By the JHWF Staff As wildlife conservation professionals, we remind ourselves to celebrate the successes. Sometimes we get so wrapped into understanding and mitigating the challenges facing wildlife that we feel frustrated. In these moments, it is sometimes in our...

The Mountain Bluebird: A Welcome Sign of Spring

There are few sights in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem more uplifting than the flash of brilliant blue wings cutting across a wide-open field. That’s the male Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides)—a vibrant burst of color against the earthy hues of Wyoming’s landscapes. While the females are more understated in appearance, with gray bodies and soft turquoise on their wings and tails, both sexes are a welcome sign of spring and a vital part of our ecosystem.

Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation protects and supports the mountain bluebird through:

Nesting support – Providing essential nesting sites through the Mountain Bluebird Project.

Collection of scientific data – Monitoring bluebird populations to gauge ecosystem health and stability.

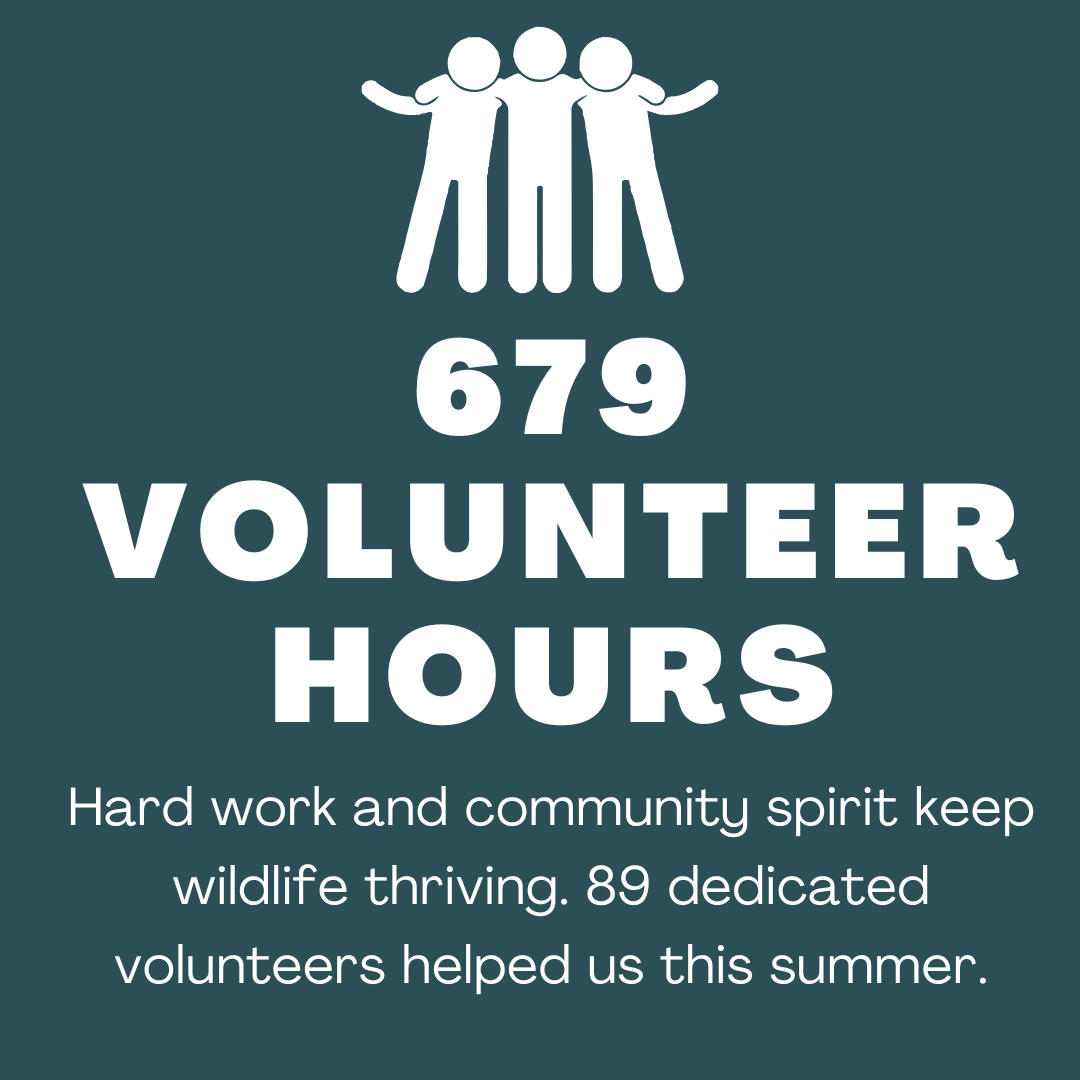

Community involvement – Engaging volunteers in meaningful conservation efforts through Nature Mapping and the Mountain Bluebird Project.

The Mountain Bluebird Project

Mountain Bluebirds are cavity nesters, but unlike woodpeckers, they can’t carve out their own nesting spots. Instead, they rely on natural cavities or those created by other species—including us. That’s where our Mountain Bluebird Project comes in.

By installing and monitoring nest boxes in key spots in Jackson, JHWF provides critical nesting habitat for bluebirds in places where natural cavities may be scarce. These human-altered landscapes might not seem ideal, but bluebirds have adapted remarkably well to them—especially when given a safe place to raise their young.

A Species Worth Watching

Mountain Bluebirds are more than just beautiful—they’re indicator species, meaning their presence reflects the health of the ecosystem around them. That makes monitoring their population trends a key part of broader conservation work.

In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, data is limited but encouraging. Long-term surveys show that bluebird populations in the Northern Rockies are generally stable, with slight but positive trends. In Wyoming, however, there’s been a slight decline, although it’s not statistically significant. These trends highlight the importance of continued support for habitat access, especially as natural nesting cavities become more scarce due to habitat loss and competition from other cavity nesters.

Did you know?

Mountain Bluebird feathers aren’t actually blue. The color we see comes from structural coloration—an interaction between light and the microscopic structure of their feathers. Like a prism scattering light, the feathers absorb all wavelengths except blue, which is refracted back to our eyes. The result? That signature, radiant blue hue.

The Mountain Bluebird and You

Thanks to projects like the Mountain Bluebird Program and the dedicated volunteers who support it, these sky-colored conservation ambassadors continue to thrive in Jackson Hole. Their presence reminds us of the delicate balance of nature—and the impact we can have when we lend a hand.

If you spot a Mountain Bluebird perched on a fencepost or fluttering through a field, take a moment to enjoy the view—and then consider recording your sighting through Nature Mapping Jackson Hole. Community science efforts like Nature Mapping provide valuable data that helps biologists track bird populations and better understand local ecosystem health. Every observation adds to the bigger picture of conservation in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Observing with Care

Each spring, JHWF offers a limited volunteer opportunity to join a guided nestbox monitoring expedition. These experiences are designed to be educational, giving participants a firsthand look at the work involved in protecting Mountain Bluebirds and the broader importance of cavity-nesting birds.

To protect the birds, there is no hands-on interaction with the nestboxes or bluebirds. All observations are done from a respectful distance under the guidance of trained staff. Mountain Bluebirds are especially sensitive during nesting season, and disturbance can lead to nest abandonment, stress, or disrupted feeding. That’s why participation is limited and carefully managed—to balance education with wildlife safety.