by jhwildlife | Jan 27, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake

The Teton County Sheriff’s Office contributed two more variable message signs to a stretch of S HWY 89 as area organizations enacted emergency options to address a challenging winter for wildlife.

We have all seen that this year’s snowpack is making things difficult on wildlife. Mule deer in particular are spending more time in the town and on the roads – wherever they can find easier movement and potential forage. As they join us on the valley floor and move around where we do, the potential for conflict of many kinds increases. An obvious problem arises on our roadways, as high snowbanks both limit driver visibility and make navigation challenging for wildlife. Area organizations and agencies continue to discuss options to address the issue, some having been put in place immediately as short -and long-term strategies to reduce wildlife vehicle collisions are integrated. Here’s an update on the quick-response efforts:

Jackson Hole News & Guide article by Mike Koshmrl (Thursday, January 26)

A small herd of bighorn sheep is frequenting the stretch of N HWY 89 just north of the Dairy Queen near the town limits. Please give them ample space and time to move. Unlike deer and elk, these sheep will obstinately remain on the road.

While a county-wide master plan is in process, an array of short-term mitigation measures have been and will continue to be considered. We are grateful that a good deal of data exists on the relative effectiveness of various measures, which we use to make decisions while also recognizing the constraints of time, resources and feasibility. The planned crossings on South HWY 89 (construction set to begin next spring) will separate animals from the roadway, which data suggests is the most effective way to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions at scale. According to most research, underpasses and overpasses are 80-90% effective at reducing WVCs, while seasonal wildlife alert signage (i.e. variable mobile message signs) is estimated in the 20-25% effective range, making it an effective emergency measure and complimentary piece within a holistic WVC reduction effort. The master plan will likely include a number of mitigation recommendations to include structures, signs and speed limit adjustments to apply the most effective site-specific solutions across the valley.

What can you do now?

- Be alert and drive for the conditions. Most accidents happen at times of low visibility – dawn, dusk, nighttime or in bad weather.

- Watch for electronic warning signs. These signs are put in places where we know animals are or have recently been crossing the road frequently. They’re not just generic warnings – when you see these signs, watch carefully for wildlife.

- When you see wildlife near roadways – slow down immediately. If you see one animal cross the road, it is very likely more are close behind. Animals near the road are not waiting for us to pass by – expect them to do something unexpected, like dash in front of your car.

- In winter, wildlife often use roads to move about – it’s easier than walking through deep snow. But, sometimes they get onto a road and can’t find a quick place to get off. Give them a brake. Be patient and give them time to find a place to get off the road.

- To protect yourself and your passengers, experts advise that you should not swerve off the road to avoid hitting an animal.

- Familiarize yourself with the wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots (located here) and be even more mindful when driving there. Hint: The flashing fixed radar speed limit signs and digital message boards are located in some of these hotspots.

- Get involved with Safe Wildlife Crossings for Jackson Hole to learn about what we can do to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions as a community.

- Contact your elected officials to let them know that reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions is a high priority.

- If you see areas where snowbanks are trapping wildlife on roadways or impeding movement unusually, please don’t hesitate to call us at 307-739-0968. We work with local partners to address these issues if possible.

Additionally, if you are a Nature Mapper, record your observations of wildlife around neighborhoods and roadways. Please use the comments fields to share the activity you observe. The more information we collect about locations and behaviors during winter (all seasons, actually), the better we understand as a community how we are interacting with wildlife, with the goal of living compatibly alongside our wild neighbors.

