by jhwildlife | May 10, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake

On Saturday, April 29, representatives from the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation joined Wyoming Game & Fish Department (WGFD) Wildlife Biologist Gary Fralick to survey winter deer mortality along Highway 89 south of Jackson. None of the participants could have envisioned witnessing an event that brought the poignancy of the wildlife-vehicle issue into vivid focus, but within minutes of starting the survey, they experienced an emotional interaction with one of this winter’s latest casualties.

Fralick led the targeted survey of a half-mile stretch of South Highway 89 from the Snake River Bridge at Von Gontard’s Landing north to Game Creek Road. As a group of six individuals swept through a cottonwood stand on the east side of the highway, they encountered a mule deer doe laying in the underbrush. As the group approached, the deer struggled mightily to flee but couldn’t get to its feet. Its back legs had clearly been broken in a collision with a car. How long it had been suffering there is anyone’s guess, but with the specter of starvation a certainty for an animal with two broken legs, Fralick acted quickly to humanely put the animal out of its misery.

This encounter really struck home for our participants and for Gary himself. All of our organizations recently attended the Wyoming Wildlife and Roadways Summit in Pinedale, which highlighted the biological and engineering considerations in mitigating the impacts of our roads on wildlife and increasing human safety. But this is the side of wildlife vehicle collisions (WVCs) that often goes unseen and is truly tragic. This prime age class doe deer had made it through the difficult winter we had and would likely have survived and helped the population rebound. We also witnessed a side of WVCs that only WGFD wardens and biologists and Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) highway patrol have to participate in and that is the always difficult reality of dispatching an animal, along a busy highway, something that really can never become easy, even for these trained professionals.

Mule deer doe moments after it was put down.

In reality, the life of that deer ended the moment it was struck by a vehicle. As is often the case, an injured animal struggles to its final resting place well off the shoulder of the road, where it may suffer for weeks until it starves to death. The collision may not have even been reported if it hadn’t caused sufficient damage to the vehicle. Studies have shown that up to one-half of deer vehicle collisions go unreported, so the impacts of wildlife-vehicle collisions are actually far greater than the reports on which we base a lot of our decisions.

Survey participants, moved by the power of the moment, mourn the loss of a deer that almost made it through a rough winter.

A few hundred yards from that tragic scene, the group encountered a pair of White-tailed deer carcasses that succumbed under the Flat Creek Bridge, likely after having been struck by vehicles. Those two deer, which died weeks apart in February, incidentally had images captured by a remote-sensing camera that had been placed under the bridge to study the movements of wildlife. Watching the prolonged suffering and eventual death of those deer through time-lapse photography is no easier than witnessing it first hand.

Starting in 2015, several local and regional organizations (Center for Large Landscape Conservation, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, Teton Conservation District and Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative) began working in collaboration with WYDOT to provide pre-construction monitoring of proposed future wildlife crossings along South Highway 89/191 using remote camera sites at locations identified for their importance for connectivity in a future highway redevelopment project that will begin in 2017.

WYDOT is building six large underpasses and many smaller structures to facilitate wildlife movement, reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions, and improve highway safety. The remote cameras are monitoring the proposed locations.

Those underpasses will facilitate safe passage for deer, elk and moose as well as many smaller animals upon completion. The construction of these structures is starting this summer. Studies suggest underpasses are 80%-90% effective at reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions.

The group conducted the targeted survey to collect data that will contribute to WGFD’s knowledge about the mule deer that winter in and around the town of Jackson. Tooth samples were extracted and fibula marrow assessments were conducted on the spot to ascertain age and relative health, or body condition of the animal when it died. The group surveyed a total of one mile – a half-mile on each side of the highway. Within that stretch, 10 carcasses were observed in the ditches and wooded areas along the road underscoring the impacts of this winter on deer throughout the valley, and WVCs on this stretch of South Highway 89.

One of the last carcasses we encountered was a very old age-class doe, with a broken hind leg, wearing an eartag. We’re waiting on the results, but the tag likely came from a study looking at local movements and migrations across our roads. During that study, completed by Teton Science Schools, highway collisions was the number one source of mortality for collared deer. Since the collars have fallen off to allow researchers to collect the data stored within them, it is important that this eartag was retrieved and unsurprising that the individual was killed by a car in this stretch of road years after the study was complete.

