by jhwildlife | Nov 21, 2016 | Blog, Wildlife Friendlier Landscapes

From left to right: JHWF Board President Aly Courtemanch, JHWF Associate Director Kate Gersh, JHWF Executive Director Jon Mobeck, Wyoming Chapter of The Wildlife Society Board Member Ben Wise

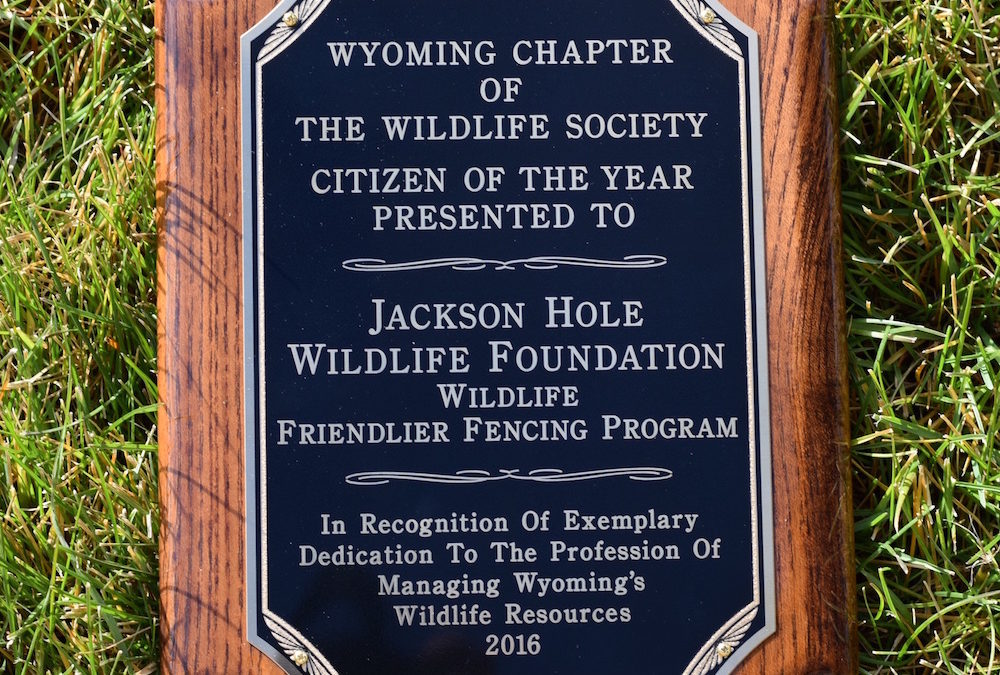