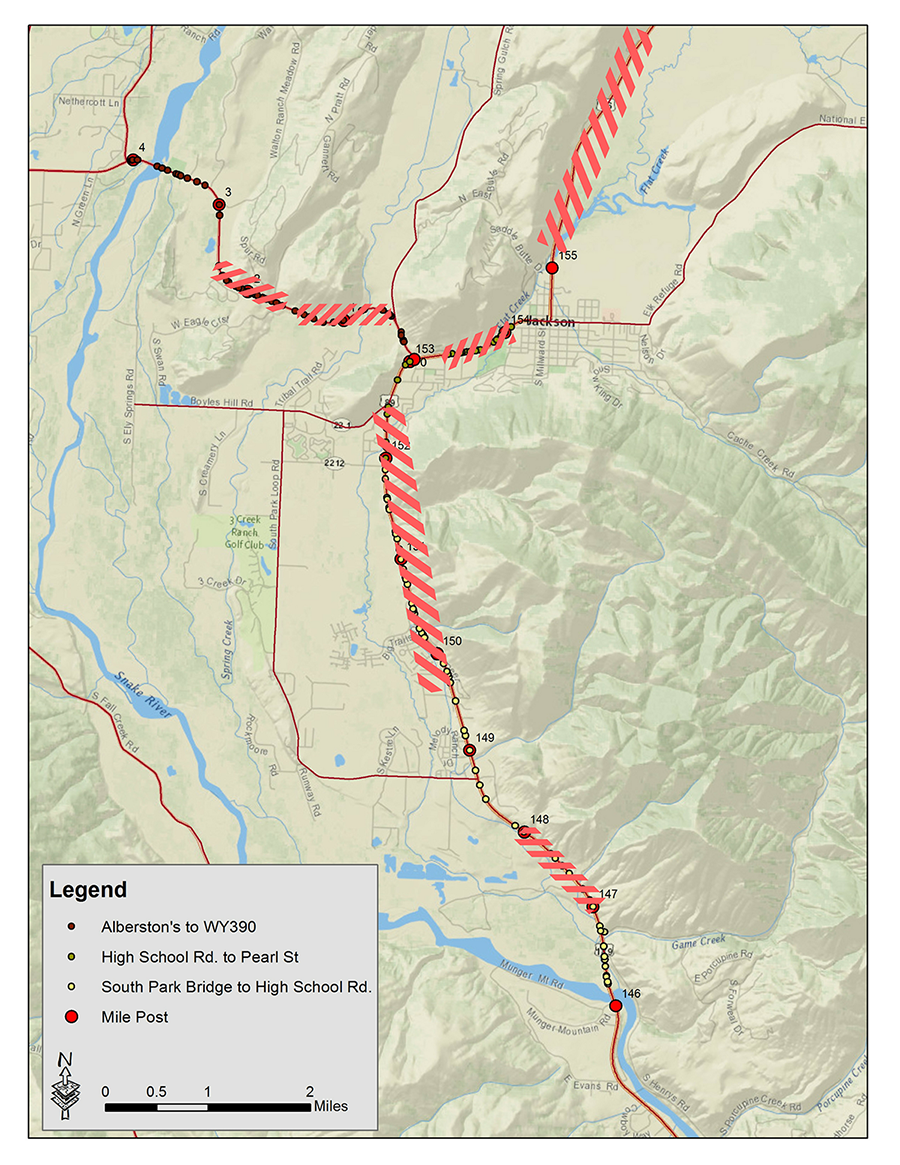

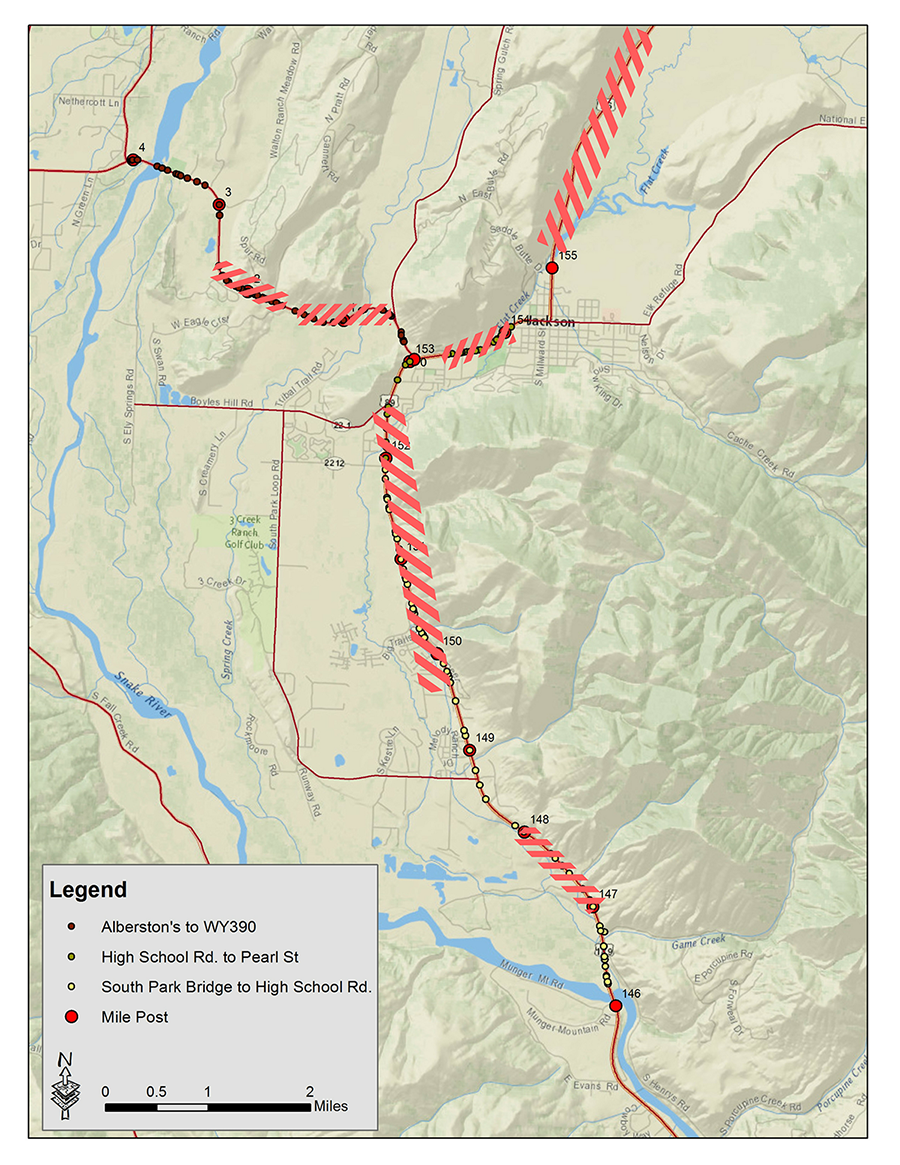

Be especially alert in the areas highlighted on this map!

by jhwildlife | Jan 25, 2017 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

by Frances Clark

Wildlife deals with winter in many ways: some leave the valley, many others stay year-round. They may go underground for the duration; adapt their hunting strategies to deep snow–burrowing below or plunging deep; or just keep on moving until they get lucky. Several members of our Nature Mapping community describe how their favorite animals cope:

Amphibians – Debra Patla, Researcher

The four native amphibian species of Jackson Hole have three strategies to get through our harsh winters.

- Western Toads and Tiger Salamanders go underground, under the frost zone where they are safe from freezing.

- Columbia Spotted Frogs survive in water that does not freeze up, such as in underground springs, spring-fed streams and ponds.

- Boreal Chorus Frogs perform a winter miracle – staying near the ground surface under leaves or in small crevices, their bodies freeze in the coldest times and thaw as it warms up. It is a complicated physiological response to winter, shared by only four other amphibian species in North America.

