by jhwildlife | Jan 27, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation

The Teton County Sheriff’s Office contributed two more variable message signs to a stretch of S HWY 89 as area organizations enacted emergency options to address a challenging winter for wildlife.

We have all seen that this year’s snowpack is making things difficult on wildlife. Mule deer in particular are spending more time in the town and on the roads – wherever they can find easier movement and potential forage. As they join us on the valley floor and move around where we do, the potential for conflict of many kinds increases. An obvious problem arises on our roadways, as high snowbanks both limit driver visibility and make navigation challenging for wildlife. Area organizations and agencies continue to discuss options to address the issue, some having been put in place immediately as short -and long-term strategies to reduce wildlife vehicle collisions are integrated. Here’s an update on the quick-response efforts:

Jackson Hole News & Guide article by Mike Koshmrl (Thursday, January 26)

A small herd of bighorn sheep is frequenting the stretch of N HWY 89 just north of the Dairy Queen near the town limits. Please give them ample space and time to move. Unlike deer and elk, these sheep will obstinately remain on the road.

While a county-wide master plan is in process, an array of short-term mitigation measures have been and will continue to be considered. We are grateful that a good deal of data exists on the relative effectiveness of various measures, which we use to make decisions while also recognizing the constraints of time, resources and feasibility. The planned crossings on South HWY 89 (construction set to begin next spring) will separate animals from the roadway, which data suggests is the most effective way to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions at scale. According to most research, underpasses and overpasses are 80-90% effective at reducing WVCs, while seasonal wildlife alert signage (i.e. variable mobile message signs) is estimated in the 20-25% effective range, making it an effective emergency measure and complimentary piece within a holistic WVC reduction effort. The master plan will likely include a number of mitigation recommendations to include structures, signs and speed limit adjustments to apply the most effective site-specific solutions across the valley.

What can you do now?

- Be alert and drive for the conditions. Most accidents happen at times of low visibility – dawn, dusk, nighttime or in bad weather.

- Watch for electronic warning signs. These signs are put in places where we know animals are or have recently been crossing the road frequently. They’re not just generic warnings – when you see these signs, watch carefully for wildlife.

- When you see wildlife near roadways – slow down immediately. If you see one animal cross the road, it is very likely more are close behind. Animals near the road are not waiting for us to pass by – expect them to do something unexpected, like dash in front of your car.

- In winter, wildlife often use roads to move about – it’s easier than walking through deep snow. But, sometimes they get onto a road and can’t find a quick place to get off. Give them a brake. Be patient and give them time to find a place to get off the road.

- To protect yourself and your passengers, experts advise that you should not swerve off the road to avoid hitting an animal.

- Familiarize yourself with the wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots (located here) and be even more mindful when driving there. Hint: The flashing fixed radar speed limit signs and digital message boards are located in some of these hotspots.

- Get involved with Safe Wildlife Crossings for Jackson Hole to learn about what we can do to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions as a community.

- Contact your elected officials to let them know that reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions is a high priority.

- If you see areas where snowbanks are trapping wildlife on roadways or impeding movement unusually, please don’t hesitate to call us at 307-739-0968. We work with local partners to address these issues if possible.

Additionally, if you are a Nature Mapper, record your observations of wildlife around neighborhoods and roadways. Please use the comments fields to share the activity you observe. The more information we collect about locations and behaviors during winter (all seasons, actually), the better we understand as a community how we are interacting with wildlife, with the goal of living compatibly alongside our wild neighbors.