Thankfully, construction is about to begin on the first series of underpasses on South Highway 89 and much of the carnage the group encountered on its short survey will be reduced or nearly eliminated in the near future on that stretch of highway.

In 2016, WYDOT, WGFD and local citizens recorded a total of 335 wildlife mortalities on Teton County Highways outside of Grand Teton National Park. This trial winter deer mortality survey illuminated the fact that the actual number of mortalities is likely 25%-50% higher, and it also instilled in the participants a reminder that wildlife deaths caused by vehicles often include a long, painful demise out of our view.

As construction begins on some of the first of our wildlife crossing structures in Jackson Hole, we are also grateful that Teton County is looking at its entire network of roads as it completes a wildlife-roadway master plan with the help of experts at Western Transportation Institute. Many organizations and agencies continue to discuss site-specific solutions to eliminate scenes like those witnessed on the winter deer mortality survey. All options are considered with the knowledge that various mitigation measures may be needed to address some of the complexities of Teton County’s land and roadway system.

by jhwildlife | May 2, 2017 | Blog, Wildlife Friendlier Landscapes

The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation has announced dates for its public fence projects in 2017 following its winter and spring of project coordination and site reconnaissance. The Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program reduces dangerous and challenging barriers to wildlife movement.

Public projects offer volunteers the opportunity to contribute to the removal or modification of fences that pose avoidable threats to wildlife while fragmenting vital habitat. JHWF and its “Fence Team” leaders also work on a number of private projects with landowners throughout the summer toward the same end.

Public fence projects typically occur on Saturdays usually from 9am – 2pm with a lunch break. On some projects, half-day “shifts” are available. While listed dates are subject to change or cancellation due to weather and other conditions, JHWF encourages volunteers to save the dates in order to ensure that all can participate as their schedule allows.

JHWF will require an RSVP from each volunteer in advance to ensure that we have the ideal number of volunteers for each project. Interested volunteers receive an email invitation and RSVP request about two weeks prior to the project date with the description, details and other logistics outlined. Please email jhwffencepull@gmail.com or info@jhwildlife.org if you are not currently receiving fence project updates and would like to, or if you have questions about volunteering.

Wildlife Friendlier Fencing Public Project Dates 2017:

- June 3

- June 17

- July 15

- July 29

- August 12

- August 26

- September 16

- September 30 – Public Lands Day

Photo credits: Sava Malachowski

by jhwildlife | Mar 7, 2017 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Earle Layser spots moose tracks in West Jackson

