By the JHWF Staff As wildlife conservation professionals, we remind ourselves to celebrate the successes. Sometimes we get so wrapped into understanding and mitigating the challenges facing wildlife that we feel frustrated. In these moments, it is sometimes in our...

Our Moose Mission: The Importance of Moose Day

Moose Day: Contributing to Moose Science

Every winter, moose in Jackson Hole face extreme challenges. They rely on shrubs like willows and aspen for food, but deep snow and cold temperatures make survival tough. Unlike deer or elk, moose don’t migrate long distances to escape snowpack. Instead, they use their long legs and specialized hooves to navigate deep snow and access food. However, energy conservation is crucial—any unnecessary movement could cost them valuable resources they need to survive the winter.

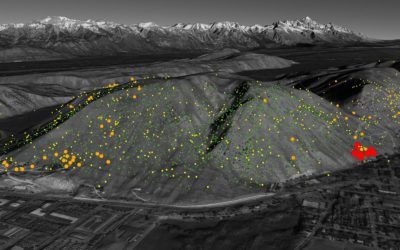

To better understand how moose are faring during this critical time, the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF) hosts its annual Moose Day. Volunteers from the community gather data to track moose locations, signs, and winter behavior. This data is part of Nature Mapping Jackson Hole, a program designed to give everyday people a role in local wildlife conservation.

Our Moose Mission: A Collaborative Effort

Moose Day is a collaborative effort between JHWF, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD), Grand Teton National Park, and the Bridger-Teton National Forest. Together, these organizations focus on collecting critical data about moose to monitor population trends and habitat use in Jackson Hole.

Certified citizen scientists and trained volunteers play a central role in Moose Day. Teams of two or three are assigned parcels to survey, often near private lands or developed areas where WGFD biologists face logistical challenges. Volunteers document moose sightings, tracks, scat, and browsing evidence. This collaborative approach allows for more comprehensive data collection, filling gaps that would be difficult for professional biologists to cover alone.

The data gathered during Moose Day is part of the Nature Mapping Jackson Hole program, which builds a long-term database of wildlife observations. By tracking moose and other species year-round, this community science initiative empowers local residents and visitors to contribute to conservation in a meaningful way. The data supports wildlife managers, researchers, and land-use planners in making informed decisions that protect wildlife and their habitats.

Moose Day is more than just data collection—it’s a rewarding experience that fosters a deeper connection to Jackson Hole’s wildlife and wild lands. It brings the community together for a shared purpose and highlights the importance of conserving the valley’s unique ecosystem.

Why Moose Day is Important

Moose populations in Jackson Hole have been declining due to habitat loss, warming winters, increased human activity, and disease. Winter is a particularly critical period to monitor because it’s when moose are most vulnerable. Deep snow can trap them in small areas, limiting their ability to find food and avoid predators. Meanwhile, access to key resources like willow flats or aspen groves becomes vital for survival.

The data collected during Moose Day helps:

- Identify areas where moose are wintering successfully.

- Track population trends over time.

- Inform land management decisions to protect critical moose habitats.

By participating in Moose Day, volunteers play a direct role in wildlife conservation efforts, helping researchers and land managers better understand and address the challenges facing this iconic species.

Moose Day 2025:

Saturday February 22th

JHWF’s Blogs

Won’t You Join us in Celebration?

Beaver Project

By Jeff Burrell and Hilary Turner Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation is excited to announce a new partnership with beaver researcher and hydrologist Jeff Burrell and a new project for interested Nature Mappers – Beaver Project! In Beaver Project, Nature Mappers will...

A Weekend on the Wind River Indian Reservation

By Charlie Brandin The great debate - bison or buffalo? I spent last weekend at the Wind River Indian Reservation learning how western science (which classifies the animal as bison) and indigenous knowledge (which classifies it as buffalo) come together for an...

Nature Mapper Profile: Meet Kathy O’Neil and John Norton!

By Hilary Turner As Nature Mapping Jackson Hole nears its landmark 1000th certified Nature Mapper, I thought it would be fun to write an article featuring a couple of newer Nature Mappers who were just trained in the last year. Many of you have participated in Nature...

Meet our Summer Bird-Banders

This year, Vicki Morgan and Kevin Perozeni will head up our MAPS bird-banding stations at Boyle's Hill and the Kelly Campus of the Teton Science Schools. Vicki will be returning for her third summer in a row, while Kevin will be joining us for the first time! Vicki...

Nature Mapping Summer Challenge with Maven® Binocular Giveaway

Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation is proud to partner with Maven® Outdoor Equipment Company in a Nature Mapping Summer Challenge! Maven® has graciously donated a pair of C.1 10x42 binoculars (MSRP $425) to the JHWF to be given away to a Nature Mapper who completes the...

Spring Emergents and Arrivals: First of Year (FOY)

Nature Mapping Enews – April 4, 2022 – Written by Frances Clark “I saw my first robin!” “I saw bluebirds!” “Did you hear the sandhill cranes the other day?” “No, but I heard meadowlarks up in Antelope Flats.” “The bears are out.” “Have you seen an...

Moose Day 2022

By Frances Clark A valiant cadre of over 95 volunteers ventured out on a frigid morning to scout for moose with great accomplishment. The latest count, still to be verified, is 94 moose. This compares well with Moose Day 2021 when 109 volunteers recorded 106 moose....

Thanks for a Great Hosted Moose Day!

We'd like to extend a special thank you to all the new participants and visitors who joined us at Rendezvous Park in sub-zero temperatures on the morning of February, 26th for Hosted Moose Day. While only one of our hiking groups spotted a moose, it's important to...

Where does the chicken cross the road? Thoughts on the things we wouldn’t know without your help

By Dr. Hannah Specht, University of Montana Citizen scientists, the world round, invest in data collection on the understanding that this effort will contribute to expanding knowledge and the hope that it will move us forward. The timeline for knowledge expansion, and...

JHWF Receives Bear Wise Jackson Grant

Did you know that Teton County experiences an average of 71 human-bear conflicts per year? Sadly, in 2021 alone, six grizzly bears were euthanized because of human food-conditioning. Now more than ever, we believe bears need our...

Grand Teton National Park’s Bird Program: a Collaborative Approach to Preservation

By John Stephenson, Grand Teton National Park wildlife biologist While people flock to Grand Teton National Park for its spectacular wildlife often hoping for a glimpse of an elusive wolf or grizzly, most visitors are all but guaranteed sightings of remarkable bird...

Why Should I Care About Winter Range?

By Morgan Graham, Teton Conservation District Growing up in Pennsylvania, I was not intimately familiar with the concept of winter range. Seasonal shifts were marked by hundreds of Canada geese gorging on leftover corn and soybeans. Over time more and more of those...

Beavers: We need them but they need our help

By Jeff Burrell - Hydrologist and former director of the Wildlife Conservation Society Northern Rockies Program. Cover Photo from Neil Herbert (Yellowstone National Park) There’s been a growing appreciation of the important role beavers can play in creating and...

Protect our Bears by Keeping Them Wild

Holy cow. I am impressed at the boldness of bear 399. She is a survivor and is imparting this skill and resourcefulness on her four cubs. How did we get from the near extirpation of grizzly bears to bears walking through Jackson? The incredible foresight of the...

Meet the Neighbors to Nature Volunteers

By Hilary A. Turner, JHWF Neighbors to Nature (N2N) is a community science project supported by the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF) and our partners – The Nature Conservancy of Wyoming (TNC), Friends of Pathways (FOP), and the Bridger-Teton National Forest...

August is for the Shorebirds

Hilary Turner | Nature Mapping Program Coordinator Fall migration is a fun time for birders and it is the only time of year we Wyomingites get to examine many members of one of my favorite groups – the shorebirds. These members of the order Charadriiformes can be...

Help Keep Bears Wild and People Safe on Togwotee Pass

For Immediate Release April 25, 2025 Agencies Call Upon the Public to Help Keep Bears Wild and People Safe on Togwotee Pass Follow Ethical Wildlife Viewing and Photography Practices and Direction of Officials MORAN, WY — —In recent weeks, significant bear jams and...

The Mountain Bluebird: A Welcome Sign of Spring

There are few sights in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem more uplifting than the flash of brilliant blue wings cutting across a wide-open field. That’s the male Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides)—a vibrant burst of color against the earthy hues of Wyoming’s...

2025 Bear Season is Here – A Message from Bear Wise Jackson Hole

For Immediate Release March 26, 2025 The 2025 bear season is here We need your continued help to avoid human-bear conflicts JACKSON, WY — Bears across Teton County are becoming active with the spring transition. Adult male grizzly bears begin emerging from their...