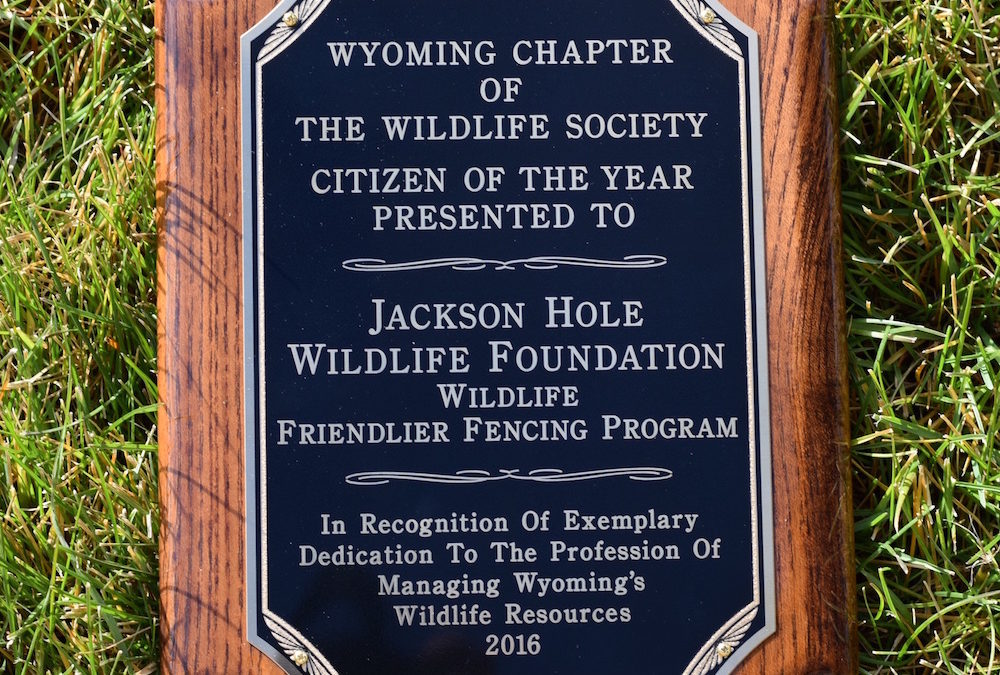

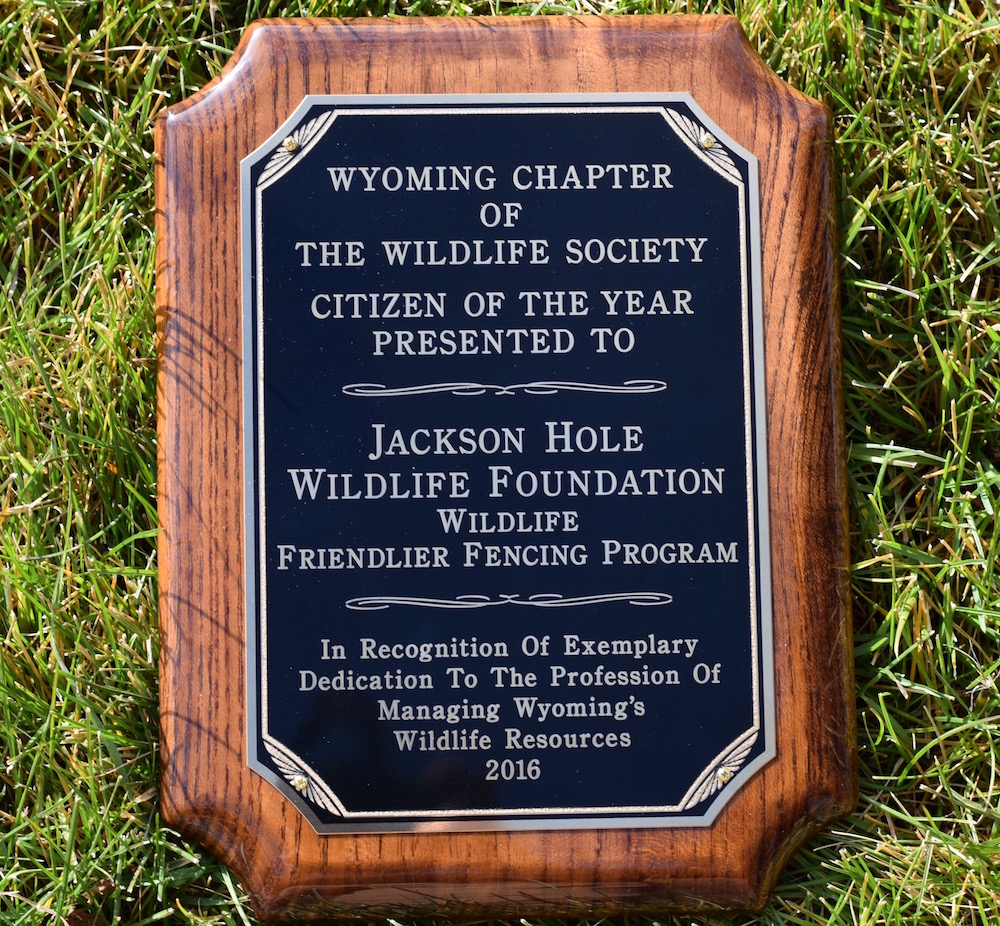

The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation received the Citizen of the Year Award for its Wildlife Friendlier Fencing Program on Thursday, November 17, at the Annual Meeting of the Wyoming Chapter of The Wildlife Society in Cody, Wyoming.

