by jhwildlife | Mar 17, 2025 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake

As spring arrives, wildlife activity increases, posing challenges for safe coexistence on roadways.

Understanding Seasonal Changes

With the onset of spring, Jackson Hole becomes a hub of wildlife activity. Animals such as elk, deer, and moose embark on their traditional migration journeys, often intersecting with busy roadways. This natural phenomenon, while extraordinary to witness, brings about significant risks for both the animals and drivers. Increased vigilance and strategic measures are essential to ensure safety for all.

A Tragic Incident on N HWY 89

One incident illustrated the importance of strategically placed wildlife crossings to move wildlife safely across high traffic roadways. Recently, JHWF Board Member Kathryn Turner was traveling southbound on Highway 89 when she witnessed a near collision between a bull elk and a START bus. The elk, attempting to cross between the U.S. Fish Hatchery and the National Museum of Wildlife Art, barely avoided the bus’s path. The next morning, she discovered that bull elk, now deceased, in the same area.

“I saw what appeared to be the same bull elk lying dead near the road,” said Kathryn Turner. “Bloody tracks led to the edge of the Elk Refuge fence, but with a broken leg, the jump would have been impossible. If an overpass had been in place, this elk might have survived, and a costly, dangerous collision could have been avoided.”

The Ripple Effect of Collisions

Wildlife-vehicle collisions leave a trail of destruction, from vehicle debris to the tragic loss of human and animal life. The aftermath of such incidents can attract scavengers, increasing their risk of being hit. This cycle of danger highlights the critical need for effective wildlife crossings. By investing in overpasses and underpasses, we can safeguard migration routes, reduce vehicle damage, and enhance road safety.

Steps to Reduce Wildlife-Vehicle Collisions

Reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions requires a multi-faceted approach that involves both infrastructure improvements and driver awareness. By following these steps, we can significantly decrease the number of incidents and enhance safety for all.

Implement Wildlife Crossings

Constructing wildlife overpasses and underpasses is a proven method to facilitate safe animal crossings. These structures allow animals to follow their natural migration paths without encountering vehicles, reducing the risk of collisions.

Advocate for Traffic-Calming Measures

Rumble strips, narrow lanes, chicanes and other measures naturally slow drivers’ speeds and increase their attention to the road. Work with road designers to consider such measures where they are safe to install.

Promote Safe Driving Practices

Encouraging drivers to remain vigilant for animals on the road, especially during dawn and dusk, can prevent accidents. Drive the posted speed limit and decrease your speed when conditions reduce visibility.

Advocating for Wildlife Crossings

Join the Movement for Safer Wildlife Crossings

Help us make a difference in Jackson Hole by supporting wildlife crossing initiatives. These critical structures not only protect our cherished wildlife but also ensure safer roads for everyone. Your involvement can lead to fewer tragic incidents and preserve wildlife migration paths that are vital for our ecosystem. Together, we can create a safer environment for both animals and humans.

by jhwildlife | Dec 23, 2024 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

do not look both ways before crossing the road

Thousands of elk migrate from the higher elevations of Grand Teton National Park and surrounding areas to lower valleys, seeking food and shelter each winter. This seasonal journey is essential for the survival of the elk herd, but it also brings them into direct conflict with human infrastructure—most notably, busy roads like North Highway 89.

The National Elk Refuge, established in 1912, provides critical winter habitat for the Jackson Elk Herd, which can number as many as 11,000 animals. However, as elk move toward the refuge, they frequently cross North Highway 89, a major route connecting Jackson to the park.

These crossings often occur at dawn and dusk, when visibility is limited, increasing the risk of vehicle collisions. This time of year, elk are on the road in larger numbers, and Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, with partners Wyoming Game and Fish and Teton County, has reported a rise in roadkill incidents along this corridor.

The Challenge on North Highway 89

North Highway 89 sees heavy traffic year-round, and during elk migration, it becomes a hazardous bottleneck for wildlife. Data collected by JHWF, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, and Wyoming Department of Transportation shows that wildlife-vehicle collisions are a significant cause of mortality for elk, moose, and deer in the region. For drivers, an unexpected collision with a 600-pound elk can cause severe damage, injuries, or fatalities. Human safety and wildlife preservation are intertwined, making solutions to this challenge a community priority.

Proposed Wildlife Crossings

To address the growing problem, Teton County, Wyoming has proposed wildlife crossings and funnel fence at high-risk areas in Teton County, including:

North Highway 89: 3 Crossings (1 Overpass, 2 Underpasses)

- Wildlife Overpass: This structure allows animals to cross above the road on a vegetated bridge, mimicking their natural habitat. Overpasses are particularly effective for larger mammals like elk and pronghorn that prefer open spaces.

- Wildlife Underpasses (2): These tunnels provide safe passage beneath the road, offering an effective solution for animals that prefer cover.

