have survived and helped the population rebound. We also witnessed a side of WVCs that only WGFD wardens and biologists and Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) highway patrol have to participate in and that is the always difficult reality of dispatching an animal, along a busy highway, something that really can never become easy, even for these trained professionals.

Mule deer doe moments after it was put down.

In reality, the life of that deer ended the moment it was struck by a vehicle. As is often the case, an injured animal struggles to its final resting place well off the shoulder of the road, where it may suffer for weeks until it starves to death. The collision may not have even been reported if it hadn’t caused sufficient damage to the vehicle. Studies have shown that up to one-half of deer vehicle collisions go unreported, so the impacts of wildlife-vehicle collisions are actually far greater than the reports on which we base a lot of our decisions.

Survey participants, moved by the power of the moment, mourn the loss of a deer that almost made it through a rough winter.

A few hundred yards from that tragic scene, the group encountered a pair of White-tailed deer carcasses that succumbed under the Flat Creek Bridge, likely after having been struck by vehicles. Those two deer, which died weeks apart in February, incidentally had images captured by a remote-sensing camera that had been placed under the bridge to study the movements of wildlife. Watching the prolonged suffering and eventual death of those deer through time-lapse photography is no easier than witnessing it first hand.

Starting in 2015, several local and regional organizations (Center for Large Landscape Conservation, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, Teton Conservation District and Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative) began working in collaboration with WYDOT to provide pre-construction monitoring of proposed future wildlife crossings along South Highway 89/191 using remote camera sites at locations identified for their importance for connectivity in a future highway redevelopment project that will begin in 2017.

WYDOT is building six large underpasses and many smaller structures to facilitate wildlife movement, reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions, and improve highway safety. The remote cameras are monitoring the proposed locations.

Those underpasses will facilitate safe passage for deer, elk and moose as well as many smaller animals upon completion. The construction of these structures is starting this summer. Studies suggest underpasses are 80%-90% effective at reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions.

The group conducted the targeted survey to collect data that will contribute to WGFD’s knowledge about the mule deer that winter in and around the town of Jackson. Tooth samples were extracted and fibula marrow assessments were conducted on the spot to ascertain age and relative health, or body condition of the animal when it died. The group surveyed a total of one mile – a half-mile on each side of the highway. Within that stretch, 10 carcasses were observed in the ditches and wooded areas along the road underscoring the impacts of this winter on deer throughout the valley, and WVCs on this stretch of South Highway 89.

One of the last carcasses we encountered was a very old age-class doe, with a broken hind leg, wearing an eartag. We’re waiting on the results, but the tag likely came from a study looking at local movements and migrations across our roads. During that study, completed by Teton Science Schools, highway collisions was the number one source of mortality for collared deer. Since the collars have fallen off to allow researchers to collect the data stored within them, it is important that this eartag was retrieved and unsurprising that the individual was killed by a car in this stretch of road years after the study was complete.

Thankfully, construction is about to begin on the first series of underpasses on South Highway 89 and much of the carnage the group encountered on its short survey will be reduced or nearly eliminated in the near future on that stretch of highway.

In 2016, WYDOT, WGFD and local citizens recorded a total of 335 wildlife mortalities on Teton County Highways outside of Grand Teton National Park. This trial winter deer mortality survey illuminated the fact that the actual number of mortalities is likely 25%-50% higher, and it also instilled in the participants a reminder that wildlife deaths caused by vehicles often include a long, painful demise out of our view.

As construction begins on some of the first of our wildlife crossing structures in Jackson Hole, we are also grateful that Teton County is looking at its entire network of roads as it completes a wildlife-roadway master plan with the help of experts at Western Transportation Institute. Many organizations and agencies continue to discuss site-specific solutions to eliminate scenes like those witnessed on the winter deer mortality survey. All options are considered with the knowledge that various mitigation measures may be needed to address some of the complexities of Teton County’s land and roadway system.

by jhwildlife | Jan 30, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Our collective Nature Mapping observations create a long-term dataset of wildlife distribution throughout Jackson Hole. The obvious benefit is that these data provide a more comprehensive view of how wildlife use the valley. The less obvious product of the database is that it includes data that show us how human presence affects wildlife, often in the form of wildlife mortality. The most common reference source for human-caused wildlife mortality is the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation’s Wildlife-Vehicle Collision Database. It contains data derived from WYDOT and Wyoming Game & Fish carcass and crash counts, but also includes Nature Mapping observations from citizens who report roadkill to JHWF at 307-739-0968, or enter their roadkill observations directly via their Nature Mapping account. All of these records eventually are cross-checked to remove duplicates. It is an important resource, adding to our local knowledge, and helping to inform county-wide plans to find solutions that save wildlife and make our highways safer for drivers.

