by jhwildlife | Aug 3, 2016 | Blog

Hello, moose!

There was rustling in the tall grass aside a lazy stream. A Great Blue Heron had led me here, after I had failed in a few attempts to get close to the elegant bird. I had followed its flight from take-off to landing three times now, walking quickly and quietly along the banks of these Snake River backwaters. On this third episode of the chase, the heron swooped low and banked left around some dense vegetation and, for the first time in an hour, left my view. Undeterred, I walked through the brush in the direction of the heron’s flight and zeroed in on its likely landing area. I thought I was close when I saw the rustling of the stream-side grasses. The rustling rose to what sounded like ripping and tearing, and from the vegetation emerged a moose. A clever trick by the heron to lead me to this distraction. My curious, observing eyes had found a new subject. Heron exits stage. Moose steps up to her mark.

Throughout all of this, I hadn’t seen any other people. These side channels are quiet, save for the low hush of the Snake River’s current murmuring beyond. The interactions with wildlife here are intimate. This moose and I were alone in this great theater. I watched her turn her head repeatedly to tear chutes of grass. As the early afternoon sun intensified, she slowly – very slowly – took a step into the water, and then another. And then a long pause as she stood in water that reached nearly to her belly. I could feel her demeanor change as she entered the water – its cooling effect clearly relaxing her and enticing me.

The moose enjoys cooling off on a hot, summer day.

What a joy to observe all of this. After a good while, she moved farther into the backwater and I moved from observation to reflection. What am I learning? What is she sharing with me?

I had come to this place to learn more about birds. I had my bird guide with me and a field notebook. I’ve become familiar with perhaps a few dozen birds by sight and sound this summer, and once that gate was opened, the search has become relentless and exciting. Every day seems to reveal a new bird, and what a gift that is. It’s strange to think that all these birds have always been there, but I never really noticed them.

Before the heron, and long before the moose on this day, I had identified the American Goldfinch for the first time. To those who know this common bird, it’s a fairly ordinary occurrence, however delightful. It’s such an exceptionally beautiful bird to observe. I first saw the goldfinch through my binoculars as it perched in a cottonwood tree. Glancing back and forth between my bird guide and the bird in the tree, I couldn’t identify it with

Always a thrill to see the Great Blue Heron.

certainty. But then it flew! And what a distinctive flight it is! Singing as it flies upward, then pinning its wings back for a joyous little dive. Up and down. Up and down, reminiscent of the motion we repeat when we stick our hand outside a car window and ride the air waves. I’ve since been told by an expert birder that the American Goldfinch is the “rollercoaster bird.” Perfect. What an awesome bird!

As this new world of birds has opened to me, so has my desire to record what I observe. I go back to the same place at least weekly – more often if I could – and so far I’ve never failed to see something new. I enter all of my observations into the Nature Mapping Jackson Hole database. By doing so, I contribute to our collective experience of living in this wild place. The data can be useful to local species knowledge and even to planning efforts, but maybe the greater thrill is to feel a part of a community that connects with wildlife in this meaningful way. Once I’ve committed to recording what I observe, the wonderful interactions and beautiful experiences seem to multiply many times. We share with wildlife. We share with each other. This sharing might be the essence of living in this remarkable place.

An American Goldfinch in joyful flight. A gift to us!

This valley is filled with some of the world’s finest biologists, birders and experts of every ecological field. While I’m not among these talented folks, my love for wildlife and gratitude for the beauty of a place like Jackson Hole is something that I want to share. Many people feel as I do, and Nature Mapping Jackson Hole is one place where we come together, around a shared appreciation for a place and the wild things we love.

Written by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, and enthusiastic new Nature Mapper

by jhwildlife | Aug 2, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Fence team leader Randy Reedy prepares a group of 30 volunteers for a fence removal in the Bridger-Teton National Forest on July 16.

The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation is proud to celebrate the 20th anniversary of its Wildlife-Friendlier Fencing program on August 27 at the National Museum of Wildlife Art.

When: Saturday, August 27

Where: National Museum of Wildlife Art

Cost: Free

5:30 pm: Reception in Johnston Hall (atrium), appetizers and drinks provided (complimentary)

6:15 pm: Welcoming Remarks from JHWF

7 pm: Program in Auditorium

Premiere of film “Free to Roam” by Open Range Films, which celebrates and documents the Wildlife-Friendlier Fencing Program.

Program Guest Presenter: Gregory Nickerson, Writer and Filmmaker for the Wyoming Migration Initiative

Limited capacity, so please RSVP to Kate Gersh at kate@jhwildlife.org.

The Celebration

Hundreds of volunteers have helped remove or modify nearly 180 miles of fence since the program began in 1996. We look forward to honoring many of those contributors as we celebrate our community’s commitment to wildlife. The fe

The fence program has relied on the consistent support and hands-on engagement of volunteers for two decades.

ncing program has helped to promote ways for our community to live more compatibly with wildlife. We are excited to premiere a 10-minute film titled “Free to Roam,” which captures the heart, spirit and science of the program and many of its volunteer leaders and partners. Sava and Spark Malachowski of Open Range Films created the film after spending many hours on project sites.