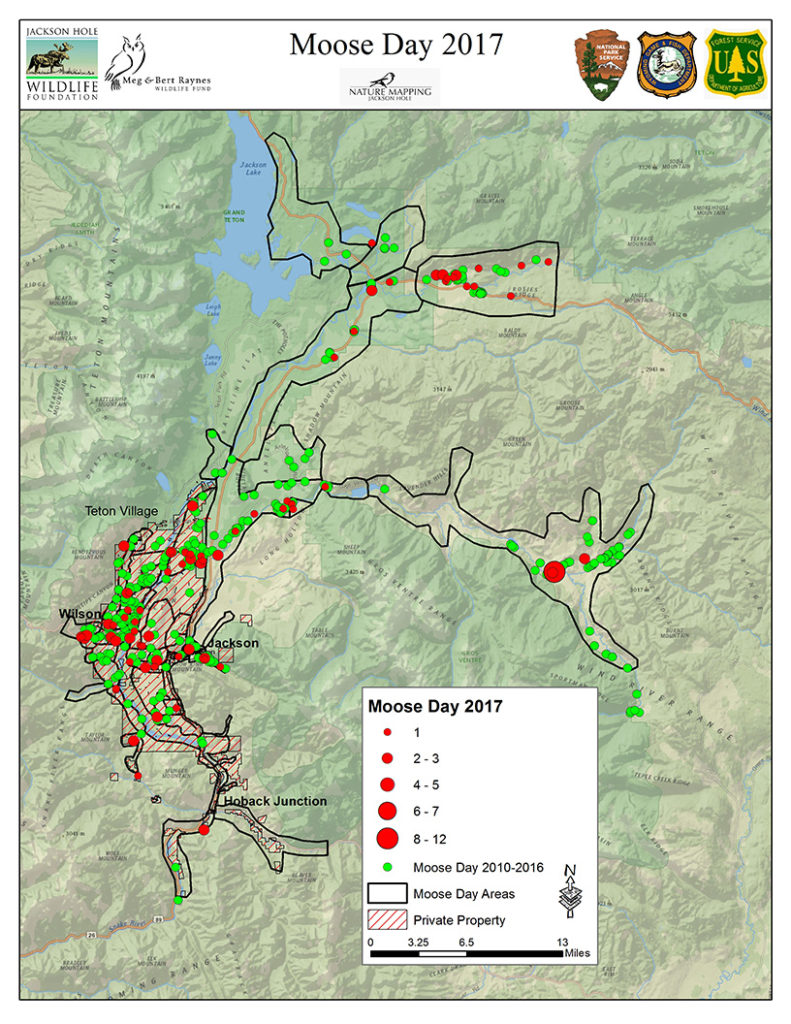

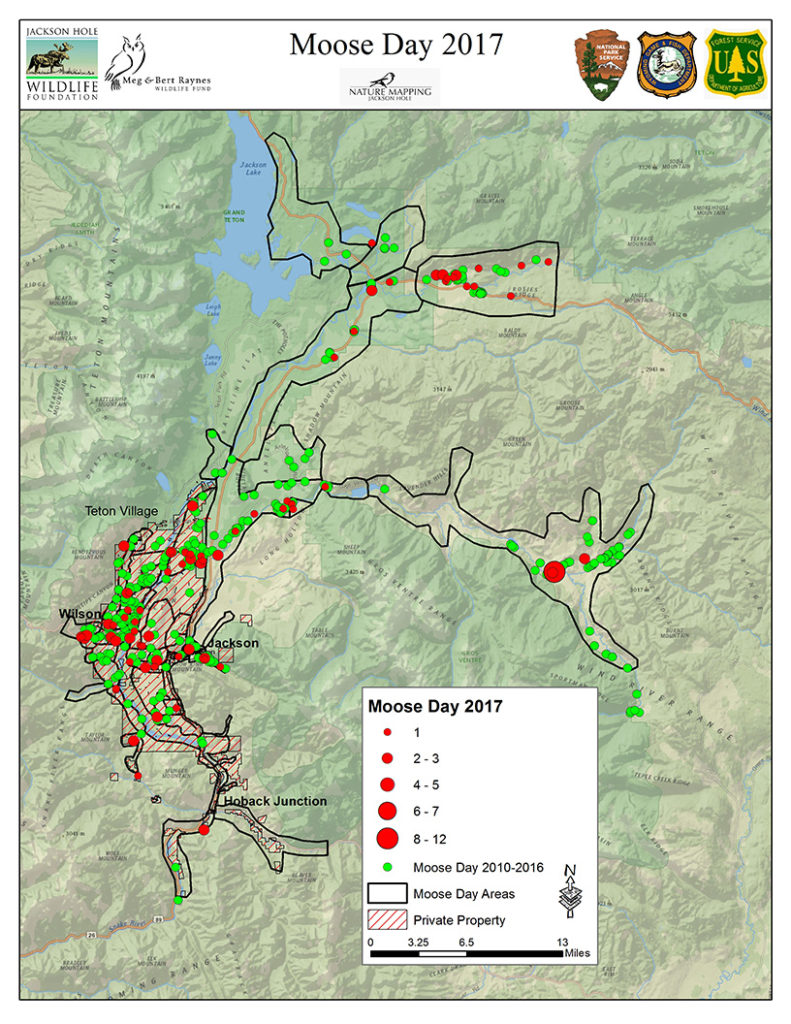

Moose Day 2017 set a record for community participation and for the number of moose counted. We extend our thanks to the Nature Mappers and new recruits as well as, biologists from Wyoming Game & Fish Department, Grand Teton National Park and U.S. Forest Service. All volunteered their time from 7 a.m. to 12 noon on Saturday, February 25.

This year, a total of 33 teams, comprising 83 volunteers counted 166 moose, contributing over 290 hours time.

This exceeds our previous record of 124 moose in 2011, and the 99 moose seen last year. Volunteer numbers are well over our 65 person average. In 2016, we had 73 participants helping with the count. This was our 9th annual Moose Day.

Volunteers snowmobiled, snowshoed, drove, walked and most of all, climbed up snow banks to scout moose! Many were rewarded by seeing moose — in some cases many! Successful surveyors often had local tips or tracked fresh moose sign to find hidden individuals. In other cases, neighborhood teams were disappointed to not see the moose that was “there yesterday” and saw no moose at all. However, zero (0) moose is important data as well. And, it is clear that moose move!