- Funnel Fence: (4 miles) Guided by funnel fencing, the underpasses and overpasses encourage wildlife to avoid the roadway entirely, reducing collision risks.

Teton Pass: 1 Overpass, 3 Underpasses, and a Fish Passage

- Wildlife Overpass: Similar to the North Highway 89 overpass, this structure will reconnect migration routes over the highway, reducing risks for both wildlife and drivers.

- Wildlife Underpasses (3): These underpasses will provide multiple safe routes beneath the Teton Pass Highway for animals such as deer, moose, and smaller mammals.

- Fish Passage: A specialized structure allowing aquatic species to move freely along their natural waterways without obstruction from road infrastructure. This supports fish populations and improves the overall health of the ecosystem.

- Funnel Fence: (4 miles) Guided by funnel fencing, the underpasses and overpasses encourage wildlife to avoid the roadway entirely, reducing collision risks.

Camp Creek: 3 Underpasses and 1 Overpass

- Wildlife Overpass: As with the other overpasses, this vegetated bridge provides a natural, open pathway for wildlife like elk, facilitating their migration while keeping them off the road.

- Wildlife Underpasses (3): These crossings will guide animals safely below the road, preventing wildlife-vehicle collisions and maintaining connectivity across the landscape.

- Funnel Fence: (5.5 miles) Guided by funnel fencing, the underpasses and overpasses encourage wildlife to avoid the roadway entirely, reducing collision risks.

Wildlife crossings, including overpasses and underpasses with funnel fences, are proven to reduce collisions and support healthy migration. A study of similar projects on US Highway 191 near Pinedale, Wyoming, found a 90% reduction in wildlife-vehicle collisions after implementing overpasses and underpasses. This project, monitored by the Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) and other agencies, highlights the effectiveness of combining crossings with fencing to guide wildlife safely above or below roadways. The Trappers Point crossing has become a national model for mitigating migration conflicts.

Scientists emphasize the importance of open migration corridors for ungulates. Fragmented or blocked movement routes can force wildlife into smaller, less suitable habitats, leading to stress, reduced herd sizes, malnutrition, and disrupted ecosystems. By building crossings, we reconnect critical wildlife movement routes and reduce risks for drivers.

A High-Profile Fatality

The recent wildlife-vehicle collision death of Grizzly Bear 399, one of the most well-known bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, highlights the devastating chain reaction caused by wildlife-vehicle collisions. Grizzly 399 and her cub were likely devouring an elk carcass in the Snake River Canyon that was very near to the section of the highway where she was killed. Roadkill draws predators like bears, wolves, and eagles to highways, dramatically increasing their risk of being struck by vehicles. Wildlife crossings can reduce these incidents by preventing collisions that leave carcasses on the roadside in the first place, breaking the cycle that endangers predators and scavengers.

While 399’s passing is a high-profile example of a wildlife-vehicle collision, the need for wildlife crossings extends far beyond any one species or one animal. Her death symbolizes the countless animals—ungulates, predators, birds, and smaller mammals—that lose their lives on roads each year.

Though 399 was internationally beloved and her story has drawn significant attention, she represents all wildlife navigating the dangers of high-traffic areas. We hope her legacy will inspire greater awareness and support for implementing wildlife-friendly crossing structures throughout Wyoming. These solutions have proven effective in reducing fatalities and reconnecting critical habitats, providing a safer future for all species that call this region home.

Give Wildlife a Brake and Nature Mapping: A Community Effort

The Give Wildlife a Brake program, led by JHWF, works to raise awareness and promote safer driving practices:

- Drive mindfully and observe the speed limit in key wildlife zones like North Highway 89, Teton Pass, and Camp Creek.

- Stay alert at dawn and dusk, when animals are most active.

- Observe wildlife warning signs that identify known crossing areas.

- Report collisions and roadkill to help scientists and officials prioritize safety improvements.

In addition, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole offers an easy way for community members to contribute to wildlife conservation. By becoming a certified Nature Mapper, participants can log wildlife and roadkill sightings using an app. The data collected is shared with Wyoming Game and Fish Department to better understand wildlife movements and identify problem areas. This citizen science initiative empowers residents to actively contribute to protecting the animals that define Jackson Hole.

Give Wildlife a Brake and Nature Mapping also work with local volunteers to monitor wildlife crossings, gather data, and educate residents and visitors about the importance of migration corridors.

Elk are an iconic part of the Jackson Hole ecosystem. They support a balanced food chain and play a key role in the region’s cultural and ecological identity. Their winter migration has occurred for centuries, long before roads and cars appeared in the valley. Protecting this natural behavior while improving public safety requires collaboration, science, and community effort.