The Wyoming Chapter of The Wildlife Society Board Member Ben Wise announced the award at the closing evening banquet at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Wise introduced JHWF’s Executive Director Jon Mobeck to accept the award on behalf of the many hundreds of volunteers who, collectively, were recognized as Citizen of the Year. The Society typically gives the award to individuals who have made a significant contribution to wildlife management. Wise and other nominating agency partners from Wyoming Game & Fish and the Bridger-Teton National Forest saw an opportunity to celebrate the dedicated community that has formed around the Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program. The program’s impact exceeds the 183 miles of fence it has removed or modified over 20 years. It has also served to embody a community’s commitment to a land ethic that highly values landscape permeability.

In a brief acceptance comment, Mobeck alluded to Aldo Leopold’s oft-quoted mantra: “There are two things that interest me: the relation of people to each other, and the relation of people to land.” Mobeck concluded that one benefit of the Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program is that it advances meaningfully both of these relationships. JHWF believes that communities of people that come together for wildlife, especially throughout the rural West, may bridge social divides as we also clear barriers to wildlife movement. Since wildlife is a deeply shared interest in Wyoming – a Western passion – that connects people to each other, we believe that we can weave together the ethical fabric that allows a community to live compatibly with wildlife, while connecting individual communities to each other across a larger landscape. That ensures a bright future for wildlife in the Greater Yellowstone for generations to come.

JHWF Executive Director Jon Mobeck accepts the Wyoming Chapter of The Wildlife Society’s Citizen of the Year award on behalf of program volunteers at the closing evening’s banquet dinner.

The conference in Cody, which brought together 150+ researchers, students and land managers for three days of talks, workshops, films, field trips and social gatherings, reflected this spirit. By promoting collaborative science and land management – and refreshingly linking art and science by inviting the gifted artist James Prosek to deliver the keynote talk at the banquet – the conference aims to build healthy and resilient landscapes for Wyoming’s wildlife and people.

On the opening evening of the conference, JHWF’s film “Free to Roam” was screened to a receptive and engaged audience. “Free to Roam” captures the essence of the Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program and many of the individuals who have been involved since its origin.

JHWF’s Board President Aly Courtemanch and Associate Director Kate Gersh also attended the conference, which enabled the organization to make many valuable connections to extend its reach, and learn from some of the best wildlife managers and advocates in the state.

The Wildlife Friendlier Fencing Program endures because of the relentless volunteer commitment of many individuals as well as the financial support of individual donors and many foundations and agencies over the years. Thank you to all who have made a contribution to this effort!

Read a short piece about the Award in the Jackson Hole News and Guide.

by jhwildlife | Oct 26, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Eagle Scout is the highest achievement or rank attainable in the Boy Scouting program of the Boy Scouts of America. The requirements necessary to achieve this rank take years to fulfill, and must include completion of an extensive service project that the Scout plans, organizes, leads, and manages. Luckily for the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, prospective Eagle Scout Maclain Smith from Utah, made us the beneficiary of his service project. This past Friday afternoon, Maclain came up to Jackson to install 52 Mountain bluebird nestboxes that he and fellow Scouts constructed by hand.

With lots of laughs and great spirit, Maclain and nine of his family members spent a sunny autumn afternoon installing new pinewood nestboxes on half of our Mountain bluebird trail that runs along the western boundary of the National Elk Refuge. Our old nestboxes (that served their purpose for 13 years!) were taken to Teton Recycling Center where they will be repurposed into wood mulch and used for gardening and landscaping purposes. After 13 years, we felt it time to retire the old nestboxes as they had seen many repairs over the years, but their deteriorating condition was starting to present challenges in terms of predator control and protecting nests from bad weather conditions.

Not only are we fortunate to have the help of Maclain, but we currently have two more prospective Eagle Scouts producing a total of 72 additional nestboxes that will be installed this coming spring. Of these 72 — the other half of our trail will receive 52 new nestboxes, we are looking into placing additional nestboxes elsewhere on the National Elk Refuge, and keep a few in storage. Thank goodness for Scouts!

Click here to see a photo gallery documenting Maclain installing new Mountain bluebird nestboxes with the help of his family and JHWF staff.