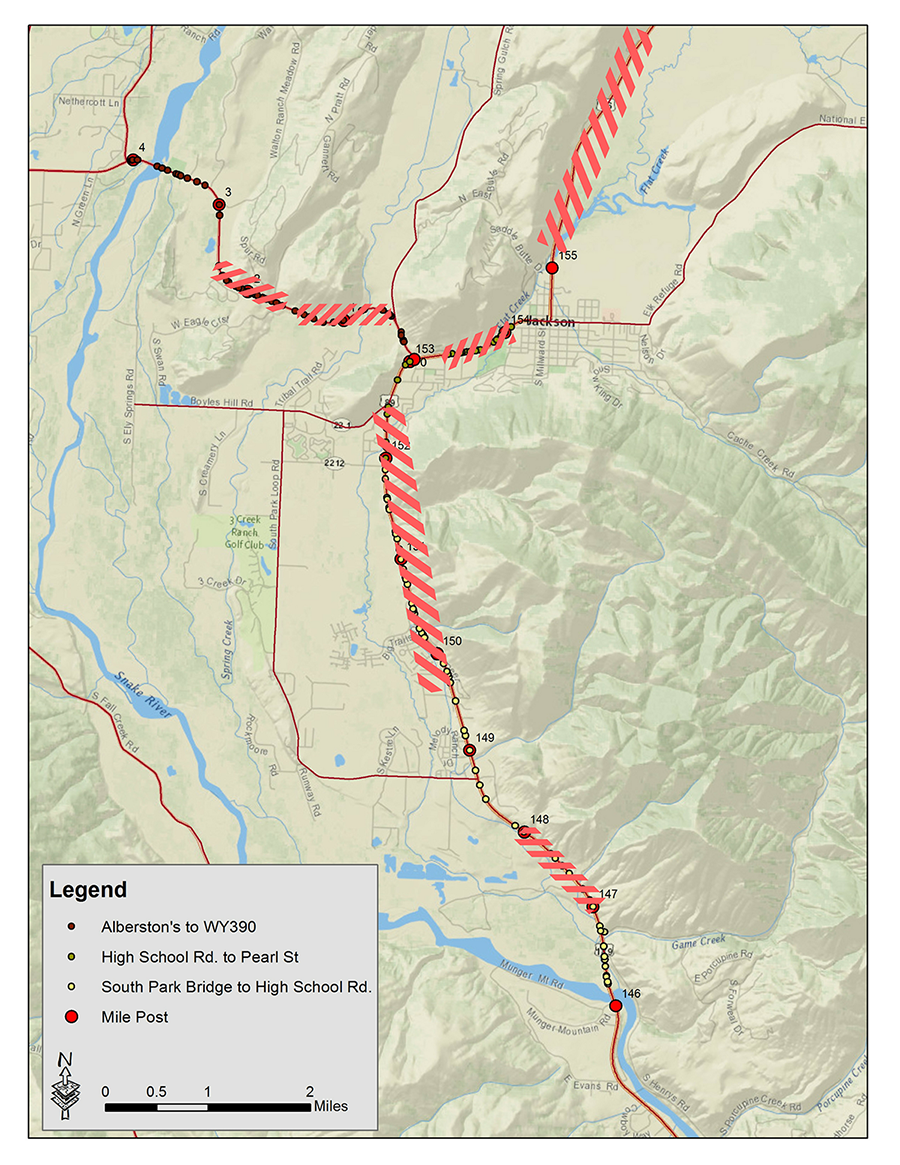

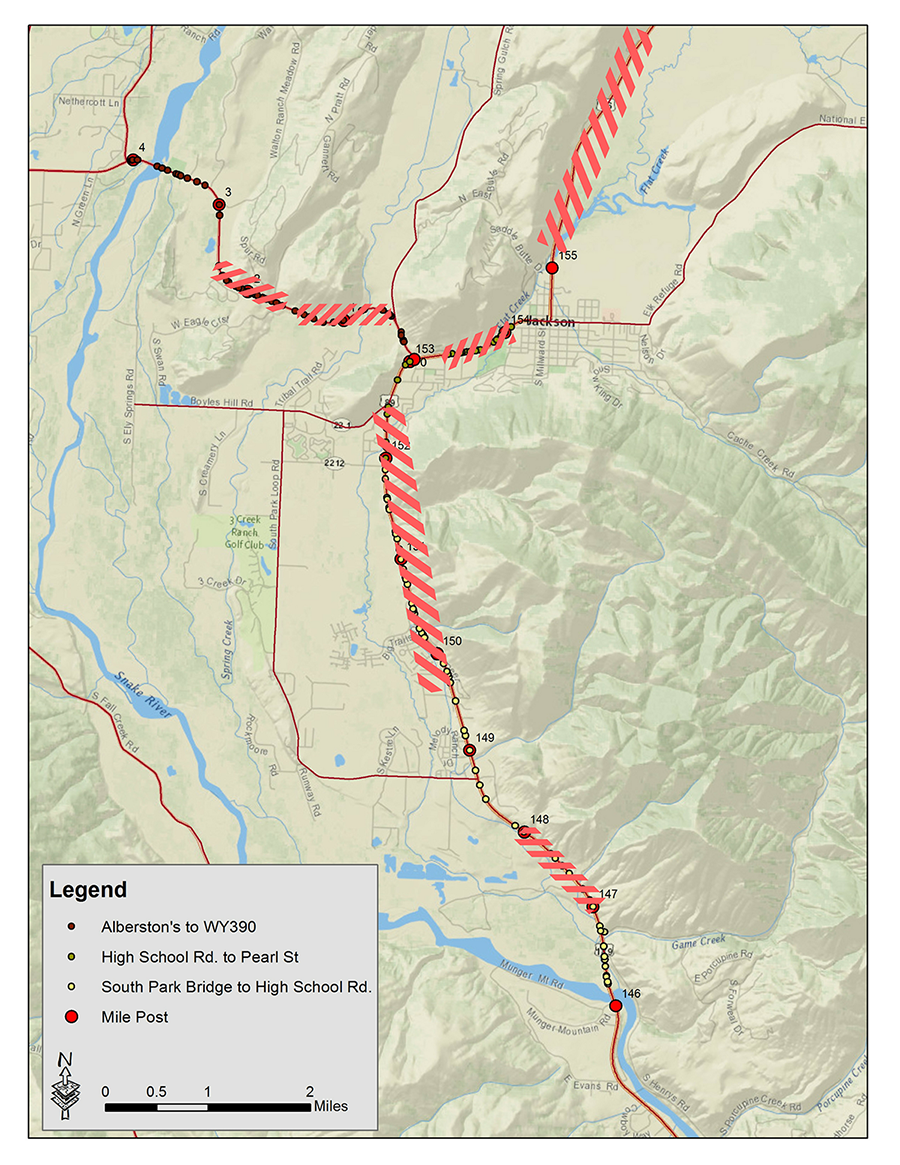

The Wildlife-Vehicle Collision (WVC) Database captured 259 collisions in 2015. Data for the 2015 update was acquired from the following data sources: Wyoming Department of Transportation – Carcass (118), Wyoming Department of Transportation – Crash (70), Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Observation System (33) and Nature Mapping Jackson Hole (28). In total, the WVC database contains 46 total species with mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk and moose being the most prominent species involved in WVCs.

The below map shows where the most frequent collision points are on the local highway network. The highlighted areas had the highest number of collisions from 2013-2015. During this intense winter of 2016-2017, these data have helped us to pinpoint places to add emergency mitigation measures. If you see a dead animal on the side of the highway – small mammals and rodents as well as ungulates – please enter it into the Nature Mapping database, or call us at 307-739-0968 with precise location and time and our staff will enter it. We are likely underestimating the number of animals struck on the highways – certainly for non-ungulates – and our future solutions will depend on our ability to accurately capture what is happening on the roads. Thank you for your help!