While this blog focuses on elk migration, the need for wildlife crossings applies to all species in the Jackson region, including mule deer. There is no doubt that wildlife-vehicle collisions pose a significant threat, ranking as the third leading cause of bird fatalities each year. Drivers should remain vigilant, as animals crossing the road are often accompanied by others, including offspring or members of a herd, making caution essential for reducing collisions.

Review the Wildlife Vehicle Collision Report to learn more about the scope of this issue and the need for wildlife crossings as a proven solution. Support efforts to fund and implement wildlife crossings and participate in programs like Give Wildlife a Brake and Nature Mapping Jackson Hole to make Jackson Hole safer for wildlife and people.

by jhwildlife | Nov 17, 2024 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake

The Life and Legacy of Grizzly 399

On the evening of October 22, 2024, a routine commute through the Snake River Canyon turned tragic. Near milepost 126, a grizzly bear and her cub were feeding on an elk carcass when they attempted to cross the road. A commuter traveling at the legal speed limit of 55 mph swerved, narrowly missing the cub but tragically struck and killed the mother. This was no ordinary grizzly—it was 399, the most famous grizzly bear in the world.

The Road Ahead

A post-mortem analysis concluded that the collision was unavoidable. At highway speeds, drivers often have little chance of safely avoiding wildlife that appears suddenly. This heartbreaking incident underscores the critical importance of programs like Give Wildlife a Brake, which aims to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions through driver awareness and infrastructure improvements.

A Community Commitment to Wildlife Safety

The Give Wildlife a Brake program is a cornerstone initiative of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF). Its mission is to protect wildlife and motorists by identifying high-risk areas and implementing strategies to reduce collisions and increase access to critical habitats. Through public education, advocacy for reduced speed limits, and the installation of wildlife crossings, the program seeks to make our roads safer for all.

In the wake of 399’s death, the urgency of this mission has never been clearer. While some collisions may be unavoidable, many can be prevented with collective effort and informed action. By slowing down, staying alert, and supporting infrastructure projects, we can significantly reduce the risks to wildlife and ourselves.

Mitigating Wildlife Collisions

One of the program’s recent successes is the completion of wildlife underpasses at the intersection of Highway 22 and Highway 390. This busy junction, a key route to Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, has historically been one of the nation’s most dangerous for moose. Thanks to the Give Wildlife a Brake program and our partners, this mitigation now provides a safe passage for animals beneath the road. Observers have already reported seeing moose, deer, and other animals using these crossings, offering hope that collisions will decrease over time.

These infrastructure improvements are direct results of community advocacy and the dedicated work of JHWF volunteers who “nature map” collision hotspots to guide where these structures are most needed.