Click here to read an account of the project published by the National Elk Refuge.

by jhwildlife | Oct 17, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

Registration is now open for the first ever Wyoming Citizen Science Conference! Hosted by the UW Biodiversity Institute, the conference will involve keynote and breakout sessions that guide program managers and citizen science participants (teachers, Scout leaders, community activists, etc.) to weigh in on what works well (and what doesn’t) in terms of having a successful, impactful citizen science program. The conference will be held in Lander, Wyoming, on December 1-2, 2016, and with an optional day on Saturday, December 3 to attend focused workshops.

We hope you can join us. The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation will be in attendance to represent Nature Mapping Jackson Hole – delivering two oral presentations and presenting two project posters in addition to, screening the film Far Afield. We’ll mainly be talking about lessons learned from the past eight years of Nature Mapping Jackson Hole, sharing our experiences and intending to learn much from others in attendance that will come from across the state. The organizers of this inaugural event hope to have a strong representation from active citizen scientists, not just those serving in professional capacities. Register today and come learn, share and be inspired!

Details on the conference agenda can be found here.

by jhwildlife | Oct 11, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

By Frances Clark, Nature Mapper and Botanist

Hiking under Engelmann spruce trees has been hazardous this fall. Light brown cones, 4-6 inches long and sticky with pitch, pour down amidst harsh chattering from above. I have counted one cone falling every 3-5 seconds, another time I couldn’t keep track of the barrage. Cones landed on my head, bounced and then lay strewn about my feet. Cone storms. What s going on?

Red squirrels are taking advantage of a “mast year.” Last spring, you may remember, prodigious amounts of pollen wafted on the wind. Some of that pollen landed on tiny female cones, which have matured, securing two winged seeds under each scale. Spruce trees are now laden with dangling cones from the top down. This abundance occurs every 2-3 years in spruce. The intervening times are lean.

Red squirrels are taking advantage of a “mast year.” Last spring, you may remember, prodigious amounts of pollen wafted on the wind. Some of that pollen landed on tiny female cones, which have matured, securing two winged seeds under each scale. Spruce trees are now laden with dangling cones from the top down. This abundance occurs every 2-3 years in spruce. The intervening times are lean.

Well adapted to feast and famine, red squirrels form large middens—stores of thousands of cones. They efficiently sample and then harvest trees with the most seed energy per cone and with the greatest cone abundance. Middens lie at the center of the most productive group of trees.

A midden can best be described as several inches of cone scales and cores heaped over mineral soil, forming mounds up to several feet high and wide. The loose surface often has shallow holes in it. In the mineral soil below, there may be a network of tunnels. Squirrels pack several cones, pointed end down, into holes which will be covered eventually by more scales and cores. In this cool and moist environment—a humidor—cones will remain unopened for at least 1-2 seasons until the squirrels retrieve them. When they do, squirrels eat cones like corn-on-the-cob, scattering scales everywhere while consuming the nutritious seeds. It has been calculated that squirrels consume 50-156 cones a day and stash 10s of 1000s in a midden in a good year. No wonder red squirrels are so territorial – chattering loudly at any perceived threat and dashing out to their territorial boundary: they are defending their stash for winter survival.

While cones are preferred, in lean times and in summer, red squirrels will eat other items. Fungi are particularly relished, with parts hung up in trees to dry. They eat buds, fruits, sap, even cambium and phloem, as well as eggs and insects. Small plant parts placed in middens may help train young squirrels for future hoarding. In different years, squirrels may harvest cones of Douglas firs – which have mast years every 4-5 years, or as back up, serotinous cones of lodgepole pine. Lodgepole pine cones are often gathered on top of middens. They do not open even when dry, are too tough for other predators to eat, and seeds remain viable for years. The squirrels don’t need to spend extra energy to bury them.

The other day, walking around Moose Ponds, I heard several red squirrels churring within a stand of battered old spruce and fir trees. Their density indicated good habitat. Tangles of downed limbs and saplings surrounded straight, scaly boles clad in densely needled branches, which intertwined to form a closed, irregular canopy. Engelmann Spruce reach peak production at 150-200 years and provide diverse cover, escape routes, and nesting sites. Old growth trees are excellent for red squirrels.