Rarely, chorus frogs make a surprise appearance in winter, in a basement or garage. This has happened in Teton County! Kind rescuers have discovered that you can help them survive until spring by providing a box with moist, clean vegetation in a cool, dark place.

Beaver: Kari Cieszkiewicz, Winter Naturalist, National Elk Refuge

Beavers are highly industrious rodents that depend on meticulous winter preparation for survival. Before the first significant snowfall, beavers have already winterized their lodges and cached enough food, such as aspen, willow and cottonwood cuttings, for months. Since their teeth continuously grow, beaver must chew regularly on bark to maintain their teeth! These highly productive animals spend the summer months obsessively monitoring their ponds, ensuring that their dams are supporting enough water so ponds do not freeze to the bottom or prohibit access to their lodges.

Short-tailed Weasels (Ermine) – Kari Cieszkiewicz, Winter Naturalist, National Elk Refuge

Short-tailed weasels are highly adapted, masterful carnivores that have a surprisingly commanding presence in winter. Their elongated, slender bodies facilitate easy movement through tunnels in the snow, leading them to unsuspecting mice and voles. When the prey is bountiful, weasels will often store their leftover prey in caches beneath the snow for later feasting! During the winter months their fur changes color from tawny-brown to white, allowing them to be camouflage as they discreetly move across the snow.