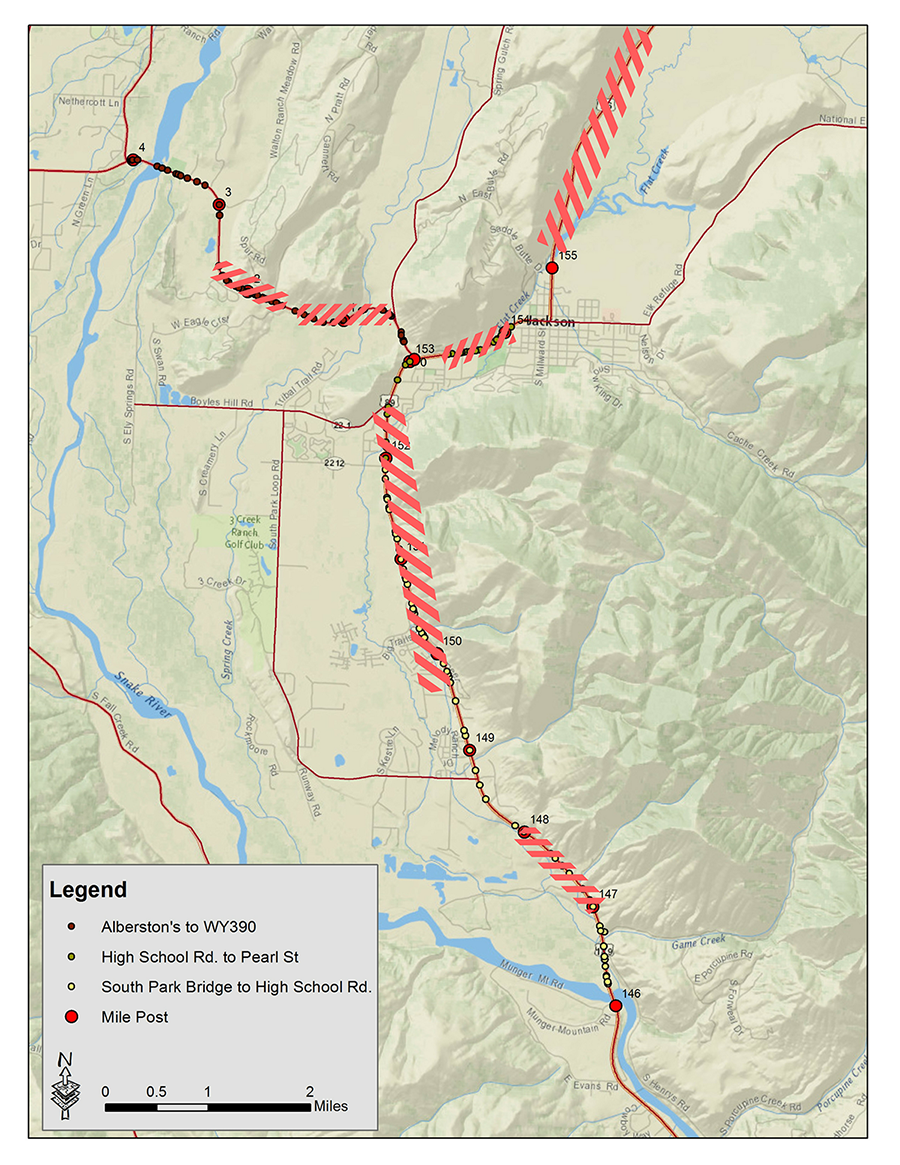

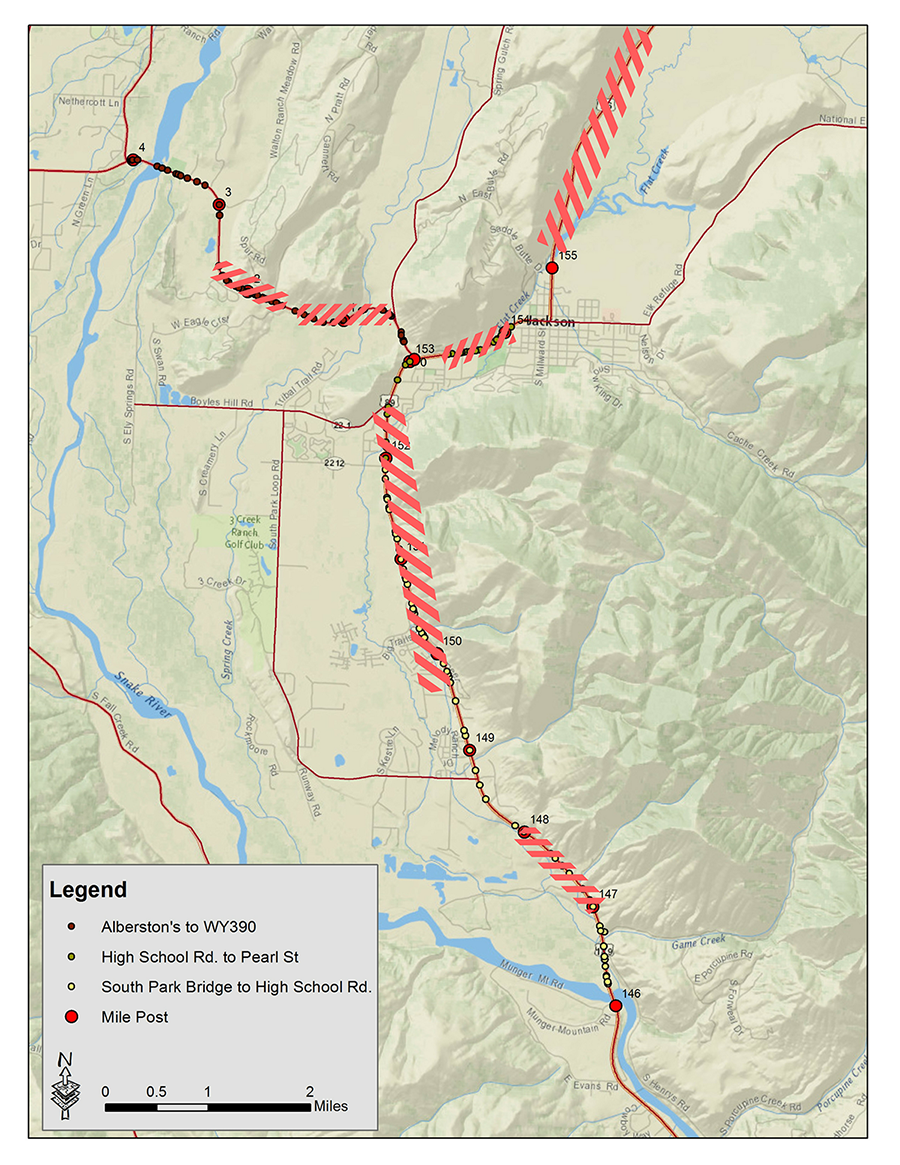

Be especially alert in the areas highlighted on this map!