As red squirrels are active all winter, nesting sites are vital for thermal regulation. Tree squirrels prefer natural cavities, but these are often in short supply so instead squirrels will build a nest of leaves and grass 12 to 60 feet off the ground. Other options include “witches brooms,” an aberrant growth pattern where twigs are unusually dense. They will also burrow into tunnels under their middens for warmth and safety.

Nest sites are located within 100 feet of larders so squirrels can readily defend and retrieve their stores. Circular territories may be 1-2 acres centered around a midden. I nature mapped six squirrels – six territories – on my route past Moose Ponds. While dutiful, I wish now I had taken more time in this rough old patch of forest to see where the middens and nests might be.

Predators come from air or ground. Squirrels may have different calls depending on whether or not a threat is aerial or terrestrial. One study indicates that red squirrels produce a high frequency, short “seet” sound similar to alarm calls of birds. This sound is hard for raptors, such as Goshawk, Great Horned Owl, or Red-tail Hawk , to locate or even hear. A louder bark call is used for overland threats, such as a Pacific (pine) marten (12-20% of marten diet is red squirrels), weasels, or fox. Once alerted, squirrels scramble and hide in dense vegetation.

Between predation and starvation, only 25% of squirrels survive into their second year. Females are in estrus for one day only in early spring. Many males, one dominant in the lead, will give chase and several may succeed in copulation on that one day. In just over a month, the female gives birth to an average of four young which will be independent in another 70 days, by early fall. While mothers may share a territory with daughters, they kick out sons who must then find and defend their own territories by winter. Often the most successful males have ventured the farthest to find a relatively large territory containing an abandoned midden. Midden sites are often used by many generations. In autumn, youngsters and seasoned squirrels are particularly territorial, defending boundaries while gathering cones, which is why they are so vociferous.

Red Squirrels are the most frequently Nature Mapped small mammal with 305 observations over the last seven years. Even so, many of us pass them by – unrecorded – on our hikes. In your next excursions through a conifer forest, listen for chatter. Can you hear differences in their calls? Can you discover a midden nearby? Does a squirrel bound toward you to defend its territory or scurry up a tree or down into a tunnel to escape? Can you find its nest? All these behaviors are fascinating to watch while you may, or may not, log a new Nature Mapping observation.

References:

Animal Diversity Web ADW: Museum of Zoology University of Michigan. Tamiasciurus hudsonicus Red Squirrel. Accessed 10.8.16: http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Tamiasciurus_hudsonicus/

Finley RB. Cone caches and middens of Tamiasciurus in the Rocky Mountain region. Misc. Publ. University of Kansas Museum Natural History. 1969;51: 233–273. https://archive.org/stream/cbarchive_36740_conecachesandmiddensoftamiasci1969/conecachesandmiddensoftamiasci1969 – page/n17/mode/2up

Greene E. Meagher T. 1998. “Red squirrels, Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, produce predator-class specific alarm calls.” Animal Behavior. 1998 Mar; 55(3): 511-8. Accessed through: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9514668

Steele, M.A. 1998. “Tamiasciurus hudsonicus” Mammalian Species 586, pp. 1-9. : published by the American Society of Mammalogists. http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-586-01-0001.pdf

Streubel, D. P. 1968. “Food storage and related behavior in red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) in Interior Alaska.” Masters Thesis. University of Alaska. Source: http://www.arlis.org/docs/vol2/hydropower/APA_DOC_no._3351.pdf

U.S. Forest Service data base: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/animals/mammal/tahu/all.html

by jhwildlife | Sep 1, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF) is proud to support the 2016 Wyoming Citizen Science Conference! JHWF’s Associate Director, Kate Gersh, serves on its program planning committee. We are also supporting the conference as a silver-level sponsor. Taking place this coming December in Lander, the Wyoming Citizen Science Conference (hosted by the UW Biodiversity Institute) is the first of its kind in our state, and will focus on the problems and solutions that citizen science program managers and volunteers face when implementing and participating in programs. Wyoming in particular faces interesting and specific challenges when designing, delivering, maintaining and evaluating citizen science programs. How does the state’s rural population influence recruitment and retention? How does the remoteness of some study areas and the high diversity of plant and wildlife impact study design? How can we make citizen science accessible and useful to teachers? What laws and rules do we need to be aware of?

