by jhwildlife | Aug 14, 2018 | Blog

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

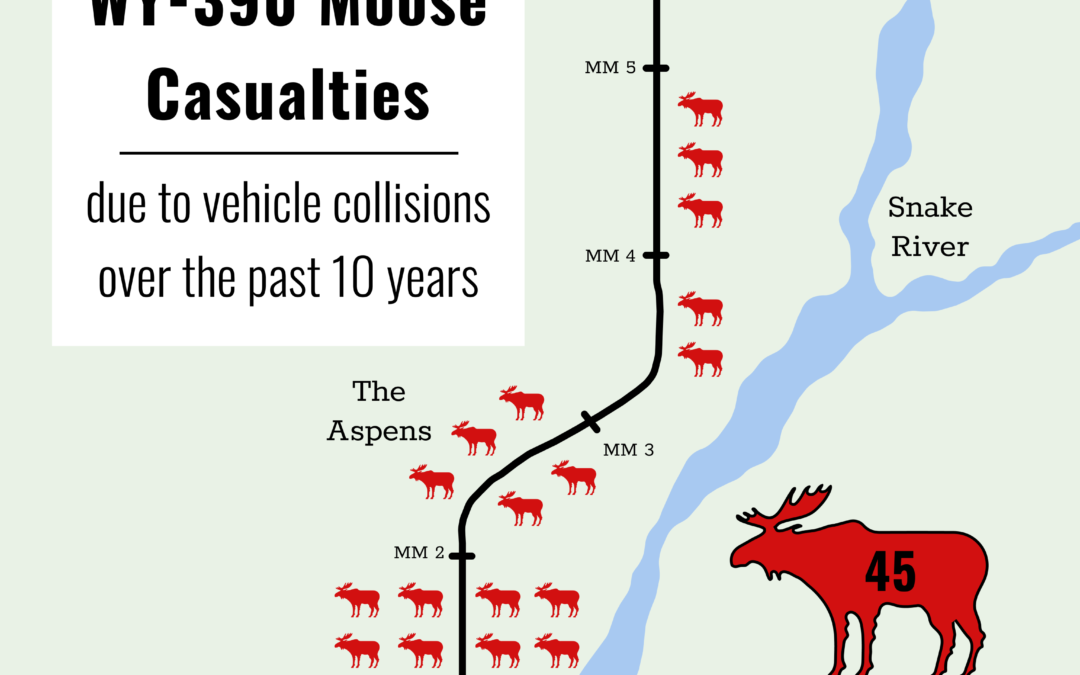

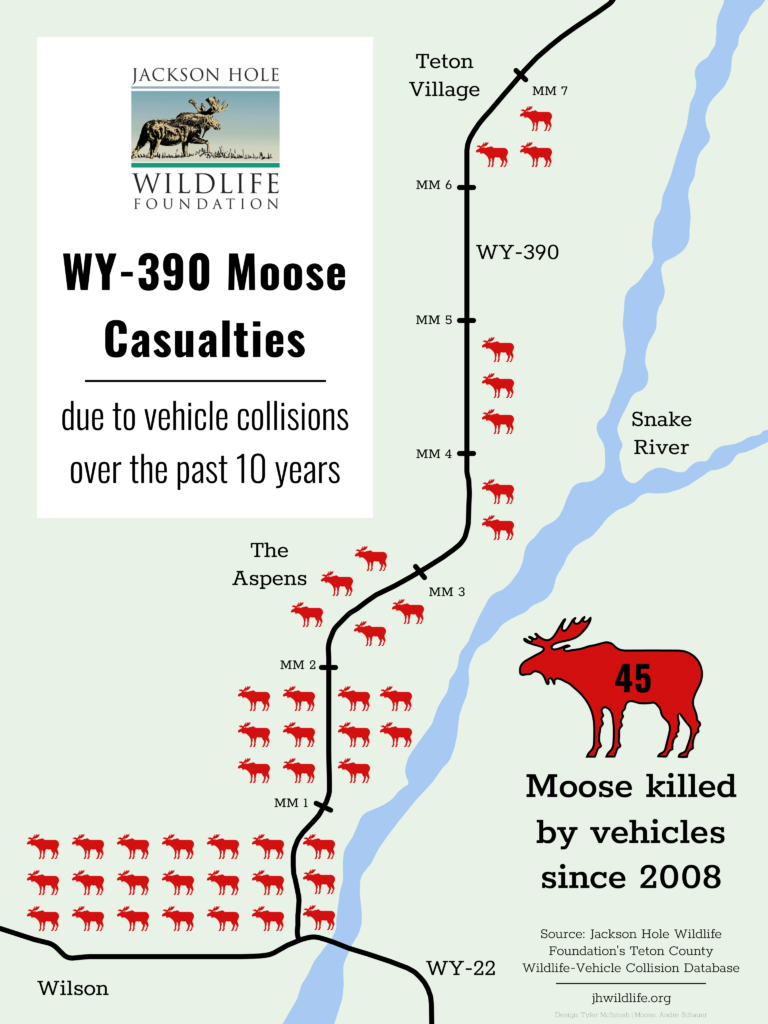

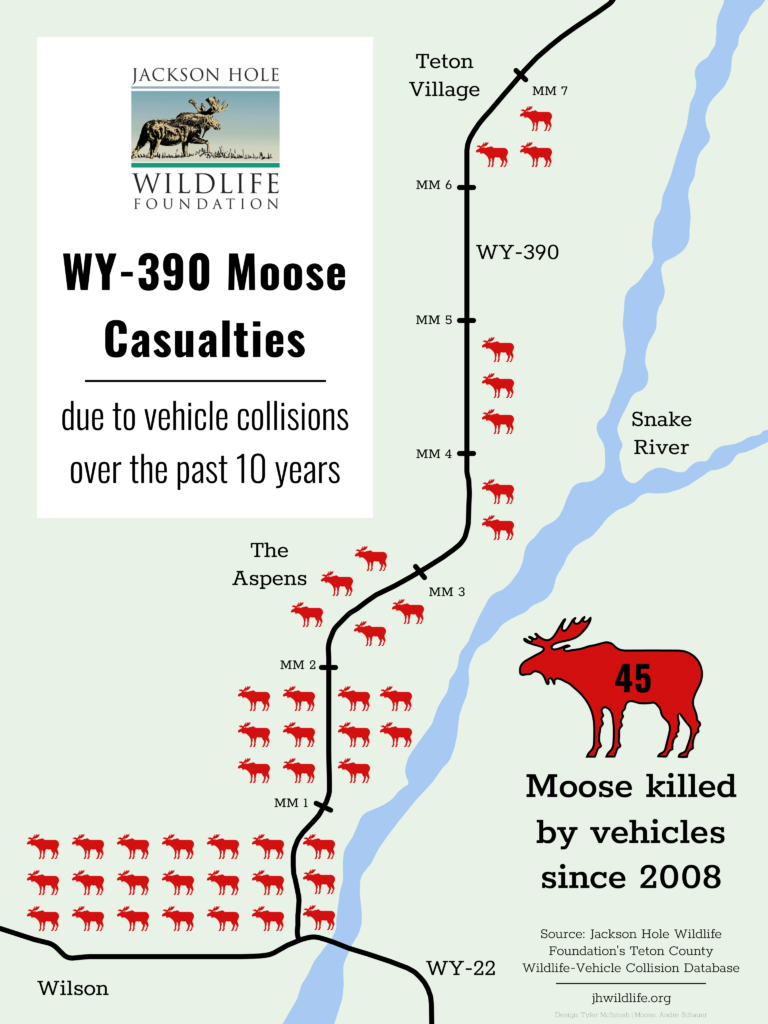

Three moose were hit and killed by vehicles on WY 390 in July, the last of which was killed during daylight hours, which is very rare – about 90% of moose collisions with vehicles occur at night. Summer collisions with moose are also relatively uncommon. The last time a moose was killed on WY 390 in the month of July was 2009. Of 45 moose casualties recorded since 2008 on that highway, only 13 (29%) have been hit during summer months (May-October), and just five along the one-mile stretch of highway adjacent to the Aspens development. While we receive many calls and emails when a moose is killed by a vehicle, we want to ensure that we refer to our collected data to consider potential responses and initiate any near-term, site-specific actions. We also consider how short-term actions fit within larger county-wide objectives. All in all, we want to make sure that our response is thoughtful and makes sense based on the many variables at any given site. While doing so, we don’t want to diminish the value of the animal that succumbed to a human-caused death. For the animal struck, statistics don’t matter. For prioritizing our actions, though, statistics are essential.