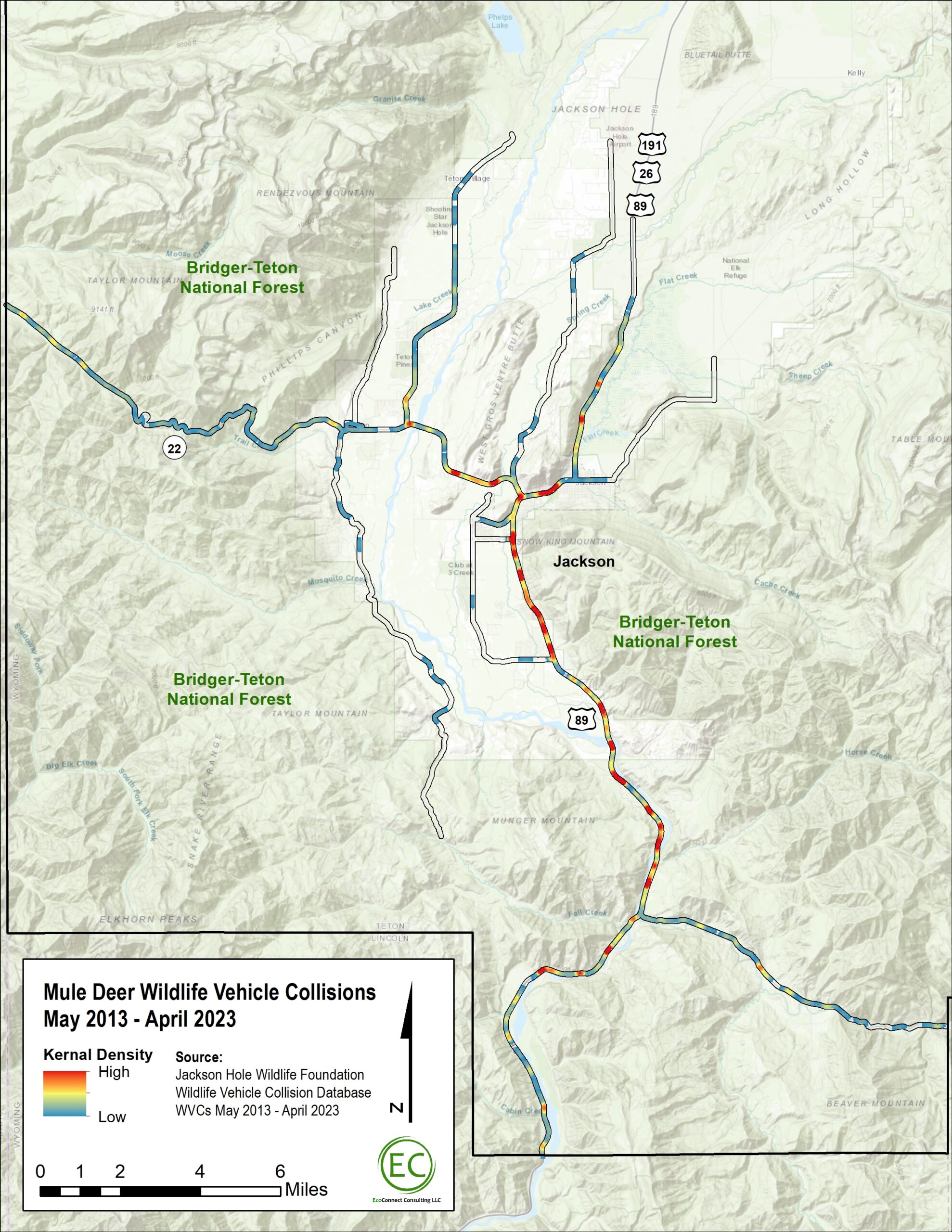

Each year, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation’s Executive Director, Renee Seidler, collaborates with Alyson Courtemanch of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and Megan Smith of EcoConnect Consulting LLC to produce the Teton County, WY and Teton County, ID Wildlife-Vehicle Collision (WVC) Database Summary Report. This comprehensive report compiles crucial data on wildlife-vehicle collisions in the region, providing valuable insights that guide efforts to reduce these incidents and protect both wildlife and motorists. By analyzing trends and identifying high-risk areas, the report serves as a critical tool for conservation planning and community safety initiatives.

As we grapple with the loss of Grizzly 399, it’s important to celebrate her extraordinary life. First documented in 2003 when she ventured beyond Yellowstone National Park into the Tetons, she became a symbol of coexistence between humans and wildlife. Over her 28 years, she gave birth to 18 cubs, including the famed foursome of 2020.

Her survival and success were a testament to her intelligence and to the efforts of a community committed to protecting wildlife. Through programs like Give Wildlife a Brake, her life was extended, allowing countless people from around the world to experience the wonder of seeing a grizzly bear in the wild.

The loss of Grizzly 399 is a profound reminder of the delicate balance between human activity and wildlife preservation. Through the Give Wildlife a Brake program, we have the tools and the opportunity to make meaningful changes that protect both animals and people.

Join us in creating a safer future for wildlife and our community. Discover how you can help reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions and make a lasting impact. Together, let’s give wildlife a brake and protect what matters most.

Written in collaboration with Bruce Pasfield, Board Emeritus, JHWF

by jhwildlife | May 10, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake

On Saturday, April 29, representatives from the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation joined Wyoming Game & Fish Department (WGFD) Wildlife Biologist Gary Fralick to survey winter deer mortality along Highway 89 south of Jackson. None of the participants could have envisioned witnessing an event that brought the poignancy of the wildlife-vehicle issue into vivid focus, but within minutes of starting the survey, they experienced an emotional interaction with one of this winter’s latest casualties.

Fralick led the targeted survey of a half-mile stretch of South Highway 89 from the Snake River Bridge at Von Gontard’s Landing north to Game Creek Road. As a group of six individuals swept through a cottonwood stand on the east side of the highway, they encountered a mule deer doe laying in the underbrush. As the group approached, the deer struggled mightily to flee but couldn’t get to its feet. Its back legs had clearly been broken in a collision with a car. How long it had been suffering there is anyone’s guess, but with the specter of starvation a certainty for an animal with two broken legs, Fralick acted quickly to humanely put the animal out of its misery.

This encounter really struck home for our participants and for Gary himself. All of our organizations recently attended the Wyoming Wildlife and Roadways Summit in Pinedale, which highlighted the biological and engineering considerations in mitigating the impacts of our roads on wildlife and increasing human safety. But this is the side of wildlife vehicle collisions (WVCs) that often goes unseen and is truly tragic. This prime age class doe deer had made it through the difficult winter we had and would likely have survived and helped the population rebound. We also witnessed a side of WVCs that only WGFD wardens and biologists and Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) highway patrol have to participate in and that is the always difficult reality of dispatching an animal, along a busy highway, something that really can never become easy, even for these trained professionals.

Mule deer doe moments after it was put down.