We anticipate approximately 200 attendees, including program organizers, educators and citizen science volunteers. JHWF staff and many of Nature Mapping Jackson Hole’s Scientific Advisory Committee members plan to attend and present. JHWF also encourages our community’s citizen scientists to directly participate in the conference by delivering presentations or workshops of your own accord. Download the call for proposals here.

Proposals are due Sunday, September 18, 11:59 pm MST. Submit the completed form in Word or PDF format to UW Biodiversity Institute Project Coordinator Brenna Marsicek at brenna.marsicek@uwyo.edu.

Also, please save the conference dates of December 1-3, 2016, in your calendars. We very much hope to see you at this unique event that will for the first time link our statewide efforts.

by jhwildlife | Aug 8, 2016 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

For thirteen years, volunteers have been maintaining a bluebird trail along the boundary of the National Elk Refuge. It is the largest Mountain Bluebird trail in the United States, and it provides essential nesting habitat for these iconic birds, as well as long-term scientific data. This citizen science project is core to the mission of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation: Combining science and the celebration of wildlife.

About Mountain Bluebirds

A male Mountain Bluebird. Photo: Chuck Schneebeck

The brilliant-blue males arrive in Jackson Hole starting in March and begin to select and defend boxes. The pale blue-gray females arrive shortly thereafter and choose a mate based solely on the quality of the nest cavity. They build the nest to fit several eggs—similar in color to Robins’ eggs, but smaller. The males feed the incubating female, often hovering and diving to catch insects such as beetles and grasshoppers.

Phyllis Greene, long-time monitor and past project coordinator, has observed: “They lay one egg a day, but the eggs hatch out all at once. It’s fun to watch. I have seen the chicks peck out through the shell. When they hatch, they are the size of your pinky and nude. First thing, they have their mouths open for food. They are adorable.” The chicks develop pin feathers and then “become more of a bird.” The monitors observe the nestlings from afar after the first 12-14 days so that the birds won’t fledge prematurely. Then after about 3 weeks total, ”They fly off. ‘Ok, good-bye.’ It’s sad. They are so gorgeous.” Adult males depart Jackson in early August. The females and young leave a little later. These birds, considerably smaller than a robin, migrate as far south as Mexico and Central America.

Nesting success is tenuous. While Tree Swallows arrive two weeks later than Mountain Bluebirds – after many bluebirds have claimed boxes – they often out-compete the bluebirds when they would otherwise attempt a second brood. Tree Swallows are a beautiful, native bird, so their presence is enjoyed as well, despite the challenge to bluebirds. Future nestbox plans aim to accommodate the greatest number of both species. Also, according to project coordinator Tim Griffith, weasels and raccoons have been known to raid the nests, which lowers the success rate. Overall, the North American Breeding Bird Survey indicates Mountain Bluebird populations declined by about 26% between 1966 and 2014. We will continue to analyze our data to see how the birds have been faring here in Jackson Hole.

The Origin of the Mountain Bluebird Nestbox Trail Project

Female Mountain Bluebird. Photo: Chuck Schneebeck

Chuck Schneebeck started the project in 2003. He read a study about the loss of aspens due to intensive ungulate grazing on the National Elk Refuge (NER). Bluebirds are cavity nesters, naturally using holes in old aspen trees carved out by woodpeckers or formed by a rotted tree limb. On the Refuge, the loss of standing aspens due to elk browsing meant the loss of nesting habitat. In an informal survey, “We found only one nest from Flat Creek to the Gros Ventre River, in an electrical box by the visitor center.” Chuck realized that to mitigate the impact of grazing, “We could build cavities: nest boxes.” Having worked on a bluebird trail for the National Audubon Society in Dubois, WY, he knew how to start.