A moose feeding by Randy Reedy

Where were the moose this year? It appears they were attracted to low-lying willow wetlands, such as Buffalo Fork Valley, along the Gros Ventre River and in Wilson. For instance, Kerry Murphy and his U.S. Forest Service team were able to survey the Gros Ventre all the way east to Darwin Ranch. Along this route, often with extensive willow stands, they surveyed 57 moose! Much closer to civilization, moose were seen browsing on exotic shrubs in Jackson or loafing in the shelter of buildings. In a few spots, moose were even congregating close to horses.

Where were moose missing? Often in areas of extremely deep snow, such as the northern stretches of Grand Teton National Park and at the base of the mountains along Fish and Fall Creek Roads. Other wide open areas had little browse for the amount of effort it would take to reach it. Fortunately, most reports indicate moose were in good condition.

Other critters like Bald Eagles were mapped, too. Photo by Alice Cornell

Whether Nature Mappers saw moose or not, they reported a good time. Many observed (and mapped) other critters as well: wolf, coyote, Trumpeter Swans, otter, beaver, Bald Eagles, elk, Red Crossbills, a dipper and other birds. Teams of friends and strangers enjoyed each other’s company for the morning, and over 30 volunteers showed up at E.Leaven for lunch to share their stories. Moose Day is very much a community event!

30 moose mappers recounting the morning’s count at E. Leaven. Photo by Frances Clark

Moose munching by Mary Lohuis

Moose Day is important because we survey moose on private lands, where public-land biologists rarely go. We thank the Snake River Ranch, Snake River Sporting Club, Jackson Holf Golf & Tennis, and Trail Creek Ranch as well as, homeowner associations and individuals for granting permission for us to survey their private property. Without their support we would not have counted so many moose!

Next, Paul Hood and Aly Courtemanch will analyze the data and produce a formal 2017 Moose Day report. This report will enable biologists to determine trends in moose populations and planners to understand where moose roam and rest.

Again, many many thanks to the Nature Mapping Jackson Hole community for caring about our Teton County moose!

Frances Clark

Moose Day Coordinator

Note: Moose By The River photo by Alice Cornell

by jhwildlife | Feb 27, 2017 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