by jhwildlife | Dec 16, 2016 | Blog, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

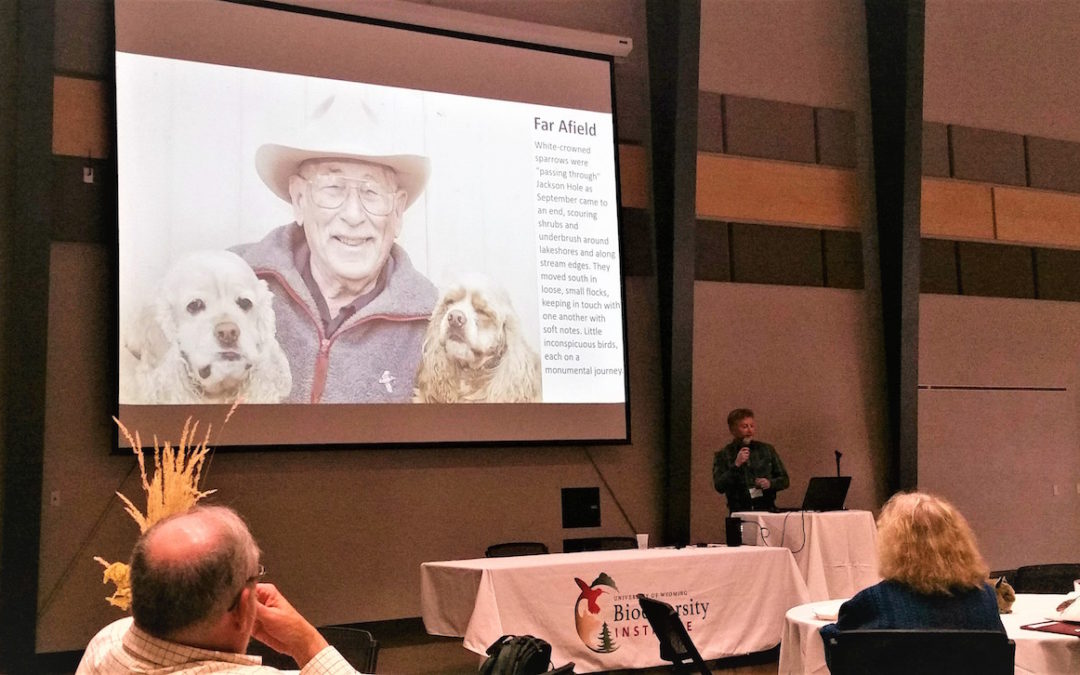

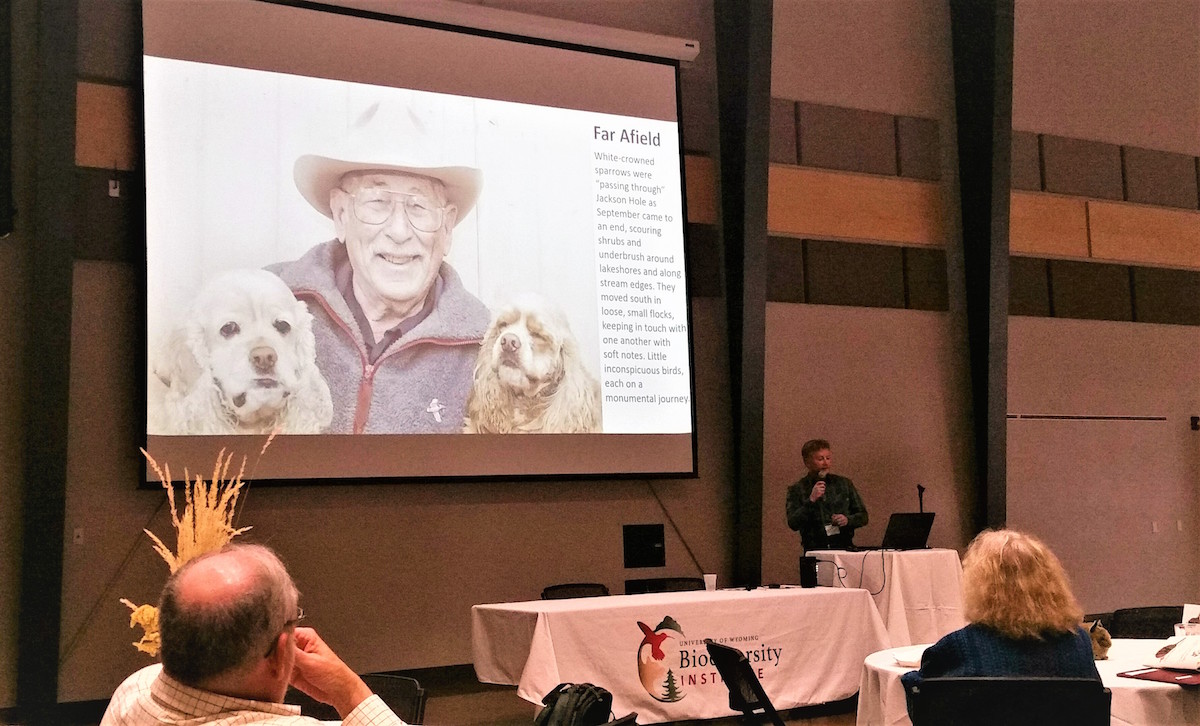

JHWF ED Jon Mobeck presents on the artistry of citizen science and the conservation legacy informing Nature Mapping Jackson Hole.

Earlier this month the University of Wyoming Biodiversity Institute hosted the first ever Wyoming Citizen Science Conference in Lander. Several representatives from the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF) and Nature Mapping Jackson Hole (NMJH) attended the conference with the aim of learning from other citizen science practitioners across the state and of sharing what we have learned from the past eight years of running our program. The conference proved to be very valuable.

The variety of citizen science programs represented was immense and indicative of the breadth and depth available in Wyoming. For example, modeled on NMJH, Laramie sponsors both a winter and summer “Moose Day” with up to 38 transects and over 80 volunteers. Rocky Mountain Amphibian Project conducted a survey of chytrid fungus in frogs and toads throughout the state, including Teton County. A PhD student studied how geo-tagged imagery can enhance surveys by providing follow-up ID, unbiased assessments, and long-term documentation of plants and animals. Museums around the country are recruiting citizen scientists to review historical specimens, including label information on University of Wyoming herbarium sheets. Road Scholar (formerly Elderhostel) volunteers are chronicling archaeological sites in the Wind River Mountains. Associated with the North American Butterfly Association, twenty citizen scientists have tracked approximately 28 species of butterflies in a count circle in Lander for a decade. These are only a few of the amazing projects presented.

The core focus of the conference was on the problems and solutions that citizen science program managers and volunteers face. Several speakers talked about the difficulty of designing data sheets that capture essential information while also being user–friendly. Project directors need to enter and analyze data relatively quickly to keep citizen scientists engaged: volunteers are rewarded by seeing results of their work. Social occasions help build a concerned community. While ensuring quality remains challenging, with sufficient training citizen scientists produce solid scientific data. For instance, the Rocky Mountain Amphibian Project compared the quality of data collected by volunteers vs. bio-techs with very similar results. In short, presenters concluded, “Citizen scientists rock!” And we have a lot to learn from each other.

Our role in the conference:

On the whole, 65 conference participants came from across Wyoming, and even Idaho and Vermont too – all from a mix of individual citizen scientists, nonprofit organizations, primary and higher educational institutions and federal agencies.

JHWF was a silver-level sponsor for the Wyoming Citizen Science Conference, and our Associate Director Kate Gersh served on the program planning committee, which helped select presenters and set the agenda. Over the course of nearly two full days, here are a few programs that were presented by JHWF board, staff, and partners:

- “Lessons Learned: Eight Years of a Citizen Science Program in Jackson Hole” – Aly Courtemanch

- “Values Driving Conservation: Citizen Science as Interactive Art” – Jon Mobeck

- “Fundraising for Citizen Science: Experiences and Advice” – Kate Gersh, Anya Tyson, Wendy Estes-Zumpf, Frances Clark (in absence)

- Poster Presentation: Nature Mapping Jackson Hole: Mapping Community Solutions ̶ Kate Gersh

- Poster Presentation: Monitoring Wildlife Crossings on South Highway 89 ̶ Paul Hood

- “Bringing Citizen Science into the Backcountry: Emerging Best Practices to Engage Outdoor Education Organizations” – Anya Tyson

- Screening of Far Afield: A Conservation Love Story

Importantly, one of NMJH’s lead volunteers Tim Griffith attended the conference and contributed much to the conversation. Based on the latter and the abovementioned, we believe we successfully expanded awareness of Nature Mapping Jackson Hole statewide and regionally, thereby opening opportunities for greater community connections. This was a proud experience for us and we feel honored to have represented on behalf of everyone who has been involved with NMJH.

Next steps for Citizen Science

What comes next? Well, based on survey responses, conference participants have expressed a desire for open communication and collaboration between citizen science groups, as well as, one central location to list project information. The Biodiversity Institute is excited to share that they have begun the process of planning a website to act as a citizen science clearing house. It will provide a forum for discussion around citizen science projects in our region and to glean tips and ideas for best practice. It will also help to incorporate our projects into the classroom. In addition, the idea of a dedicated newsletter for citizen science groups in Wyoming is under discussion.

The hope is that this conference will take place again next year, giving us the opportunity to follow-up on tactics and ideas that were shared. We have much to learn still about volunteer recruitment and retention, fundraising, risk management, data collection and submission, data sharing and dissemination, evaluation and the list goes on. JHWF will be sure to keep you updated on new developments as they come about. Stay tuned as we continue to explore the potential of all that Nature Mapping Jackson Hole has to offer!

by jhwildlife | Dec 14, 2016 | Blog, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

One of the perks of working for the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation is that occasionally you get invited by local scientists to do really, really cool stuff! Case in point, this past weekend staff traveled into the Gros Ventre Range with a crew of researchers to briefly capture, study and release bighorn sheep. Witnessing a small helicopter carrying blindfolded, restrained sheep at one or two at a time is very cool! This might sound alarming to some, that sheep would be transported from location to location via helicopter, but be assured that the animals are caught in the shortest possible time, with the least amount of stress. Furthermore, the purpose for this “trip of a lifetime” is to conduct science that will ensure the long-term survival of this iconic species of the American West.

The helicopter brings in two bighorn sheep for a gentle landing.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) is continuing its multi-year research project on bighorn sheep in the Jackson Region. On December 10 and 11, 2016, 10 female bighorn sheep (previously fitted with radio collars) were captured for disease testing in an effort to learn more about their survival and migration patterns. Samples were collected to test for respiratory pathogens that can cause pneumonia. In addition, researchers from Dr. Kevin Monteith’s lab at Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Wyoming performed an ultrasound on each animal to measure body fat. This is a three-year study evaluating how body condition is related to pneumonia outbreaks.

The Jackson herd, which numbered 500 animals in the 1990s, has experienced two significant die-offs in recent years. In 2001, it was estimated that as many as 50% was lost due to a pneumonia outbreak and another estimated 30% lost again in 2011. Today it is estimated that the Jackson herd has climbed back to around 425 animals currently.

Kate Gersh and Greater Yellowstone Coalition wildlife program coordinator Chris Colligan assist the research team.

By monitoring individual female bighorn sheep (ewes) through time, researchers are assessing nutritional condition, pneumonia infection, and linking those data to reproductive performance, survival, and nutritional condition in subsequent seasons. At a minimum, they hope to begin to shed light on the complex interactions in the population dynamics of bighorn sheep and help identify possible management alternatives to reduce probability of pneumonia die-offs. For this specific research project, approximately 20 ewes have been collared. During the first three years of this project, biologists are expecting to recapture these same individual sheep each spring and fall to perform the same round of tests and evaluations. The team will go out again in March 2017, and attempt to catch more of their collared ewes to ascertain pregnancy and other health conditions.

JHWF staff is grateful to have been included in this project over the weekend and we thank the WGFD and Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit for allowing us to see first-hand the efforts involved in conducting field research on bighorn sheep. We also thank all those involved for continuing to support wild sheep conservation efforts — you are doing excellent work!

View an image gallery of the work here.

References:

Bighorn Sheep Surveillance. (2016, March). Wyoming Game and Fish Department: Jackson Region Monthly Newsletter, 1. Retrieved December 13, 2016, from https://wgfd.wyo.gov/WGFD/media/content/PDF/Regional Offices/Jackson/2016_Mar_Jackson.pdf

Interview with Aly Courtemanch, Wildlife Biologist with Wyoming Game and Fish Department [Telephone interview]. (2016, December 13).

Koshmrl, M. (2015, March 25). Bighorns get their checkup. Jackson Hole News & Guide.

Nutritional dynamics and interactions with disease in bighorn sheep. (n.d.). Retrieved December 13, 2016, from http://wyocoopunit.org/projects/nutritional-dynamics-and-interactions-with-disease-in-bighorn-sheep.

by jhwildlife | Oct 11, 2016 | Blog, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

By Frances Clark, Nature Mapper and Botanist

Hiking under Engelmann spruce trees has been hazardous this fall. Light brown cones, 4-6 inches long and sticky with pitch, pour down amidst harsh chattering from above. I have counted one cone falling every 3-5 seconds, another time I couldn’t keep track of the barrage. Cones landed on my head, bounced and then lay strewn about my feet. Cone storms. What s going on?

Red squirrels are taking advantage of a “mast year.” Last spring, you may remember, prodigious amounts of pollen wafted on the wind. Some of that pollen landed on tiny female cones, which have matured, securing two winged seeds under each scale. Spruce trees are now laden with dangling cones from the top down. This abundance occurs every 2-3 years in spruce. The intervening times are lean.

Red squirrels are taking advantage of a “mast year.” Last spring, you may remember, prodigious amounts of pollen wafted on the wind. Some of that pollen landed on tiny female cones, which have matured, securing two winged seeds under each scale. Spruce trees are now laden with dangling cones from the top down. This abundance occurs every 2-3 years in spruce. The intervening times are lean.

Well adapted to feast and famine, red squirrels form large middens—stores of thousands of cones. They efficiently sample and then harvest trees with the most seed energy per cone and with the greatest cone abundance. Middens lie at the center of the most productive group of trees.

A midden can best be described as several inches of cone scales and cores heaped over mineral soil, forming mounds up to several feet high and wide. The loose surface often has shallow holes in it. In the mineral soil below, there may be a network of tunnels. Squirrels pack several cones, pointed end down, into holes which will be covered eventually by more scales and cores. In this cool and moist environment—a humidor—cones will remain unopened for at least 1-2 seasons until the squirrels retrieve them. When they do, squirrels eat cones like corn-on-the-cob, scattering scales everywhere while consuming the nutritious seeds. It has been calculated that squirrels consume 50-156 cones a day and stash 10s of 1000s in a midden in a good year. No wonder red squirrels are so territorial – chattering loudly at any perceived threat and dashing out to their territorial boundary: they are defending their stash for winter survival.

While cones are preferred, in lean times and in summer, red squirrels will eat other items. Fungi are particularly relished, with parts hung up in trees to dry. They eat buds, fruits, sap, even cambium and phloem, as well as eggs and insects. Small plant parts placed in middens may help train young squirrels for future hoarding. In different years, squirrels may harvest cones of Douglas firs – which have mast years every 4-5 years, or as back up, serotinous cones of lodgepole pine. Lodgepole pine cones are often gathered on top of middens. They do not open even when dry, are too tough for other predators to eat, and seeds remain viable for years. The squirrels don’t need to spend extra energy to bury them.

The other day, walking around Moose Ponds, I heard several red squirrels churring within a stand of battered old spruce and fir trees. Their density indicated good habitat. Tangles of downed limbs and saplings surrounded straight, scaly boles clad in densely needled branches, which intertwined to form a closed, irregular canopy. Engelmann Spruce reach peak production at 150-200 years and provide diverse cover, escape routes, and nesting sites. Old growth trees are excellent for red squirrels.

As red squirrels are active all winter, nesting sites are vital for thermal regulation. Tree squirrels prefer natural cavities, but these are often in short supply so instead squirrels will build a nest of leaves and grass 12 to 60 feet off the ground. Other options include “witches brooms,” an aberrant growth pattern where twigs are unusually dense. They will also burrow into tunnels under their middens for warmth and safety.

Nest sites are located within 100 feet of larders so squirrels can readily defend and retrieve their stores. Circular territories may be 1-2 acres centered around a midden. I nature mapped six squirrels – six territories – on my route past Moose Ponds. While dutiful, I wish now I had taken more time in this rough old patch of forest to see where the middens and nests might be.

Predators come from air or ground. Squirrels may have different calls depending on whether or not a threat is aerial or terrestrial. One study indicates that red squirrels produce a high frequency, short “seet” sound similar to alarm calls of birds. This sound is hard for raptors, such as Goshawk, Great Horned Owl, or Red-tail Hawk , to locate or even hear. A louder bark call is used for overland threats, such as a Pacific (pine) marten (12-20% of marten diet is red squirrels), weasels, or fox. Once alerted, squirrels scramble and hide in dense vegetation.

Between predation and starvation, only 25% of squirrels survive into their second year. Females are in estrus for one day only in early spring. Many males, one dominant in the lead, will give chase and several may succeed in copulation on that one day. In just over a month, the female gives birth to an average of four young which will be independent in another 70 days, by early fall. While mothers may share a territory with daughters, they kick out sons who must then find and defend their own territories by winter. Often the most successful males have ventured the farthest to find a relatively large territory containing an abandoned midden. Midden sites are often used by many generations. In autumn, youngsters and seasoned squirrels are particularly territorial, defending boundaries while gathering cones, which is why they are so vociferous.

Red Squirrels are the most frequently Nature Mapped small mammal with 305 observations over the last seven years. Even so, many of us pass them by – unrecorded – on our hikes. In your next excursions through a conifer forest, listen for chatter. Can you hear differences in their calls? Can you discover a midden nearby? Does a squirrel bound toward you to defend its territory or scurry up a tree or down into a tunnel to escape? Can you find its nest? All these behaviors are fascinating to watch while you may, or may not, log a new Nature Mapping observation.

References:

Animal Diversity Web ADW: Museum of Zoology University of Michigan. Tamiasciurus hudsonicus Red Squirrel. Accessed 10.8.16: http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Tamiasciurus_hudsonicus/

Finley RB. Cone caches and middens of Tamiasciurus in the Rocky Mountain region. Misc. Publ. University of Kansas Museum Natural History. 1969;51: 233–273. https://archive.org/stream/cbarchive_36740_conecachesandmiddensoftamiasci1969/conecachesandmiddensoftamiasci1969 – page/n17/mode/2up

Greene E. Meagher T. 1998. “Red squirrels, Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, produce predator-class specific alarm calls.” Animal Behavior. 1998 Mar; 55(3): 511-8. Accessed through: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9514668

Steele, M.A. 1998. “Tamiasciurus hudsonicus” Mammalian Species 586, pp. 1-9. : published by the American Society of Mammalogists. http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-586-01-0001.pdf

Streubel, D. P. 1968. “Food storage and related behavior in red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) in Interior Alaska.” Masters Thesis. University of Alaska. Source: http://www.arlis.org/docs/vol2/hydropower/APA_DOC_no._3351.pdf

U.S. Forest Service data base: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/animals/mammal/tahu/all.html

by jhwildlife | Aug 8, 2016 | Blog, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

For thirteen years, volunteers have been maintaining a bluebird trail along the boundary of the National Elk Refuge. It is the largest Mountain Bluebird trail in the United States, and it provides essential nesting habitat for these iconic birds, as well as long-term scientific data. This citizen science project is core to the mission of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation: Combining science and the celebration of wildlife.

About Mountain Bluebirds

A male Mountain Bluebird. Photo: Chuck Schneebeck

The brilliant-blue males arrive in Jackson Hole starting in March and begin to select and defend boxes. The pale blue-gray females arrive shortly thereafter and choose a mate based solely on the quality of the nest cavity. They build the nest to fit several eggs—similar in color to Robins’ eggs, but smaller. The males feed the incubating female, often hovering and diving to catch insects such as beetles and grasshoppers.

Phyllis Greene, long-time monitor and past project coordinator, has observed: “They lay one egg a day, but the eggs hatch out all at once. It’s fun to watch. I have seen the chicks peck out through the shell. When they hatch, they are the size of your pinky and nude. First thing, they have their mouths open for food. They are adorable.” The chicks develop pin feathers and then “become more of a bird.” The monitors observe the nestlings from afar after the first 12-14 days so that the birds won’t fledge prematurely. Then after about 3 weeks total, ”They fly off. ‘Ok, good-bye.’ It’s sad. They are so gorgeous.” Adult males depart Jackson in early August. The females and young leave a little later. These birds, considerably smaller than a robin, migrate as far south as Mexico and Central America.

Nesting success is tenuous. While Tree Swallows arrive two weeks later than Mountain Bluebirds – after many bluebirds have claimed boxes – they often out-compete the bluebirds when they would otherwise attempt a second brood. Tree Swallows are a beautiful, native bird, so their presence is enjoyed as well, despite the challenge to bluebirds. Future nestbox plans aim to accommodate the greatest number of both species. Also, according to project coordinator Tim Griffith, weasels and raccoons have been known to raid the nests, which lowers the success rate. Overall, the North American Breeding Bird Survey indicates Mountain Bluebird populations declined by about 26% between 1966 and 2014. We will continue to analyze our data to see how the birds have been faring here in Jackson Hole.

The Origin of the Mountain Bluebird Nestbox Trail Project

Female Mountain Bluebird. Photo: Chuck Schneebeck

Chuck Schneebeck started the project in 2003. He read a study about the loss of aspens due to intensive ungulate grazing on the National Elk Refuge (NER). Bluebirds are cavity nesters, naturally using holes in old aspen trees carved out by woodpeckers or formed by a rotted tree limb. On the Refuge, the loss of standing aspens due to elk browsing meant the loss of nesting habitat. In an informal survey, “We found only one nest from Flat Creek to the Gros Ventre River, in an electrical box by the visitor center.” Chuck realized that to mitigate the impact of grazing, “We could build cavities: nest boxes.” Having worked on a bluebird trail for the National Audubon Society in Dubois, WY, he knew how to start.

From the beginning, Chuck engaged the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and community. The Foundation provided funds for the materials and Chuck donated his labor. With the cooperation of NER, he and others set up 105 boxes 100 yards apart placed five or more feet high along the western boundary fence. Citizen science volunteers were assigned about 15 boxes each, which requires a mile walk and about an hour a week to monitor. They start surveying in April and continue into August. Monitors also help clean out and repair the boxes in the off-season.

The Monitoring Process

Kate Gersh, JHWF Associate Director and project monitor

Phyllis Greene’s approach is, “We talk to the box and tap first, saying ‘Hi, coming to see you. How you are doing?’ Then we open the lid and look in. Mom just looks up and blinks her yes and says ‘how do you do?’ We close the lid then record what we saw. They don’t mind the monitoring and we never touch them.“

Phyllis goes on to say that the monitors become “very maternal or paternal. We want to give the birds a chance because they are almost extinct out here.”

While monitors are surveying along the road, people often stop and ask what they are doing. “We explain the project and they respond, ‘That’s great!’ People get excited and appreciate that someone is doing something for these little birds,” recalls Phyllis.

How do volunteers feel about the project?

For Chuck Schneebeck – project founder – while the project does not supply all the complexity that the bluebirds need, “We are doing what we can. The fundamental part is that we have cavities and bluebirds have been using them for a long period of time. So there are lots of birds now.”

Phyllis Greene, who took over the project from Chuck: “The important thing is for the birds to have an opportunity to have a nest, to get out of the weather and survive. We want to make sure they have a chance. Originally they were almost extinct in lots of places throughout the US, not only here. Anytime we can help wildlife sustain itself and still be independent is a great idea.”

Jon Mobeck, Executive Director of JHWF says the project fits the mission of the organization. “This is a visible way to demonstrate how to mitigate our impacts of development on wildlife. It is a perfect example of the community coming together and helping out this beautiful species. It combines science and the celebration of wildlife.” And more personally, Jon had no experience with birds prior to taking on 12 boxes with the JHWF staff. He is becoming a bird watcher. “Now I have a whole new way of observing the environment. It has been eye opening and ear opening. A tremendous gift.”

Tim Griffith, our new project coordinator, has been engaged with Eastern Bluebird trails for years in Indiana before moving here a year ago: “This is the largest registered Mountain Bluebird Trail in the continental U.S. Mountain Bluebirds are crashing throughout the region. With 13 years of data, we can know more about the population and be responsive to changes in trends upward instead of downward. The more we know about this iconic western species the more we can save and increase their populations here and elsewhere.”

Natalie Fath, Volunteer Coordinator and Visitor Services Manager for the National Elk Refuge: “The ongoing collaboration with the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation on the Mountain Bluebird Nestbox Trail Project is essential to ensuring that monitoring, box maintenance, and reporting occurs. The NER is not only supportive of the collaboration, but also depends entirely on volunteer citizen scientists to give this project life due to Refuge full-time staffing limitations. Without volunteers, this project would not exist.”

Future Plans

A male bluebird watches as a monitor approaches. Nestlings are getting ready to fledge.

Next year, Tim plans to start banding birds to see how many return, and to which boxes. Eagle Scouts are ready to repair and build more boxes to place at other areas in the Refuge. Also, we will digitize the years of data for submission into our Nature Mapping database and Cornell’s national NestWatch system.

Jon Mobeck sums it up, “The Nature Mapping Bluebird Nestbox Project is a great way to introduce citizen science to the community. It is a visible and fun project. We welcome new volunteers!”

We thank the ongoing core project volunteers who are still in the valley:

Chuck Schneebeck, Ed Henze, Bert Raynes, Paul Anthony, Phyllis and Joe Greene, Loretta Scott, Larry Kummer, Julianne O’Donoghue, Gretchen Plender, Shelly Sundgren and Dave Lucas; Jon Mobeck, Kate Gersh, Christine Mychajliw, Tim Griffith.

Additional thanks to Jackson Lumber, which often donates cedar wood for the boxes.

Contact Tim Griffith to help out: Timgrif396@gmail.com.

References:

by jhwildlife | Jun 23, 2016 | Blog, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

In June, JHWF was visited by a group of conservation professionals from Argentina, Russia, Iran, Sierra Leone, Malaysia, South Africa, Morocco, Sri Lanka, Oman and Zimbabwe. This group was supported by the International Visitor Leadership Program of the U.S. Department of State and hosted by our friends at the Wyoming Council for International Visitors.

Traveling with the objective of assessing U.S. efforts to protect biodiversity, JHWF was pleased to spend an hour with our new colleagues talking about wildlife-friendly communities. There was great interest in learning more about the citizen science effort throughout the valley and how the Nature Mapping program was designed. Citizen science is not (yet) a strong practice in many other countries, but there is growing interest to engage the public in conservation science. We said that one of the keys to launching a successful citizen science effort is to have a “champion,” such as the admired and beloved Bert Raynes, to inspire an initial following.

A visiting biologist from Morocco inquired about the bluebird nest boxes he observed along the Elk Refuge fence. “I noticed more tree swallows than bluebirds as we drove into town,” he said. His observation concurred with our findings in recent weeks, as many of the Mountain Bluebirds and their fledglings had left the boxes, though a few remain. While we delighted in the fact that nearly every representative expressed interest in introducing a variation of Nature Mapping in their country, we also couldn’t help but recognize the common joy we all derive from our interactions with wildlife – a universal bond.

It was an interesting discussion comparing and contrasting our conservation challenges and subsequent efforts around the world. While our working contexts might differ in terms of political, social and economic influences, a consistent thought existed amongst our diverse group – the belief that by removing or reducing barriers we humans have created (obsolete barbed wire fencing, for example), we can moderate our impact on wildlife and live more compatibly within a healthy environment that sustains all life.