In reality, the life of that deer ended the moment it was struck by a vehicle. As is often the case, an injured animal struggles to its final resting place well off the shoulder of the road, where it may suffer for weeks until it starves to death. The collision may not have even been reported if it hadn’t caused sufficient damage to the vehicle. Studies have shown that up to one-half of deer vehicle collisions go unreported, so the impacts of wildlife-vehicle collisions are actually far greater than the reports on which we base a lot of our decisions.

Survey participants, moved by the power of the moment, mourn the loss of a deer that almost made it through a rough winter.

A few hundred yards from that tragic scene, the group encountered a pair of White-tailed deer carcasses that succumbed under the Flat Creek Bridge, likely after having been struck by vehicles. Those two deer, which died weeks apart in February, incidentally had images captured by a remote-sensing camera that had been placed under the bridge to study the movements of wildlife. Watching the prolonged suffering and eventual death of those deer through time-lapse photography is no easier than witnessing it first hand.

Starting in 2015, several local and regional organizations (Center for Large Landscape Conservation, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance, Teton Conservation District and Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative) began working in collaboration with WYDOT to provide pre-construction monitoring of proposed future wildlife crossings along South Highway 89/191 using remote camera sites at locations identified for their importance for connectivity in a future highway redevelopment project that will begin in 2017.

WYDOT is building six large underpasses and many smaller structures to facilitate wildlife movement, reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions, and improve highway safety. The remote cameras are monitoring the proposed locations.

Those underpasses will facilitate safe passage for deer, elk and moose as well as many smaller animals upon completion. The construction of these structures is starting this summer. Studies suggest underpasses are 80%-90% effective at reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions.

The group conducted the targeted survey to collect data that will contribute to WGFD’s knowledge about the mule deer that winter in and around the town of Jackson. Tooth samples were extracted and fibula marrow assessments were conducted on the spot to ascertain age and relative health, or body condition of the animal when it died. The group surveyed a total of one mile – a half-mile on each side of the highway. Within that stretch, 10 carcasses were observed in the ditches and wooded areas along the road underscoring the impacts of this winter on deer throughout the valley, and WVCs on this stretch of South Highway 89.

One of the last carcasses we encountered was a very old age-class doe, with a broken hind leg, wearing an eartag. We’re waiting on the results, but the tag likely came from a study looking at local movements and migrations across our roads. During that study, completed by Teton Science Schools, highway collisions was the number one source of mortality for collared deer. Since the collars have fallen off to allow researchers to collect the data stored within them, it is important that this eartag was retrieved and unsurprising that the individual was killed by a car in this stretch of road years after the study was complete.

Thankfully, construction is about to begin on the first series of underpasses on South Highway 89 and much of the carnage the group encountered on its short survey will be reduced or nearly eliminated in the near future on that stretch of highway.

In 2016, WYDOT, WGFD and local citizens recorded a total of 335 wildlife mortalities on Teton County Highways outside of Grand Teton National Park. This trial winter deer mortality survey illuminated the fact that the actual number of mortalities is likely 25%-50% higher, and it also instilled in the participants a reminder that wildlife deaths caused by vehicles often include a long, painful demise out of our view.

As construction begins on some of the first of our wildlife crossing structures in Jackson Hole, we are also grateful that Teton County is looking at its entire network of roads as it completes a wildlife-roadway master plan with the help of experts at Western Transportation Institute. Many organizations and agencies continue to discuss site-specific solutions to eliminate scenes like those witnessed on the winter deer mortality survey. All options are considered with the knowledge that various mitigation measures may be needed to address some of the complexities of Teton County’s land and roadway system.

by jhwildlife | Jan 30, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Our collective Nature Mapping observations create a long-term dataset of wildlife distribution throughout Jackson Hole. The obvious benefit is that these data provide a more comprehensive view of how wildlife use the valley. The less obvious product of the database is that it includes data that show us how human presence affects wildlife, often in the form of wildlife mortality. The most common reference source for human-caused wildlife mortality is the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation’s Wildlife-Vehicle Collision Database. It contains data derived from WYDOT and Wyoming Game & Fish carcass and crash counts, but also includes Nature Mapping observations from citizens who report roadkill to JHWF at 307-739-0968, or enter their roadkill observations directly via their Nature Mapping account. All of these records eventually are cross-checked to remove duplicates. It is an important resource, adding to our local knowledge, and helping to inform county-wide plans to find solutions that save wildlife and make our highways safer for drivers.

The Wildlife-Vehicle Collision (WVC) Database captured 259 collisions in 2015. Data for the 2015 update was acquired from the following data sources: Wyoming Department of Transportation – Carcass (118), Wyoming Department of Transportation – Crash (70), Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Observation System (33) and Nature Mapping Jackson Hole (28). In total, the WVC database contains 46 total species with mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk and moose being the most prominent species involved in WVCs.