In addition to the short film premiere, writer and filmmaker Gregory Nickerson of the Wyoming Migration Initiative (WMI), will present “Wyoming’s Big Game Migrations: New Science Meets On-The-Ground Conservation.” Nickerson and WMI are “advancing the understanding, appreciation and conservation of Wyoming’s migratory ungulates by conducting innovative research and sharing scientific information through public outreach.” Thanks to WMI’s work, we know much more about the movement and habitat usage of ungulates. That knowledge provides a platform upon which communities can plan and implement wildlife-friendly policies and otherwise modify the impact of any human development on wildlife movement. WMI has engaged many on-the-ground partners in WMI’s work, and the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation is honored to welcome him to Jackson as we continue to create more permeable landscapes throughout the valley, using data that WMI has collected to inform our conservation strategies.

Gregory Nickerson Bio

Gregory Nickerson

Greg is a writer and filmmaker for the Wyoming Migration Initiative. He works to inform and educate the public about migration research, with a special focus on researching the human stories surrounding wildlife migration. Originally from Big Horn, Wyoming, he’s a lifelong hunter of migratory elk in the Meeteetse and Wapiti area, and has worked as a mule deer and elk guide for the Darwin Ranch in the Gros Ventre Mountains. His first documentary for Wyoming PBS chronicled the art of Thomas Moran and the photography of William Henry Jackson on the 1871 Hayden expedition to Yellowstone, which led Congress to set aside the area as America’s first national park. In 2013, he won a Mid-Atlantic Emmy as an associate producer with History Making Productions for a film about the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia. From 2010-2015 he was a contributor and staff journalist for the online news site WyoFile.com, where he covered Wyoming state government and the University of Wyoming, including several stories about UW’s migration research on mule deer and bighorn sheep. Greg holds a M.A. in history of the American West from the University of Wyoming, and a B.A. magna cum laude from Carleton College.

Wyoming Migration Initiative Director and Cofounder Matt Kauffman releases a tagged mule deer.

by jhwildlife | Jul 8, 2016 | Blog, Wildlife Friendlier Landscapes

Join Us for Our August 6th Fence Project:

On August 6th, we are returning to the Gros Ventre to Crystal Creek, to remove more than one mile of barbed wire fence on Bridger Teton National Forest land. The project is average in difficulty (6 on a 1-10 scale), with most of the work on rolling terrain after a moderate hike up to the fence line. Please join us!

We will meet at three car pool sites:

- Home Ranch Parking Lot (north side) at 8:00 a.m.

- Gros Ventre junction at 8:15 a.m.

- Kelly Warm Springs at 8:30 a.m.

We will carpool from these sites to project. We plan to work from 9:00 a.m to 2:00 p.m. and half-day (morning) is welcome, as well.

We will provide water and snacks. Please bring your own water bottle or hydration packs. We will provide water and Gatorade to fill your bottles, and some granola bars for a snack. Additionally we will take a mid-day lunch break. Please bring your lunch.

You should wear layered clothes, long pants, sturdy shoes and bring a rain jacket in case of storms. Sun or eyeglasses are a MUST for working with barbed wire. Sun protection (hat & sunscreen lotion) is also recommended, and will hopefully be necessary! We also recommend that volunteers check the status of their tetanus shots, in case of scratches from the old fencing material. We will provide work gloves, tools, and detailed instructions.

Please RSVP to jhwffencepull@gmail.com if you plan to attend and let us know at which meet-up point you will join us (1 of 3 locations listed above). You can also send questions to this same email address.

30 Volunteers removed 1 mile of barbed wire at Crystal Creek on July 16th.

by jhwildlife | Jun 23, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

In June, JHWF was visited by a group of conservation professionals from Argentina, Russia, Iran, Sierra Leone, Malaysia, South Africa, Morocco, Sri Lanka, Oman and Zimbabwe. This group was supported by the International Visitor Leadership Program of the U.S. Department of State and hosted by our friends at the Wyoming Council for International Visitors.

Traveling with the objective of assessing U.S. efforts to protect biodiversity, JHWF was pleased to spend an hour with our new colleagues talking about wildlife-friendly communities. There was great interest in learning more about the citizen science effort throughout the valley and how the Nature Mapping program was designed. Citizen science is not (yet) a strong practice in many other countries, but there is growing interest to engage the public in conservation science. We said that one of the keys to launching a successful citizen science effort is to have a “champion,” such as the admired and beloved Bert Raynes, to inspire an initial following.

