A Bird in the Hand

While the saying has had many applications over the years (its first recorded use dates back to the 16th century!), “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” can be taken quite literally when it comes to bird banding. Having a bird in the hand allows researchers to take quantitative measurements and make up-close, detailed observations that, in most other contexts, would be difficult, if not impossible. What’s more, after multiple years of collecting such data, we can start to observe changes and trends within an avian population and, eventually, to make deductions about the health of the ecosystem.

This is largely the goal of the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program. Begun in 1989 by the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), the program is a cooperative effort to collect standardized data on North American landbirds. By increasing understanding of the factors that affect avian populations and their relationships, from a local to a continental scale, ecologists are able to make informed conservation and management decisions. Furthermore, the effectiveness of those decisions will be able to be measured once they have been put into action.

Beginning in June 2018, JHWF staff and volunteers will be leading banding efforts at two MAPS stations in the Jackson area. Both sites were started by the Teton Science School’s Teton Research Institute in 1991 and 2003 and were run by the Teton Raptor Center from 2014-2017. We hope to be able to contribute ongoing data for many years to come!

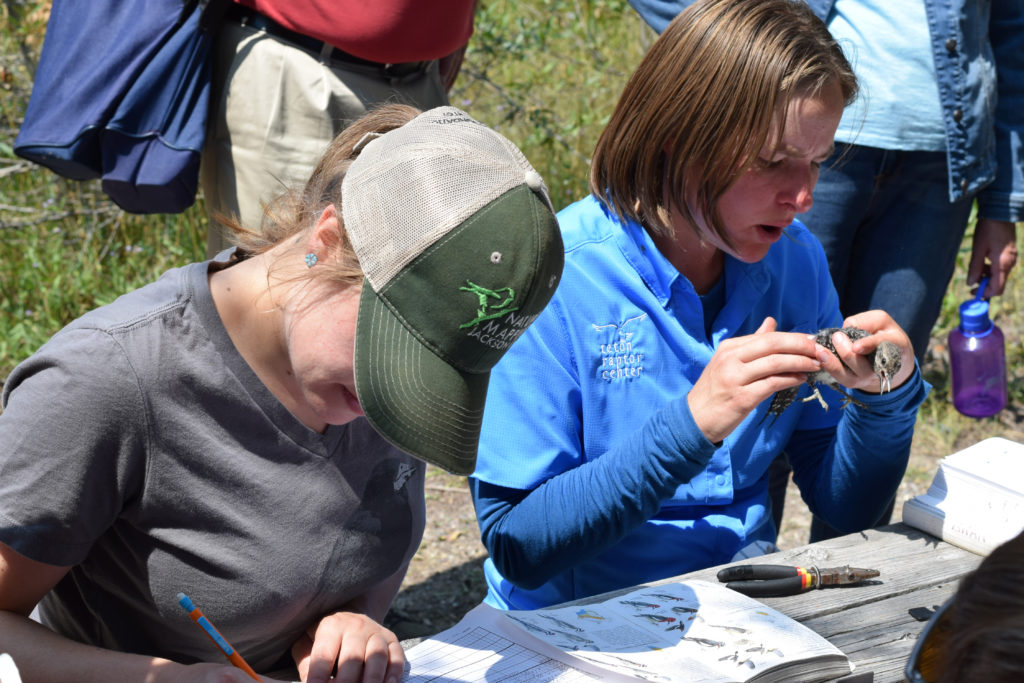

JHWF Associate Director Kate Gersh (left) records data provided by Teton Raptor Center’s Allison Swan (right) at a banding station in 2017. The two organizations worked closely during a transition year to ensure that the essential program would continue smoothly.

How does MAPS work?

MAPS stations use mist nets, placed at permanent locations within a designated study area, to safely capture birds. Banders extract the birds from the nests and bring them back to a centralized location, where they take various measurements and place a USGS-issued aluminum band on each bird’s leg prior to releasing it. Banding begins around sunrise and the nets are open for six hours during one day of every 10-day period. The season begins in May or early June, depending on latitude (that’s the first week of June for us, in Jackson Hole!) and runs through early August.