From the beginning, Chuck engaged the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and community. The Foundation provided funds for the materials and Chuck donated his labor. With the cooperation of NER, he and others set up 105 boxes 100 yards apart placed five or more feet high along the western boundary fence. Citizen science volunteers were assigned about 15 boxes each, which requires a mile walk and about an hour a week to monitor. They start surveying in April and continue into August. Monitors also help clean out and repair the boxes in the off-season.

The Monitoring Process

Kate Gersh, JHWF Associate Director and project monitor

Phyllis Greene’s approach is, “We talk to the box and tap first, saying ‘Hi, coming to see you. How you are doing?’ Then we open the lid and look in. Mom just looks up and blinks her yes and says ‘how do you do?’ We close the lid then record what we saw. They don’t mind the monitoring and we never touch them.“

Phyllis goes on to say that the monitors become “very maternal or paternal. We want to give the birds a chance because they are almost extinct out here.”

While monitors are surveying along the road, people often stop and ask what they are doing. “We explain the project and they respond, ‘That’s great!’ People get excited and appreciate that someone is doing something for these little birds,” recalls Phyllis.

How do volunteers feel about the project?

For Chuck Schneebeck – project founder – while the project does not supply all the complexity that the bluebirds need, “We are doing what we can. The fundamental part is that we have cavities and bluebirds have been using them for a long period of time. So there are lots of birds now.”

Phyllis Greene, who took over the project from Chuck: “The important thing is for the birds to have an opportunity to have a nest, to get out of the weather and survive. We want to make sure they have a chance. Originally they were almost extinct in lots of places throughout the US, not only here. Anytime we can help wildlife sustain itself and still be independent is a great idea.”

Jon Mobeck, Executive Director of JHWF says the project fits the mission of the organization. “This is a visible way to demonstrate how to mitigate our impacts of development on wildlife. It is a perfect example of the community coming together and helping out this beautiful species. It combines science and the celebration of wildlife.” And more personally, Jon had no experience with birds prior to taking on 12 boxes with the JHWF staff. He is becoming a bird watcher. “Now I have a whole new way of observing the environment. It has been eye opening and ear opening. A tremendous gift.”

Tim Griffith, our new project coordinator, has been engaged with Eastern Bluebird trails for years in Indiana before moving here a year ago: “This is the largest registered Mountain Bluebird Trail in the continental U.S. Mountain Bluebirds are crashing throughout the region. With 13 years of data, we can know more about the population and be responsive to changes in trends upward instead of downward. The more we know about this iconic western species the more we can save and increase their populations here and elsewhere.”

Natalie Fath, Volunteer Coordinator and Visitor Services Manager for the National Elk Refuge: “The ongoing collaboration with the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation on the Mountain Bluebird Nestbox Trail Project is essential to ensuring that monitoring, box maintenance, and reporting occurs. The NER is not only supportive of the collaboration, but also depends entirely on volunteer citizen scientists to give this project life due to Refuge full-time staffing limitations. Without volunteers, this project would not exist.”

Future Plans

A male bluebird watches as a monitor approaches. Nestlings are getting ready to fledge.

Next year, Tim plans to start banding birds to see how many return, and to which boxes. Eagle Scouts are ready to repair and build more boxes to place at other areas in the Refuge. Also, we will digitize the years of data for submission into our Nature Mapping database and Cornell’s national NestWatch system.

Jon Mobeck sums it up, “The Nature Mapping Bluebird Nestbox Project is a great way to introduce citizen science to the community. It is a visible and fun project. We welcome new volunteers!”

We thank the ongoing core project volunteers who are still in the valley:

Chuck Schneebeck, Ed Henze, Bert Raynes, Paul Anthony, Phyllis and Joe Greene, Loretta Scott, Larry Kummer, Julianne O’Donoghue, Gretchen Plender, Shelly Sundgren and Dave Lucas; Jon Mobeck, Kate Gersh, Christine Mychajliw, Tim Griffith.

Additional thanks to Jackson Lumber, which often donates cedar wood for the boxes.

Contact Tim Griffith to help out: Timgrif396@gmail.com.

References: