by jhwildlife | Feb 7, 2020 | Blog

By Aly Courtemanch, Wildlife Biologist | Wyoming Game and Fish Department

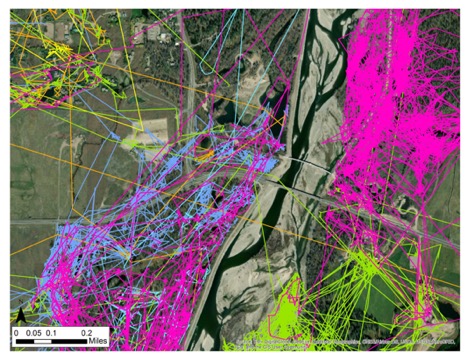

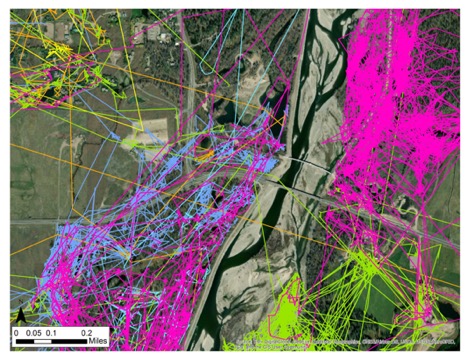

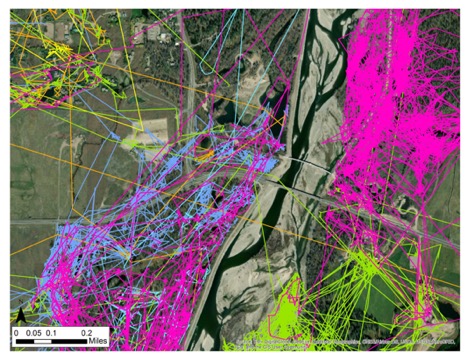

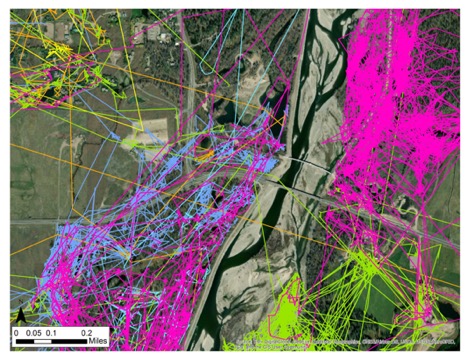

Collared moose GPS locations in the vicinity of the Snake River Bridge and Highway 22/390 intersection from March 2019 – January 2020. Each color corresponds to an individual collared moose. The GPS collars collect a point every 30 minutes.

Moose are one of the most beloved wildlife species by our community. During the winter, they become more easily observable when they migrate down to low elevations and are often seen right in our neighborhoods and backyards. However, living amongst humans and our development can be dangerous too. The number of moose-vehicle collisions on roads have steadily increased in recent years in Teton County.

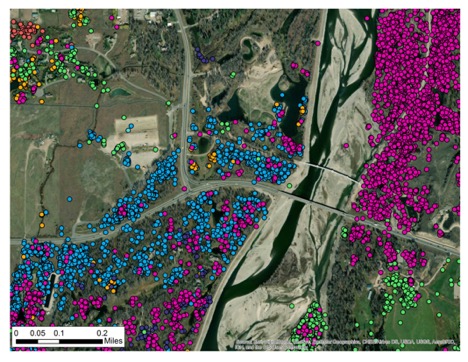

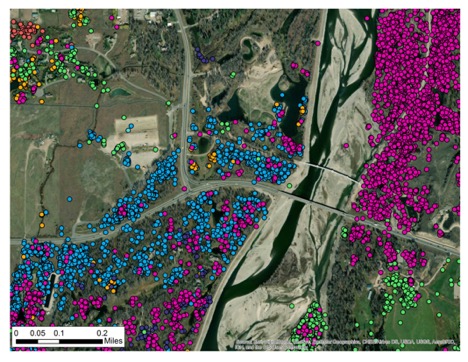

For this reason, the Wyoming Department of Transportation and Wyoming Game and Fish Department partnered in 2019 to learn more about when, where, and how often moose cross roads. In March 2019, we darted 10 cow moose within 3 miles of the Snake River Bridge and Highway 22/390 intersection and fit them with satellite tracking collars. These collars are programmed to collect a GPS location every 30 minutes and will stay on the moose for 2 ½ years, at which point they will automatically detach and drop off. The collars upload their GPS locations every 2 days to a satellite, which then sends the locations to an email account where we can download them. This technology allows us to get real-time data on moose movements and be alerted to possible mortalities.

Kate Gersh, Associate Director Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, sits with an anaesthetized cow moose while she wakes up.

This is the first time that moose have been collared in this area so we are learning new and very interesting things about their movements. We have learned that four of the 10 moose are migratory, meaning that they moved from their low elevation winter ranges where they were collared to high elevation summer ranges. One of the collared moose spent the summer in Grand Teton National Park in Open Canyon and Death Canyon. The other migratory moose spent the summer in Phillips Canyon and Teton Pass. Six of the 10 moose are resident, meaning that they used generally the same areas in the summer and the winter. Resident moose mostly spent the summer on West Gros Ventre Butte, around the Wilson area, and along the Snake River, Fish Creek, and Fall Creek.

We have also learned that some moose cross roads a lot, whereas others cross very infrequently. Two moose have only crossed Highway 22 or 390 once or twice during the past 10 months. Other moose have crossed 27, 34, and 67 times! So far, only one collared moose has died. She died of unknown causes but had not crossed any roads while she was collared, so her death was not caused by a vehicle collision. The moose collar data has already provided important information about where wildlife underpasses should be located as part of WYDOT’s Snake River Bridge replacement project, which is expected to start construction in 2022.

Collared moose movements in the vicinity of the Snake River Bridge and Highway 22/390 intersection from March 2019 – January 2020. Each color corresponds to an individual collared moose. The lines shown on this map connect the 30 minutes points seen on the previous map.

This project has received a HUGE amount of support from our community! In addition, many new funding partners have contributed money this year to expand this study. Thanks to this help, we plan to dart and collar eight more cow moose in March 2020 and partner with other researchers to study how diseases and parasites (winter ticks) are affecting moose.

I want to extend a huge thank you to all of the private landowners who allowed us access to their property to dart and collar these moose! Thank you to our funding partners: Wyoming Department of Transportation, Teton Conservation District, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, U.S. Geological Survey, Teton County, and Veterinary Initiative for Endangered Wildlife.

by jhwildlife | Jan 24, 2020 | Blog

By Jon Mobeck, Executive Director |

The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation had a terrific year in 2019, making meaningful contributions to our wild community in a variety of ways. Our work to make roads safer for people and wildlife, which began at our founding 26 years ago, continued as we joined partners in supporting a successful ballot initiative that resulted in a $10M investment in wildlife crossing infrastructure. Our annual Teton County Wildlife-Vehicle Collision Report, along with the many graphs, maps and infographics we created to enliven these data, illuminated the impact of our roads on wildlife and provided an essential tool to decision-makers.

Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation volunteers and staff completed 21 fence modification or removal projects in 2019.

In the past year, with 300 Wildlife Friendlier Fencing volunteer days logged over 21 projects, we removed or improved 14 miles of fences in Teton and Sublette County, WY. Over the past four years alone, volunteers have collectively contributed more than 1,000 days in the field to make 28 miles of fence more conducive to safe passage for wildlife.

Also this year, our team organized 20 Snake River Float Surveys from May to September during which we recorded more than 7,000 wildlife observations. We spent more than 1,000 hours in the field capturing 619 birds and banding 372 of them to contribute data toward a multi-decade bird research project. In the 16th season of our Mountain Bluebird Nestbox Project, our volunteers monitored 112 boxes as we gathered more data on the least-studied member of the bluebird family. Nearly 100 volunteers turned out to record moose observations on Moose Day 2019, providing valuable data to the Wyoming Game and Fish Department on one of Jackson Hole’s most iconic, and perhaps vulnerable, species.

The best thing about all of these accomplishments is that they are the product of an engaged community. The JHWF team has the honor of helping to coordinate and plan projects, but nothing happens until passionate individuals pitch in. Many of the hundreds of JHWF volunteers have been there since the beginning in 1993. Others have more recently joined the “JHWF family”.

Securing $10 million in funding for future wildlife crossing solutions on last year’s SPET ballot was a major win for the wildlife conservation community.

After four years as the Executive Director of JHWF, I now have the opportunity to embark on a new adventure in a new place. While setting off in a new direction is exciting, I’m also grateful for a pause that allows me to reflect on the experiences along the trail that led me here, and express my gratitude to the people who have made this work so rewarding for me. The job of Executive Director of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation is one of the best jobs on the planet. The daily interaction with the great people of this community, and the daily interactions with wildlife, together comprise an exceedingly rare privilege.

Thank you to every board and staff member, to every volunteer and donor, to every agency and organizational partner, to every engaged community member, for being a part of something that I believe to be truly special. The work of JHWF is vital, conducted in a way that builds grassroots support for meaningful improvements to the landscape for wildlife. If a “land ethic evolves in the minds of a thinking community” as Aldo Leopold suggested, then Jackson Hole’s passionate community members form a fertile landscape, and JHWF’s deep roots have supported the growth of a forest of beneficial actions.

During the next few months, JHWF will seek to find a new Executive Director, and I will continue to fulfill my responsibilities until I can hand them to a new person, which I will be honored to do. Few places in the world retain the riches of wildlife that we enjoy here, and few opportunities are as good as this one to make a difference with a wide-ranging family of active wildlife enthusiasts and advocates.

I would strongly encourage interested people to learn more about the position and apply at https://jhwildlife.org/about-us/jobs-and-internships/

To the community of wildlife supporters of all kinds, I offer my thanks and appreciation.

Onward!

by jhwildlife | Jan 22, 2020 | Blog

By Kyle Kissock |

Do slower speeds reduce the chance of a wildlife-vehicle collision?

While the short answer is yes, the longer answer is likely a bit more complicated.

In winter, ungulates like mule deer cluster on the low-elevation buttes around town. Driving the posted speed can help reduce your chances of a collision with an animal.

An article in a recent Jackson Hole News and Guide highlighted the research of biologist Corinna Riginos, who was contracted by the Wyoming Department of Transportation to study the effects of reduced nighttime speed limits on wildlife-vehicle collision (WVC) rates on high-speed roadways.

Riginos’s results indicated that site-specific, nightly speed limit reductions from 70 mph to 55 mph failed to decrease WVCs.

The reason? Despite lower posted nightly speed limits (and in some cases increased enforcement) drivers decreased their average vehicle speeds only 3-5 mph.

This decrease in speed was likely not enough to compensate for the fact that vehicles traveling through “high-speed” study sites were moving relatively fast to begin with.

As the vast majority of WVCs occur at night, drivers involved in collisions likely still “outran” their headlights, a phenomenon that becomes increasingly hard to avoid (even for attentive drivers) as vehicle speeds exceed 35 mph.

However, it’s important to note that this study focused on a specific type of road; high-speed, two lane highways, and does not mean that slower speed limits are ineffective at preventing WVCs.

Rigino’s recent study showed that on high-speed roadways (70-80 mph) nighttime speed limit reductions had little effect to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions

As Riginos points out, research indicates that deer-vehicle collisions in zones with permanent speed limits of 65 mph were over 60% more likely to occur than deer-vehicle collisions in zones with permanent speed limits of 55 mph. In these areas, even a 10 mph decrease made a significant difference.

What about nightly speed limits in Teton County?

Although it does get harder to avoid WVCs at night as you “outrun” your headlights, reducing your vehicle speed still means increased reaction time as a driver.

Currently, ungulates in our valley are residing at low elevations and spending time on or near roadways where travel is easier than wading through the deep winter snow pack.

It’s on these town and county roads, where speed limits are relatively low to begin with, that driver behavior can have an out sized impact on avoiding collisions with wildlife.

For example, reducing your speed from 40 mph 30 mph on Broadway (in the 30 mph posted stretch) likely has more of an impact on collision avoidance than if you were to reduce your speed from 80 mph to 70 mph on, say, Interstate-80.

Moose-Wilson Rd, N. Highway 89 in Grand Teton National Park, and south of town near Rafter J are examples of where recent WVCs have occurred, and where abiding by the speed limit at night (it is the law after all) can truly safe a life.

By modeling good driver behavior, those of us who care deeply about wildlife can set examples for the rest of our community to follow!

by jhwildlife | Jan 9, 2020 | Blog

By Kyle Kissock |

What birds come to mind when you think of species that are ‘seasonal residents’ of Jackson Hole?

While you’ll likely consider any number of summertime breeders, Osprey, Mountain Bluebird, or vibrant Yellow Warblers, there are a select few species which expand ranges south into Jackson during winter.

These ‘winter residents’ usually depart our valley by springtime for breeding grounds farther north.

This article profiles five of these unique, winter-residents, which Nature Mappers can be on the lookout for now, as the snow flies!

Northern Shrike (Click for Sightings Map)

The Northern Shrike is a predatory songbird which breeds in polar regions. It expands its range south during the winter, where in Jackson Hole, it replaces the Loggerhead Shrike (a summertime breeder) as the resident Shrike species in the valley. Nature Mapping submissions indicate Northern Shrikes are seldom seen in the valley after the first week of April, which is when this species returns to its northern breeding-grounds. Our FOY (First of Year) Northern Shrike was Nature Mapped on December 16, 2019.

Northern Shrikes are generally solitary and are often spotted perched on shrubs or fences in relatively open country. Nature Mapping observations indicate you should look for them in the willows along Moose-Wilson Road and the Gros Ventre during the winter.

Rough-Legged Hawk (Click for Sightings Map)

Photo Credit: Tom Koerner, USFWS

The Rough-Legged Hawk is a tundra-breeding buteo which migrates as far south as Texas for the winter. Although Nature Mappers report Rough-legged Hawks in Jackson Hole throughout the winter, sightings tend to be more regular in our valley from mid-October to early December, and then again in the spring. This is likely due to the maximum snow cover Jackson Hole receives mid-winter, as deep drifts or thick ice accumulation can prevent Rough-legged Hawks from reaching their subnivean food source (generally rodents) under the snowpack. Teton Valley is a great place to consistently observe Rough-legged Hawks all winter. The FOY sighting for this species was Nature Mapped on November 30, 2019 by Frances Clark. Our data indicates this species begins to depart the valley by mid-March.

A medium-sized hawk with dark brown “shoulder patches,” dark wing tips, and a dark belly, Rough-legged Hawks prefer open country and are seldom found in conifer forests. Search for them on telephone polls near Kelly Warm Springs.

Bohemian Waxwings (Click for Sightings Map)

Bohemian Waxwings are a highly nomadic species; according the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Unlike most other songbirds, they don’t hold breeding territories and their presence any given year can be sporadic. When they expand their range south in the winter, they travel in large flocks in search of fruiting plants, frequently mixing with American Robins or with Cedar Waxwings, which unlike Bohemian Waxwings breed in Jackson Hole and can be spotted here all year. Bohemian Waxwings are seldom seen in the valley after the first week in April. Nature Mappers are yet to report a Bohemian Waxwing sighting in 2020, however, this species often appears in our valley as early as the first week of November.

Look for a chunky, dark, medium-sized songbird likely traveling in a large flock. To differentiate a Bohemian Waxwing from a Cedar Waxwing, look for white on the wings and diagnostic rust-colored patch under the tail. Search for marauding flocks Bohemian Waxwings in town on Crabapple trees.

Common Redpolls (Click for Sightings Map)

The Common Redpoll is a great example of what is considered an “irruptive” species, meaning it is not uncommon for it to irregularly expand its range into areas where it isn’t usually found (likely in search of food). Frances Clark reported multiple “irruptions” of Common Redpolls in Jackson in recent years, including 2016. Although Common Redpolls are rarely Nature Mapped, at least one Nature Mapper has sighted this species in all but one year since 2011. This species has yet to be recorded by nature mappers this winter. Common Redpolls eat small seeds and are especially attracted to thistle and nyjer feeders, so keep your eye out if you have feeders in your yard . . . our Nature Mapping data shows this bird regularly shows up in town and developed areas.

Look for a siskin-like songbird with a puffy red-chest and a bright red-cap, likely in a flock. Any feeder in Jackson Hole could attract a Redpoll during the right conditions.

Snow Bunting (Click for Sightings Map)

Our Nature Mapping database contains only 13 reports of Snow Buntings dating back to 2010. Like many of our other winter visitors, this species breeds on the tundra of the high Arctic and expands its range south in the winter. Snow buntings occur exclusively in grassland areas, which in our valley are largely inaccessible during the winter. Teton Valley may be the best place to go to encounter this species, but keep your eyes open when you’re driving out to Kelly or on the National Elk Refuge. The most recent Nature Mapping report of a Snow Bunting was submitted by Tim Griffith on March 4, 2018. Nice spot Tim!

Look for a small, white and black songbird with rusty facial markings, likely traveling with multiple individuals.

Special thanks to Bernie McHugh of the Jackson Hole Bird and Nature Club for his help with his article.

by jhwildlife | Nov 8, 2019 | Blog

By Lead Nature Mapping Volunteer Frances Clark

Late fall, early winter is a time of adjustment for wildlife, as well as us. The increasing cold and diminishing food in November encourages movement of species. Many warm bodied critters have left the valley, while others stay here. Winter residents must hibernate, or they must balance their energy budget: conserving their energy use by resting in warm, protected locations or adding to their energy stores by moving and finding sufficient food.

Raccoon tracks in the snow from Wilson, Wyoming.

Some small mammals disappear but others are active. Look for any chipmunks, mice, or voles that may still be seeking seeds, fruits, and invertebrates. They will soon hibernate or go into a torpor. Record these stalwart individuals if you see them. Red squirrels stay up and about to defend their cone stashes vociferously. At night skunks and raccoons are roaming for food and then hunker underground or around buildings for warmth. Fox and coyotes are padding along trails and through fields looking for all the above as their main meal. Long- and short-tailed weasels are turning white and also darting about for prey. Have you seen a bear as a last of year (LOY) entry?

Many of the above critters are usually invisible to us; however, with a skim of snow their tracks prove they are here. Some, such as snowshoe hares, are actually best noted in winter. Pull out your winter-tracking field guides, find a 6-12” ruler to measure the footprint size and stride, and determine whose prints cross your path. Under “activity” enter “animal sign: tracks, scat”, under “notes” your ID details. If possible, attach a photograph of the prints with a ruler for scale (a new feature on our data entry form!) to help our biologists verify your entry. It is fun to record the mysterious dramas going on in our neighborhoods and wild places.

Large mammals are shifting venues, too. Watch for elk and deer crossing roads and grazing in pastures. Where are they now? Keep an eye on the buttes to see if the mule deer are coming back to their traditional winter range, or have the summer fires on East Gros Ventre Butte caused them to shift elsewhere? Where are the bison hanging out? Bighorn sheep are coming into the Elk Refuge. Can you record their “territorial” or “breeding” activity in the next few weeks? And moose: are they bunching up at Antelope Flats? What are they eating? They often prefer antelope bitterbrush at this time of year.

Bighorn sheep can currently be spotted on Miller Butte. Photographer Credit: Mark Gocke

Look and listen for birds*. Trumpeter swans are migrating down from Canada, adding numbers to our resident population. Where are they resting/loafing, and which routes are they flying? See if there is a tundra swan mixed in. Which ducks are feeding in open ponds and streams? Remember, some may be in “basic” (e.g.. non-breeding or dull winter) plumage—an ID challenge. Grouse—ruffed and dusky–are in the forests; and nuthatches, juncos, golden-crowned kinglets, and chickadees forage in mixed flocks. The corvid family: ravens, crows, Canada jays, Steller’s jays, and Clark’s nutcrackers often come down from higher elevations and into town when there is deep snow and cold—they are smart. Cooper’s hawks take advantage of birds congregating at bird feeders. Use your binoculars to spy soaring rough-legged hawks or fleeting groups of snow buntings and horned larks in open grasslands. Or find kettles of ravens and eagles over a gut pile.

There is plenty to Nature Map in Jackson Hole these next few weeks. The new entry form makes it easier than ever. Your sightings are extremely important to indicate which wildlife habitats are essential for winter survival. Keep on mapping! Thank you.

*Note: The JH Bird and Nature Club will be hosting a “Winter Bird ID” program December 10th. See the Calendar of Events below for details.