Boreal Owl – Susan Marsh – Writer, Naturalist

Among our forest winter residents is a small predator, the Boreal Owl. Their coloration allows them to blend in well when perched in a tree so they are easily missed, but in the spruce-fir forests of winter, they are likely around. They hunt small mammals by ambush, from red-backed tree voles to squirrels. The photo, taken by Jim Hawley in lower Cache Creek, shows a Boreal Owl having just caught a red squirrel.

Boreal Owl Photo credit: Jim Hawly

Interesting adaptations that are especially helpful in winter include the asymmetry of the owl’s ears, found in other owl species as well. One opening is higher on the skull and the other much lower. The positions help the owl tell where a sound is coming from. I tried cocking my head in mimic but was woefully inept at finding a flock of chickadees without my eyes. The owl, on the other hand, can locate prey even under the snow.

Great Gray Owl – Katherine Gura, Field Biologist, Teton Raptor Center

A boreal forest raptor species that is circumpolar, found in the northern reaches of North America, Europe and Asia, Great Gray Owls are well-suited to brave the long, harsh winters in Jackson Hole. Locally, Great Gray Owls generally migrate down in elevation in wintertime and are often seen grouped up in the Snake River bottom where presumably there is less snow and more prey available. Equipped with exceptional hearing abilities, Great Gray Owls hunt primarily by sound and penetrate through as much as two feet of snow to capture rodents that are not visible.

Great Grey Owl Photo Credit: Steve Mattheis

Rough-legged Hawk – Katherine Gura, Field Biologist, Teton Raptor Center

While many species (and people) in Jackson Hole are “snowbirds,” spending summers here and wintering farther south in warmer climes, the Rough-legged Hawk is an exception. In summer months, Rough-legged Hawks breed in the arctic tundra, then migrate south to spend the winter in more “mild” areas in southern Canada and the northern United States. This past year, a Rough-legged Hawk outfitted with a transmitter in northwestern Wyoming migrated north through Alberta and the Northwest territories and finally summered in Nunavut before returning south this fall through Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. In the wintertime, look for these hawks perched on fence lines and power poles in open areas in the Valley.

Rough-legged Hawk Photo Credit: Steve Poole

Coyote: Kari Cieszkiewicz, Winter Naturalist National Elk Refuge

As the sun begins to cast its warming light on the snow-covered meadow, a coyote can be seen making very thoughtful, directed movements. Beneath the snow there is a secret society of critters that live in the subnivean (under snow) zone and the coyote can sense their presence. Using its powerful nose, the coyote sniffs at the ground and precisely locates its prey. With one powerful and swift dive-bomb into the snow head-first, the coyote emerges with its breakfast. Based on what prey is available, coyotes are highly adaptable, adjusting their hunting techniques based on their food source.

With its long legs and large body, moose are adapted to deep snow and long winters. When deep snow is present, moose are surprisingly sedentary, tending to range over very small areas, browsing on shrubs. Surprisingly, moose may move to high elevation conifer forests during the winter, foraging on lichens that hang from conifer boughs. The large body size of moose affords them a favorable surface-to-volume ratio that increases their heat retention, a distinct advantage over smaller ungulates such as deer.

by jhwildlife | Oct 11, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

By Frances Clark, Nature Mapper and Botanist

Hiking under Engelmann spruce trees has been hazardous this fall. Light brown cones, 4-6 inches long and sticky with pitch, pour down amidst harsh chattering from above. I have counted one cone falling every 3-5 seconds, another time I couldn’t keep track of the barrage. Cones landed on my head, bounced and then lay strewn about my feet. Cone storms. What s going on?

Red squirrels are taking advantage of a “mast year.” Last spring, you may remember, prodigious amounts of pollen wafted on the wind. Some of that pollen landed on tiny female cones, which have matured, securing two winged seeds under each scale. Spruce trees are now laden with dangling cones from the top down. This abundance occurs every 2-3 years in spruce. The intervening times are lean.