by Susan Marsh

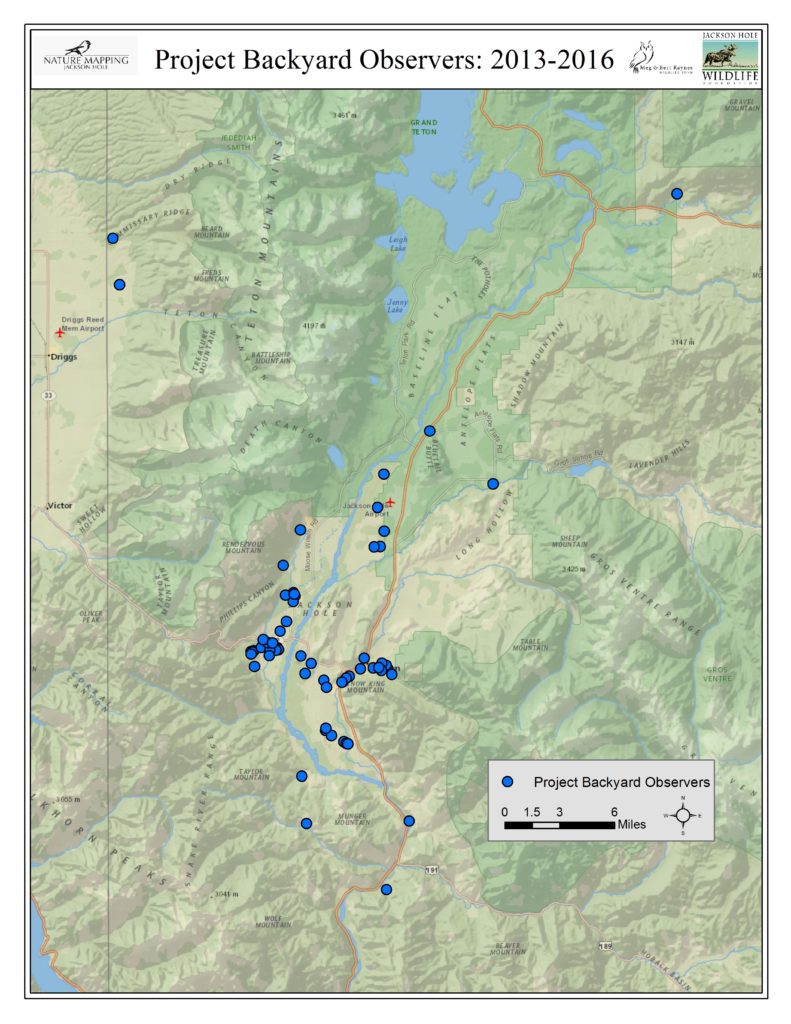

When Nature Mapping Jackson Hole began in 2009, Project Backyard (PBY) was born. It was the first systematic observation protocol developed for Nature Mapping Jackson Hole, meant to augment the casual observations that people recorded while driving or wandering along the mountain trails. What’s the difference between PBY and casual observations, and why does it matter?

A good example may be taken from our first attempt at counting moose on a single day for Nature Mapping Jackson Hole, prior to the start of the organized Moose Day, for which observers are assigned specific areas. On that first count we had lots of observations, but many of them turned out to be the same dozen moose in the Antelope Flats area. It became clear that casual observations could only give so much accuracy on a single day.

What was the best way to achieve a more systematic approach that would be easy for people to work with? Asking homeowners to record what they saw from their backyards seemed like the answer.

Participants in PBY make weekly observations, recording the maximum number of each species seen during a single week. No need to use a GPS unit – anyone participating in the project enters the coordinates for their location once, and they come up automatically each time. You can do it less frequently than weekly, and you don’t have to sit watching the bird feeder all day – just note what you see.

The response has been remarkable. Over 19,140 observations have been made in Project Backyard. These observations are particularly valuable as they provide information about the wildlife living in, or moving through, our neighborhoods and agricultural lands. While the federal agencies and Wyoming Game & Fish Department conduct wildlife counts on public land, they are often geared toward particular species, such as the classification count each February on the National Elk Refuge. Private lands are not included in agency counts since access is not always granted. But if you live there, you can provide valuable insights. It is through private citizen observations that we know about where small elk herds are moving as they increasingly stay the winter in the Wilson area and elsewhere on the valley floor – especially in this high-snow year. It is through citizen observations that we know the winter of 2016-2017 has been a low year for many species of songbirds that are often seen in higher numbers at feeders.

We collect this information not just for our edification. Nature Mapping Jackson Hole receives requests from the county, environmental consulting companies, researchers, non-governmental organizations and land developers, asking for information about what wildlife species might be affected by upcoming plans. Any data that a private firm or individual receives also go to the Teton County Planning & Development Department. Our data help make good decisions for wildlife in the valley.