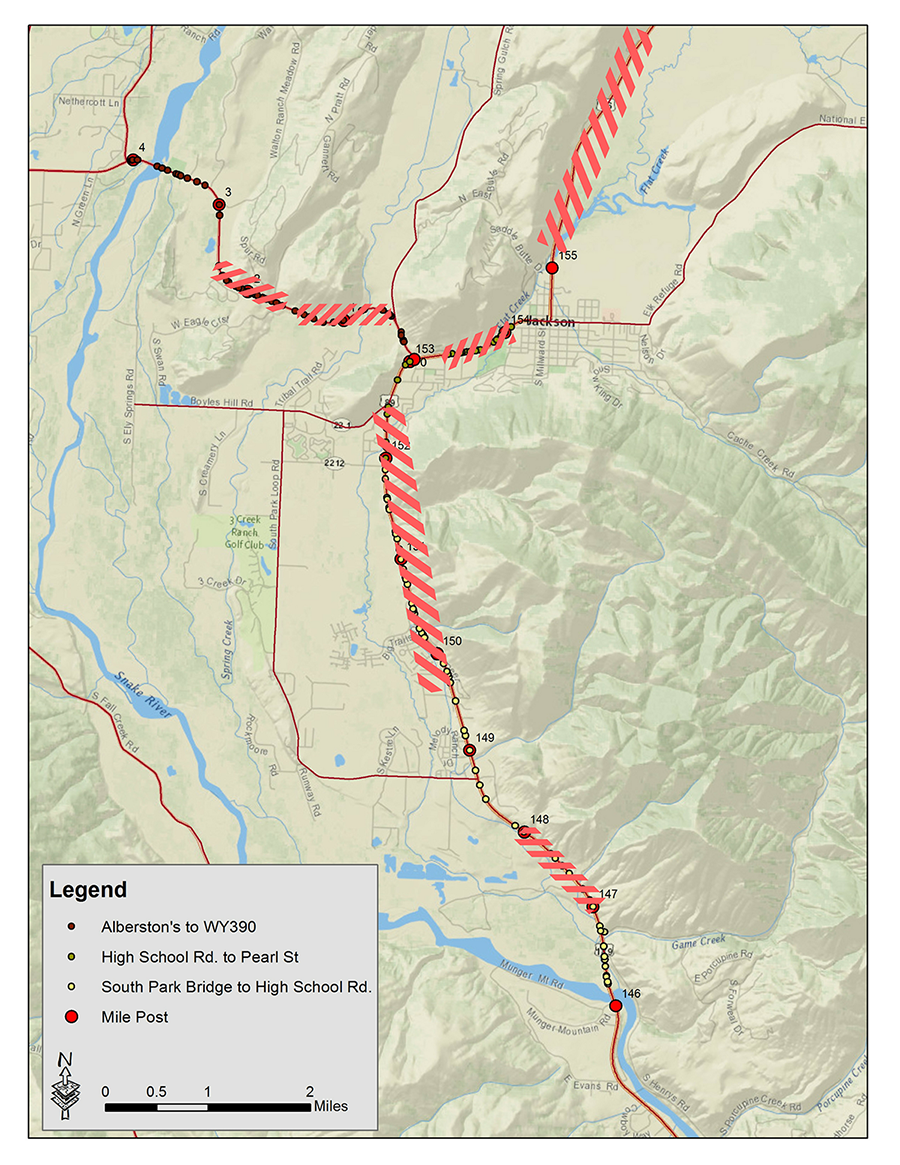

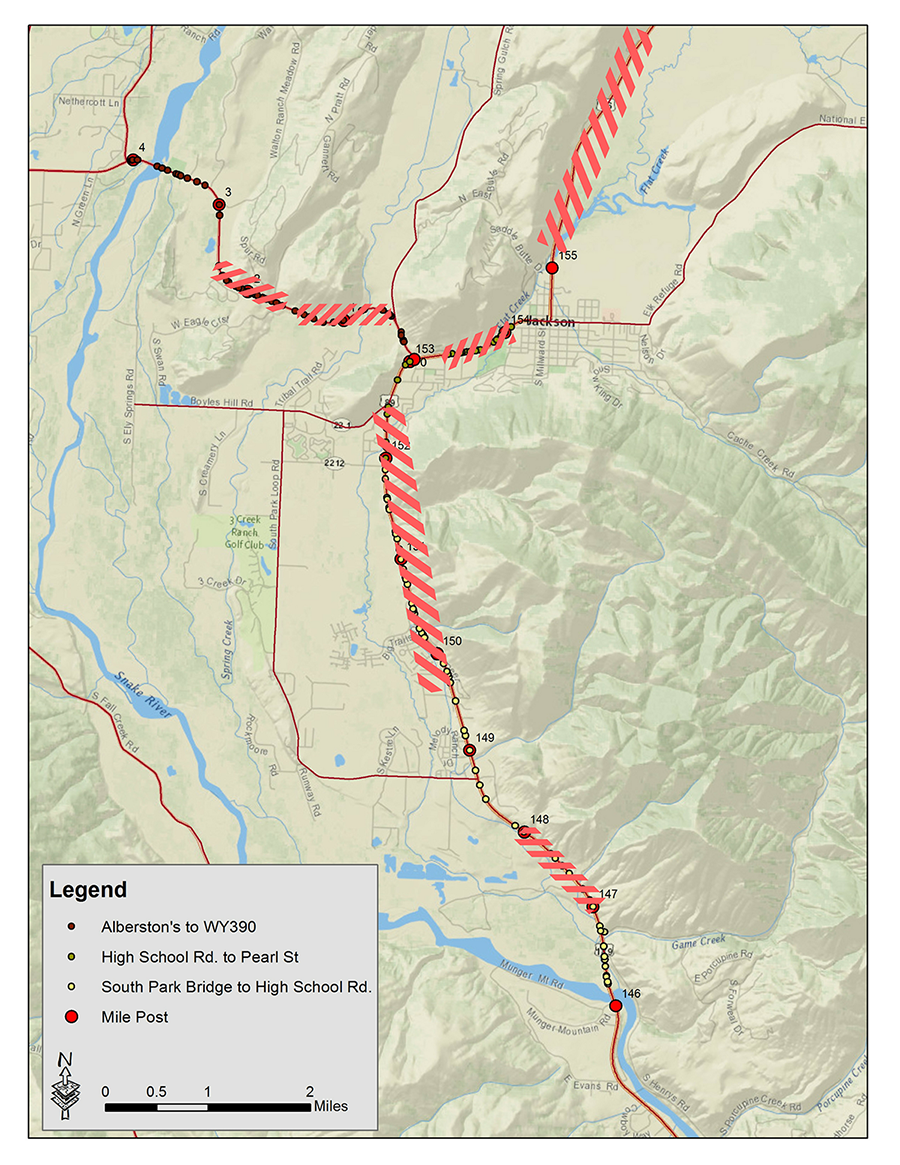

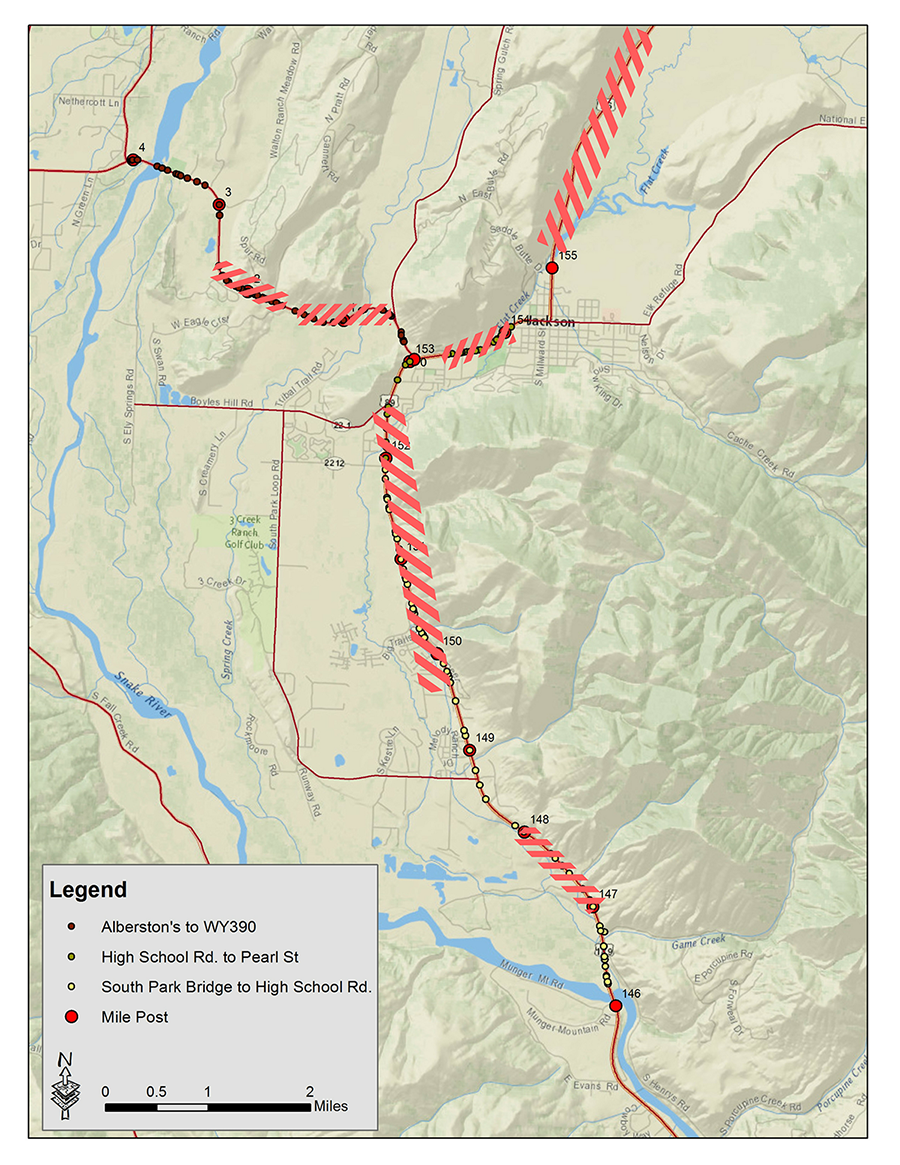

The below map shows where the most frequent collision points are on the local highway network. The highlighted areas had the highest number of collisions from 2013-2015. During this intense winter of 2016-2017, these data have helped us to pinpoint places to add emergency mitigation measures. If you see a dead animal on the side of the highway – small mammals and rodents as well as ungulates – please enter it into the Nature Mapping database, or call us at 307-739-0968 with precise location and time and our staff will enter it. We are likely underestimating the number of animals struck on the highways – certainly for non-ungulates – and our future solutions will depend on our ability to accurately capture what is happening on the roads. Thank you for your help!

by jhwildlife | Jan 27, 2017 | Blog, Give Wildlife a Brake

The Teton County Sheriff’s Office contributed two more variable message signs to a stretch of S HWY 89 as area organizations enacted emergency options to address a challenging winter for wildlife.

We have all seen that this year’s snowpack is making things difficult on wildlife. Mule deer in particular are spending more time in the town and on the roads – wherever they can find easier movement and potential forage. As they join us on the valley floor and move around where we do, the potential for conflict of many kinds increases. An obvious problem arises on our roadways, as high snowbanks both limit driver visibility and make navigation challenging for wildlife. Area organizations and agencies continue to discuss options to address the issue, some having been put in place immediately as short -and long-term strategies to reduce wildlife vehicle collisions are integrated. Here’s an update on the quick-response efforts:

Jackson Hole News & Guide article by Mike Koshmrl (Thursday, January 26)

A small herd of bighorn sheep is frequenting the stretch of N HWY 89 just north of the Dairy Queen near the town limits. Please give them ample space and time to move. Unlike deer and elk, these sheep will obstinately remain on the road.

While a county-wide master plan is in process, an array of short-term mitigation measures have been and will continue to be considered. We are grateful that a good deal of data exists on the relative effectiveness of various measures, which we use to make decisions while also recognizing the constraints of time, resources and feasibility. The planned crossings on South HWY 89 (construction set to begin next spring) will separate animals from the roadway, which data suggests is the most effective way to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions at scale. According to most research, underpasses and overpasses are 80-90% effective at reducing WVCs, while seasonal wildlife alert signage (i.e. variable mobile message signs) is estimated in the 20-25% effective range, making it an effective emergency measure and complimentary piece within a holistic WVC reduction effort. The master plan will likely include a number of mitigation recommendations to include structures, signs and speed limit adjustments to apply the most effective site-specific solutions across the valley.

What can you do now?

- Be alert and drive for the conditions. Most accidents happen at times of low visibility – dawn, dusk, nighttime or in bad weather.

- Watch for electronic warning signs. These signs are put in places where we know animals are or have recently been crossing the road frequently. They’re not just generic warnings – when you see these signs, watch carefully for wildlife.

- When you see wildlife near roadways – slow down immediately. If you see one animal cross the road, it is very likely more are close behind. Animals near the road are not waiting for us to pass by – expect them to do something unexpected, like dash in front of your car.

- In winter, wildlife often use roads to move about – it’s easier than walking through deep snow. But, sometimes they get onto a road and can’t find a quick place to get off. Give them a brake. Be patient and give them time to find a place to get off the road.

- To protect yourself and your passengers, experts advise that you should not swerve off the road to avoid hitting an animal.

- Familiarize yourself with the wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots (located here) and be even more mindful when driving there. Hint: The flashing fixed radar speed limit signs and digital message boards are located in some of these hotspots.

- Get involved with Safe Wildlife Crossings for Jackson Hole to learn about what we can do to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions as a community.

- Contact your elected officials to let them know that reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions is a high priority.

- If you see areas where snowbanks are trapping wildlife on roadways or impeding movement unusually, please don’t hesitate to call us at 307-739-0968. We work with local partners to address these issues if possible.

Additionally, if you are a Nature Mapper, record your observations of wildlife around neighborhoods and roadways. Please use the comments fields to share the activity you observe. The more information we collect about locations and behaviors during winter (all seasons, actually), the better we understand as a community how we are interacting with wildlife, with the goal of living compatibly alongside our wild neighbors.

Be especially alert in the areas highlighted on this map!