Red squirrels are taking advantage of a “mast year.” Last spring, you may remember, prodigious amounts of pollen wafted on the wind. Some of that pollen landed on tiny female cones, which have matured, securing two winged seeds under each scale. Spruce trees are now laden with dangling cones from the top down. This abundance occurs every 2-3 years in spruce. The intervening times are lean.

Well adapted to feast and famine, red squirrels form large middens—stores of thousands of cones. They efficiently sample and then harvest trees with the most seed energy per cone and with the greatest cone abundance. Middens lie at the center of the most productive group of trees.

A midden can best be described as several inches of cone scales and cores heaped over mineral soil, forming mounds up to several feet high and wide. The loose surface often has shallow holes in it. In the mineral soil below, there may be a network of tunnels. Squirrels pack several cones, pointed end down, into holes which will be covered eventually by more scales and cores. In this cool and moist environment—a humidor—cones will remain unopened for at least 1-2 seasons until the squirrels retrieve them. When they do, squirrels eat cones like corn-on-the-cob, scattering scales everywhere while consuming the nutritious seeds. It has been calculated that squirrels consume 50-156 cones a day and stash 10s of 1000s in a midden in a good year. No wonder red squirrels are so territorial – chattering loudly at any perceived threat and dashing out to their territorial boundary: they are defending their stash for winter survival.

While cones are preferred, in lean times and in summer, red squirrels will eat other items. Fungi are particularly relished, with parts hung up in trees to dry. They eat buds, fruits, sap, even cambium and phloem, as well as eggs and insects. Small plant parts placed in middens may help train young squirrels for future hoarding. In different years, squirrels may harvest cones of Douglas firs – which have mast years every 4-5 years, or as back up, serotinous cones of lodgepole pine. Lodgepole pine cones are often gathered on top of middens. They do not open even when dry, are too tough for other predators to eat, and seeds remain viable for years. The squirrels don’t need to spend extra energy to bury them.

The other day, walking around Moose Ponds, I heard several red squirrels churring within a stand of battered old spruce and fir trees. Their density indicated good habitat. Tangles of downed limbs and saplings surrounded straight, scaly boles clad in densely needled branches, which intertwined to form a closed, irregular canopy. Engelmann Spruce reach peak production at 150-200 years and provide diverse cover, escape routes, and nesting sites. Old growth trees are excellent for red squirrels.

As red squirrels are active all winter, nesting sites are vital for thermal regulation. Tree squirrels prefer natural cavities, but these are often in short supply so instead squirrels will build a nest of leaves and grass 12 to 60 feet off the ground. Other options include “witches brooms,” an aberrant growth pattern where twigs are unusually dense. They will also burrow into tunnels under their middens for warmth and safety.

Nest sites are located within 100 feet of larders so squirrels can readily defend and retrieve their stores. Circular territories may be 1-2 acres centered around a midden. I nature mapped six squirrels – six territories – on my route past Moose Ponds. While dutiful, I wish now I had taken more time in this rough old patch of forest to see where the middens and nests might be.

Predators come from air or ground. Squirrels may have different calls depending on whether or not a threat is aerial or terrestrial. One study indicates that red squirrels produce a high frequency, short “seet” sound similar to alarm calls of birds. This sound is hard for raptors, such as Goshawk, Great Horned Owl, or Red-tail Hawk , to locate or even hear. A louder bark call is used for overland threats, such as a Pacific (pine) marten (12-20% of marten diet is red squirrels), weasels, or fox. Once alerted, squirrels scramble and hide in dense vegetation.

Between predation and starvation, only 25% of squirrels survive into their second year. Females are in estrus for one day only in early spring. Many males, one dominant in the lead, will give chase and several may succeed in copulation on that one day. In just over a month, the female gives birth to an average of four young which will be independent in another 70 days, by early fall. While mothers may share a territory with daughters, they kick out sons who must then find and defend their own territories by winter. Often the most successful males have ventured the farthest to find a relatively large territory containing an abandoned midden. Midden sites are often used by many generations. In autumn, youngsters and seasoned squirrels are particularly territorial, defending boundaries while gathering cones, which is why they are so vociferous.

Red Squirrels are the most frequently Nature Mapped small mammal with 305 observations over the last seven years. Even so, many of us pass them by – unrecorded – on our hikes. In your next excursions through a conifer forest, listen for chatter. Can you hear differences in their calls? Can you discover a midden nearby? Does a squirrel bound toward you to defend its territory or scurry up a tree or down into a tunnel to escape? Can you find its nest? All these behaviors are fascinating to watch while you may, or may not, log a new Nature Mapping observation.

References:

Animal Diversity Web ADW: Museum of Zoology University of Michigan. Tamiasciurus hudsonicus Red Squirrel. Accessed 10.8.16: http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Tamiasciurus_hudsonicus/

Finley RB. Cone caches and middens of Tamiasciurus in the Rocky Mountain region. Misc. Publ. University of Kansas Museum Natural History. 1969;51: 233–273. https://archive.org/stream/cbarchive_36740_conecachesandmiddensoftamiasci1969/conecachesandmiddensoftamiasci1969 – page/n17/mode/2up

Greene E. Meagher T. 1998. “Red squirrels, Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, produce predator-class specific alarm calls.” Animal Behavior. 1998 Mar; 55(3): 511-8. Accessed through: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9514668

Steele, M.A. 1998. “Tamiasciurus hudsonicus” Mammalian Species 586, pp. 1-9. : published by the American Society of Mammalogists. http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-586-01-0001.pdf

Streubel, D. P. 1968. “Food storage and related behavior in red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) in Interior Alaska.” Masters Thesis. University of Alaska. Source: http://www.arlis.org/docs/vol2/hydropower/APA_DOC_no._3351.pdf

U.S. Forest Service data base: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/animals/mammal/tahu/all.html

by jhwildlife | Aug 8, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

For thirteen years, volunteers have been maintaining a bluebird trail along the boundary of the National Elk Refuge. It is the largest Mountain Bluebird trail in the United States, and it provides essential nesting habitat for these iconic birds, as well as long-term scientific data. This citizen science project is core to the mission of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation: Combining science and the celebration of wildlife.

About Mountain Bluebirds

A male Mountain Bluebird. Photo: Chuck Schneebeck

The brilliant-blue males arrive in Jackson Hole starting in March and begin to select and defend boxes. The pale blue-gray females arrive shortly thereafter and choose a mate based solely on the quality of the nest cavity. They build the nest to fit several eggs—similar in color to Robins’ eggs, but smaller. The males feed the incubating female, often hovering and diving to catch insects such as beetles and grasshoppers.

Phyllis Greene, long-time monitor and past project coordinator, has observed: “They lay one egg a day, but the eggs hatch out all at once. It’s fun to watch. I have seen the chicks peck out through the shell. When they hatch, they are the size of your pinky and nude. First thing, they have their mouths open for food. They are adorable.” The chicks develop pin feathers and then “become more of a bird.” The monitors observe the nestlings from afar after the first 12-14 days so that the birds won’t fledge prematurely. Then after about 3 weeks total, ”They fly off. ‘Ok, good-bye.’ It’s sad. They are so gorgeous.” Adult males depart Jackson in early August. The females and young leave a little later. These birds, considerably smaller than a robin, migrate as far south as Mexico and Central America.

Nesting success is tenuous. While Tree Swallows arrive two weeks later than Mountain Bluebirds – after many bluebirds have claimed boxes – they often out-compete the bluebirds when they would otherwise attempt a second brood. Tree Swallows are a beautiful, native bird, so their presence is enjoyed as well, despite the challenge to bluebirds. Future nestbox plans aim to accommodate the greatest number of both species. Also, according to project coordinator Tim Griffith, weasels and raccoons have been known to raid the nests, which lowers the success rate. Overall, the North American Breeding Bird Survey indicates Mountain Bluebird populations declined by about 26% between 1966 and 2014. We will continue to analyze our data to see how the birds have been faring here in Jackson Hole.

The Origin of the Mountain Bluebird Nestbox Trail Project

Female Mountain Bluebird. Photo: Chuck Schneebeck

Chuck Schneebeck started the project in 2003. He read a study about the loss of aspens due to intensive ungulate grazing on the National Elk Refuge (NER). Bluebirds are cavity nesters, naturally using holes in old aspen trees carved out by woodpeckers or formed by a rotted tree limb. On the Refuge, the loss of standing aspens due to elk browsing meant the loss of nesting habitat. In an informal survey, “We found only one nest from Flat Creek to the Gros Ventre River, in an electrical box by the visitor center.” Chuck realized that to mitigate the impact of grazing, “We could build cavities: nest boxes.” Having worked on a bluebird trail for the National Audubon Society in Dubois, WY, he knew how to start.

From the beginning, Chuck engaged the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and community. The Foundation provided funds for the materials and Chuck donated his labor. With the cooperation of NER, he and others set up 105 boxes 100 yards apart placed five or more feet high along the western boundary fence. Citizen science volunteers were assigned about 15 boxes each, which requires a mile walk and about an hour a week to monitor. They start surveying in April and continue into August. Monitors also help clean out and repair the boxes in the off-season.

The Monitoring Process

Kate Gersh, JHWF Associate Director and project monitor

Phyllis Greene’s approach is, “We talk to the box and tap first, saying ‘Hi, coming to see you. How you are doing?’ Then we open the lid and look in. Mom just looks up and blinks her yes and says ‘how do you do?’ We close the lid then record what we saw. They don’t mind the monitoring and we never touch them.“

Phyllis goes on to say that the monitors become “very maternal or paternal. We want to give the birds a chance because they are almost extinct out here.”

While monitors are surveying along the road, people often stop and ask what they are doing. “We explain the project and they respond, ‘That’s great!’ People get excited and appreciate that someone is doing something for these little birds,” recalls Phyllis.

How do volunteers feel about the project?

For Chuck Schneebeck – project founder – while the project does not supply all the complexity that the bluebirds need, “We are doing what we can. The fundamental part is that we have cavities and bluebirds have been using them for a long period of time. So there are lots of birds now.”

Phyllis Greene, who took over the project from Chuck: “The important thing is for the birds to have an opportunity to have a nest, to get out of the weather and survive. We want to make sure they have a chance. Originally they were almost extinct in lots of places throughout the US, not only here. Anytime we can help wildlife sustain itself and still be independent is a great idea.”

Jon Mobeck, Executive Director of JHWF says the project fits the mission of the organization. “This is a visible way to demonstrate how to mitigate our impacts of development on wildlife. It is a perfect example of the community coming together and helping out this beautiful species. It combines science and the celebration of wildlife.” And more personally, Jon had no experience with birds prior to taking on 12 boxes with the JHWF staff. He is becoming a bird watcher. “Now I have a whole new way of observing the environment. It has been eye opening and ear opening. A tremendous gift.”

Tim Griffith, our new project coordinator, has been engaged with Eastern Bluebird trails for years in Indiana before moving here a year ago: “This is the largest registered Mountain Bluebird Trail in the continental U.S. Mountain Bluebirds are crashing throughout the region. With 13 years of data, we can know more about the population and be responsive to changes in trends upward instead of downward. The more we know about this iconic western species the more we can save and increase their populations here and elsewhere.”

Natalie Fath, Volunteer Coordinator and Visitor Services Manager for the National Elk Refuge: “The ongoing collaboration with the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation on the Mountain Bluebird Nestbox Trail Project is essential to ensuring that monitoring, box maintenance, and reporting occurs. The NER is not only supportive of the collaboration, but also depends entirely on volunteer citizen scientists to give this project life due to Refuge full-time staffing limitations. Without volunteers, this project would not exist.”

Future Plans

A male bluebird watches as a monitor approaches. Nestlings are getting ready to fledge.

Next year, Tim plans to start banding birds to see how many return, and to which boxes. Eagle Scouts are ready to repair and build more boxes to place at other areas in the Refuge. Also, we will digitize the years of data for submission into our Nature Mapping database and Cornell’s national NestWatch system.

Jon Mobeck sums it up, “The Nature Mapping Bluebird Nestbox Project is a great way to introduce citizen science to the community. It is a visible and fun project. We welcome new volunteers!”

We thank the ongoing core project volunteers who are still in the valley:

Chuck Schneebeck, Ed Henze, Bert Raynes, Paul Anthony, Phyllis and Joe Greene, Loretta Scott, Larry Kummer, Julianne O’Donoghue, Gretchen Plender, Shelly Sundgren and Dave Lucas; Jon Mobeck, Kate Gersh, Christine Mychajliw, Tim Griffith.

Additional thanks to Jackson Lumber, which often donates cedar wood for the boxes.

Contact Tim Griffith to help out: Timgrif396@gmail.com.

References:

by jhwildlife | Aug 3, 2016 | Blog

Hello, moose!

There was rustling in the tall grass aside a lazy stream. A Great Blue Heron had led me here, after I had failed in a few attempts to get close to the elegant bird. I had followed its flight from take-off to landing three times now, walking quickly and quietly along the banks of these Snake River backwaters. On this third episode of the chase, the heron swooped low and banked left around some dense vegetation and, for the first time in an hour, left my view. Undeterred, I walked through the brush in the direction of the heron’s flight and zeroed in on its likely landing area. I thought I was close when I saw the rustling of the stream-side grasses. The rustling rose to what sounded like ripping and tearing, and from the vegetation emerged a moose. A clever trick by the heron to lead me to this distraction. My curious, observing eyes had found a new subject. Heron exits stage. Moose steps up to her mark.

Throughout all of this, I hadn’t seen any other people. These side channels are quiet, save for the low hush of the Snake River’s current murmuring beyond. The interactions with wildlife here are intimate. This moose and I were alone in this great theater. I watched her turn her head repeatedly to tear chutes of grass. As the early afternoon sun intensified, she slowly – very slowly – took a step into the water, and then another. And then a long pause as she stood in water that reached nearly to her belly. I could feel her demeanor change as she entered the water – its cooling effect clearly relaxing her and enticing me.

The moose enjoys cooling off on a hot, summer day.

What a joy to observe all of this. After a good while, she moved farther into the backwater and I moved from observation to reflection. What am I learning? What is she sharing with me?

I had come to this place to learn more about birds. I had my bird guide with me and a field notebook. I’ve become familiar with perhaps a few dozen birds by sight and sound this summer, and once that gate was opened, the search has become relentless and exciting. Every day seems to reveal a new bird, and what a gift that is. It’s strange to think that all these birds have always been there, but I never really noticed them.

Before the heron, and long before the moose on this day, I had identified the American Goldfinch for the first time. To those who know this common bird, it’s a fairly ordinary occurrence, however delightful. It’s such an exceptionally beautiful bird to observe. I first saw the goldfinch through my binoculars as it perched in a cottonwood tree. Glancing back and forth between my bird guide and the bird in the tree, I couldn’t identify it with

Always a thrill to see the Great Blue Heron.

certainty. But then it flew! And what a distinctive flight it is! Singing as it flies upward, then pinning its wings back for a joyous little dive. Up and down. Up and down, reminiscent of the motion we repeat when we stick our hand outside a car window and ride the air waves. I’ve since been told by an expert birder that the American Goldfinch is the “rollercoaster bird.” Perfect. What an awesome bird!

As this new world of birds has opened to me, so has my desire to record what I observe. I go back to the same place at least weekly – more often if I could – and so far I’ve never failed to see something new. I enter all of my observations into the Nature Mapping Jackson Hole database. By doing so, I contribute to our collective experience of living in this wild place. The data can be useful to local species knowledge and even to planning efforts, but maybe the greater thrill is to feel a part of a community that connects with wildlife in this meaningful way. Once I’ve committed to recording what I observe, the wonderful interactions and beautiful experiences seem to multiply many times. We share with wildlife. We share with each other. This sharing might be the essence of living in this remarkable place.

An American Goldfinch in joyful flight. A gift to us!

This valley is filled with some of the world’s finest biologists, birders and experts of every ecological field. While I’m not among these talented folks, my love for wildlife and gratitude for the beauty of a place like Jackson Hole is something that I want to share. Many people feel as I do, and Nature Mapping Jackson Hole is one place where we come together, around a shared appreciation for a place and the wild things we love.

Written by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, and enthusiastic new Nature Mapper