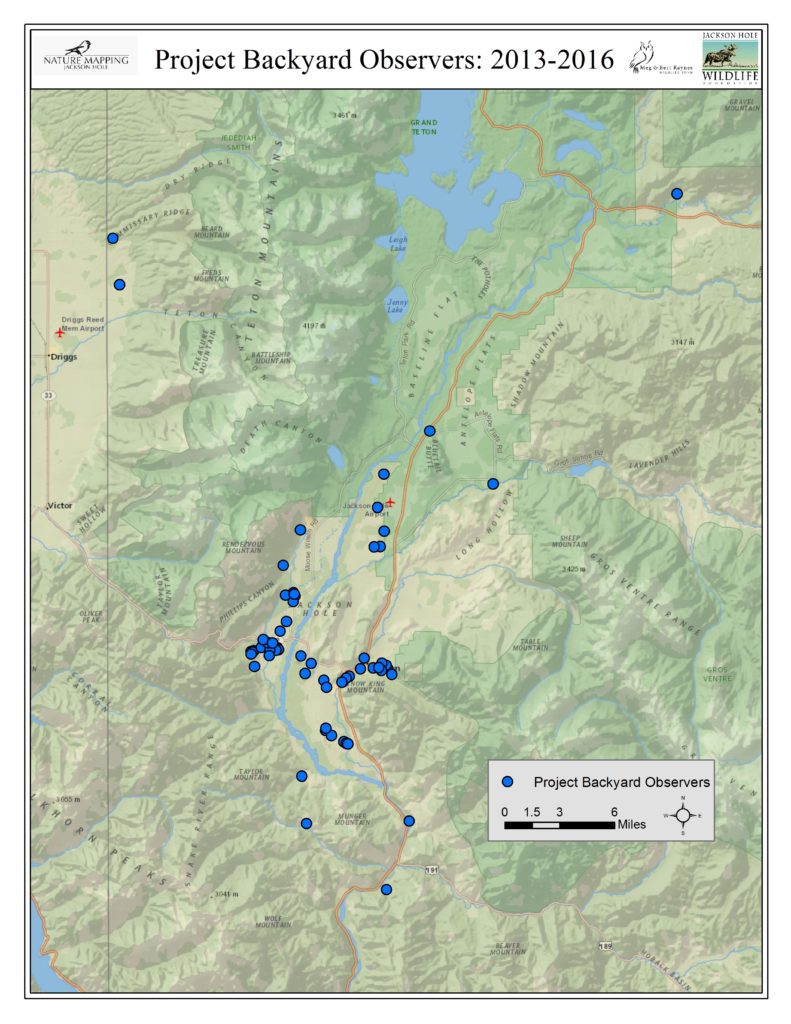

Some PBY observers have been providing information since the inception of the project. Others are welcome additions to the group, adding data from new locations that help give us a broader picture of Teton County wildlife. Many PBY observers are located in a few places — unsurprisingly, those areas where people live: Jackson, Wilson, Rafter J and along WY 22 and HWY 390. Others are located in Alta, Buffalo Valley and scattered from Munger Mountain to Blacktail Butte. It would be wonderful to fill some gaps where observations are not being made, including Moran, Spring Gulch and both Gros Ventre Buttes, the south end of the county, Hoback Junction, Kelly and the Shadow Mountain area. Populations are sparse in some of these spots, so there aren’t many backyards from which to observe. But slowly, we are building a valuable database using citizen science, thanks to the dedication of many people who care about the future of wildlife.

Project Backyard Observers 2013 – 2016:

by jhwildlife | Feb 18, 2017 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Join us for an annual celebration of our wildlife-friendly community of citizen scientists. The supervisor of the Yellowstone wolf, bird and elk programs Doug Smith will present ‘Yellowstone wolves: the first 20 years’ about wolf population dynamics, wolf-prey relationships, trophic cascades and wolf-human interactions (hunting).

Have some fun and bring a dish to share: Last Name: A-K Main Dish, L-P Side or Salad, Q-Z Dessert

*You are welcome to join us even if you cannot provide a dish

• Nature Mapping Potluck Dinner at 6 pm and Presentation at 7

• At Center for the Arts

• MC: Dawson Smith, Spring Creek Ranch Naturalist Program Director; Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation Board Member

• March 22, 5:30 pm doors open

• Cost: Free (bring some cash for great raffle items!)

Enter a raffle drawing to win from a selection of great items generously offered by in-kind supporters (tickets are 1 for $5, 5 for $10, 10 for $30).

TIMELINE:

5:30 pm – Doors open

• Raffle items and silent auction on display

• Learn about becoming a Nature Mapper and see what our collective observations reveal in maps that are on display

• Drinks available at cash bar

6 pm – Potluck dinner begins

6:50 pm – Raffle ends

7 pm – Presentation in auditorium features Doug Smith

Thanks to the Meg and Bert Raynes Wildlife Fund and the entire Nature Mapping community for making the evening possible.

SILENT AUCTION ITEMS AND RAFFLE PRIZES:

Silent Auction Items:

• Henry Holdsworth Framed Print of Wolves – Last of the Druids donated by Wild by Nature Gallery

• Breakfast with Eagles Float Trip donated by Jackson Hole Vintage Adventures

• Teton Pines Golfing for Four package donated by Teton Pines Country Club

• Lost Creek Ranch Cookout donated by Lost Creek Ranch

Raffle Prizes:

• Bert Raynes Bird Lovers Package (Special edition of Birds of Sage and Scree, Birds of Jackson Hole, and Far Afield DVD)

• National Park Service Annual Pass & Gift Basket donated by Grand Teton Association

• Spring Creek Ranch – One-Night Stay + Breakfast & Dinner for 2 donated by Spring Creek Ranch

• 2 Day Passes to Jackson Hole Mountain Resort donated by Jackson Hole Mountain Resort

• 5-Pack Yoga Class Card donated by Teton Yoga Shala

• Big R gift card donated by Big R Jackson Hole

• Nature Mapping Jackson Hole Hat and T-shirt