A visiting biologist from Morocco inquired about the bluebird nest boxes he observed along the Elk Refuge fence. “I noticed more tree swallows than bluebirds as we drove into town,” he said. His observation concurred with our findings in recent weeks, as many of the Mountain Bluebirds and their fledglings had left the boxes, though a few remain. While we delighted in the fact that nearly every representative expressed interest in introducing a variation of Nature Mapping in their country, we also couldn’t help but recognize the common joy we all derive from our interactions with wildlife – a universal bond.

It was an interesting discussion comparing and contrasting our conservation challenges and subsequent efforts around the world. While our working contexts might differ in terms of political, social and economic influences, a consistent thought existed amongst our diverse group – the belief that by removing or reducing barriers we humans have created (obsolete barbed wire fencing, for example), we can moderate our impact on wildlife and live more compatibly within a healthy environment that sustains all life.

by jhwildlife | Jun 10, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Bison Chronicles

By Ben Wise

With recent media coverage of bison populations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (i.e. Montana bison reduction program, bison calf abductions in Yellowstone National Park and the recent adoption of bison as the National Mammal), it seemed fitting to review the origin of the bison population in Jackson Hole. Bison are native to Jackson Hole but had been extirpated by as early as 1884 when homesteaders arrived in the Jackson Valley. The last remaining bison population in the western United States occurred in Yellowstone National Park and by 1902 numbered only 23 individuals.

In 1948, Laurance S. Rockefeller’s Jackson Hole Preserve cooperated with the New York Zoological Society and Wyoming Game and Fish Commission to establish a fenced wildlife park near present day Moran. The Jackson Hole Wildlife Park served to attract visitors to the Jackson Hole National Monument (now Grand Teton National Park), as well as serving as a scientific research center and a place where visitors could easily view wildlife. The creation of the Wildlife Park was quite controversial and led to the resignation of renowned Olaus Murie from the board of the Jackson Hole Preserve.

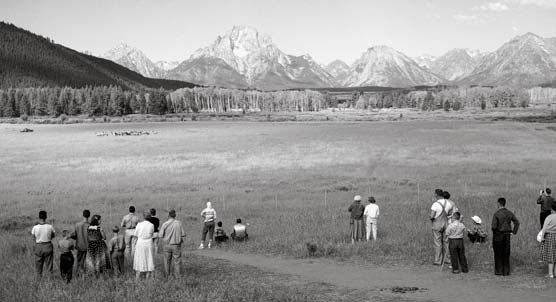

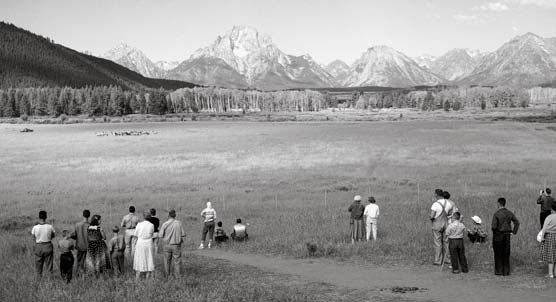

Jackson Hole Wildlife Park photo credit: Grand Teton National Park

Shortly after the Jackson Hole Wildlife Park’s creation, 20 bison were relocated from Yellowstone National Park to fenced enclosures within the park. Management of the Park was primarily the responsibility of the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission until the expansion of Grand Teton National Park in 1950. At that time, management of the Park began shifting to the National Park Service. Throughout the 1960s, management actions were coordinated with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and included winter-feeding, capturing bison that escaped (which occurred several times annually), and routine brucellosis testing and vaccination. Herd size varied from 15-30 until 1963 when brucellosis was documented in the herd. Thirteen adults were removed from the herd, leaving just four yearlings. The yearlings, which had been vaccinated, were retained, along with five new calves that were also vaccinated.

In 1964, 12 certified brucellosis-free adults (six males and six females) were obtained from Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota, bringing the total number to 21. By 1968, the population had declined to 11 adults (all testing negative for brucellosis) and four or five calves. Later that year, the entire herd escaped the confines of the Wildlife Park. Efforts to recapture the bison were unsuccessful and the decision was made to let the herd roam free.

From 1969-1976 the population averaged 14 animals. The bison wintered within Grand Teton National Park until 1975, when they moved to the National Elk Refuge. By 1980, bison were taking advantage of the supplemental feed intended for elk. The bison readily adapted to the situation, as they had no trouble displacing elk from the feedlines, and subsequently, the population started to grow rapidly. The population peaked at approximately 1,200 animals before a hunt was established on the Refuge in 2008. Currently, the population is estimated at 666 animals. The objective for the population is 500. Refuge personnel have provided separate feedlines for bison on the northern end of the Refuge near McBride since 1984 to minimize conflicts between bison and elk. Jackson bison winter primarily on the National Elk Refuge and summer almost entirely within the boundary of Grand Teton National Park.

About Ben Wise:

Ben Wise is a member of Nature Mapping Jackson Hole Scientific Advisory Committee and is the Brucellosis-Feedground-Habitat Biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.