So what sort of data does one take from a bird in the hand?

After the species identification and band number (whether it is a newly banded bird or recaptured), the most important data we collect is the age and sex of the bird. Is it a young bird or an adult? Male or female? How exactly we deduce this depends on the species; however, many species of songbirds exhibit sexual dimorphism, meaning the males are visibly different from the females. During the breeding season, this is often most apparent in the bird’s plumage—males have on their “sexy plumage,” to help them attract a mate, while the females’ feathers are more subtle and subdued, to provide camouflage while they are on the nest.

A juvenile American Robin gets banded with a USGS-issued aluminum band with a unique number sequence. This will allow anyone who recaptures the bird in the future to identify it as the same bird!

Alternatively, by blowing on the bird’s abdomen to part the feathers, we can observe less obvious signs. In preparation for incubation, females will develop a bare patch on their breast and abdomen, called a brood patch, which allows efficient heat transfer to keep eggs and nestlings warm. In contrast, a male will develop a cloacal protuberance. A cloaca is the opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts of all vertebrate animals, regardless of sex, with the exception of most mammals. This orifice will swell as the breeding season approaches, allowing us to identify the bird as an adult male. In some cases, detail as subtle as wing or tail length is required to differentiate between males and females!

As with determining a bird’s sex, it is sometimes possible to figure out the age from the bird’s plumage, from the feather coloration and pattern and/or the shape and quality. The specifics depend on each individual species, but the basic idea is that a bird will have plumage distinctions as a juvenile (only recently having left the nest), a young bird still in its first year of life, and as an adult. Some species will retain certain feathers, usually in the wing feathers, that allow more detailed aging assessments to be made. The Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part 1, by Peter Pyle, is an invaluable tool that details information about individual species’ molt patterns and feather characteristics that assist in differentiating between ages and sexes.

As with any rule, there are, of course, exceptions. Generally, though, these are all pretty good indicators. That said, just as it’s good to use multiple clues when identifying a bird or any other animal in the field, so too is it good to use multiple measures when making age and sex determinations in the hand.

Plumage characteristics such as the red patch on the face, tail feather shape, and relative age of the wing feathers help identify this Northern Flicker as an adult male.

Additional measurements taken in the hand:

- Skull ossification – birds have hollow bones and their skulls are no exceptions. The skull develops in two layers, which are ultimately connected by small columns of bone, or “struts.” Upon leaving the nest, only the outer layer is completely formed and the inner layer progressively develops over the subsequent 3-12 months, leaving visible “windows” in the meantime. We are able to monitor this development and potentially use it or its completion to assist in aging the bird.

- Fat – birds’ fat stores are constantly fluctuating. While, during the breeding season, we wouldn’t expect a bird to be carrying much excess fat due to the constant flurry of activity, birds are able to increase their weight 75-100% by storing up fat in preparation for migration.

- Feather characteristics – is the bird actively molting? Is there wear to the flight feathers (wings and tail)? Does the bird have multiple generations of feathers?

- Wing chord – birds’ wings have a natural curvature to them that helps generate lift and allows them to be such effective fliers. We take this unflattened wing length measurement, which is a good indicator of the bird’s size, similar to height in humans.

- Body mass – we weigh the bird using a digital scale, recording the mass to the nearest 0.1 gram.

When able, we aim to take all of these measurements prior to releasing the bird. However, the safety of each and every bird is our priority and we are constantly checking in on the bird’s condition during the banding process. If the bird starts to exhibit signs of stress, we will let it go.

We are thankful for all the time and effort TSS and TRC have invested in continuing this long-term study and are excited to be able to contribute to this impressive data set. To learn more about the MAPS program and importance of long-term research, check out the MAPS project webpage. If you have any additional questions, please feel free to contact Kate Maley, the lead bird bander this season, at katelyn@jhwildlife.org or Kate Gersh at kate@jhwildlife.org. Happy birding!

A Cedar Waxwing perches nearby after being banded and released.

“