The recent “flurry” of moose casualties sounded alarms in Moose-Wilson neighborhoods and throughout the valley. While the reality is that one animal is hit on a highway each day in Jackson Hole on average, each individual moose collision – particularly within this corridor where backyard moose are beloved – is a newsworthy event, as it should be. The challenge of such newsworthy events is to make sure that they are viewed in context, while also recognizing the tragedy of the loss of another iconic animal. In short, what do we do about it?

The data reflects the fact that the largest problem on WY 390 occurs within the first few miles. Since 2008, 82% of all collisions on WY 390 have occurred in the first 3 miles, with nearly half of all collisions occurring in the first mile. If you add WY 22 to the mix (1/2 mile to the east and west of the WY 390 intersection), six moose have been killed within 1/2 mile of the junction to the east, and three moose have been killed within 1/2 mile to the west. All told, 30 moose have been killed in the past decade within one mile north of the WY 390 / WY 22 intersection and one mile to either side of that junction.

In terms of trends on WY 390, only five moose were killed between 2015 and 2017 (three of the five were hit in the first mile) so we have had a relative respite from the 26 that were killed from 2011-2013. Many campaigns launched simultaneously by citizens and organizations may have helped to reduce collisions along the length of WY 390. The combination of those measures (nighttime speed limits, fixed radar feedback signs, digital message signs, public awareness campaigns) is helpful, even if the small sample size makes drawing direct correlation between any one of those measures and the reduction in collisions inconclusive. The trend along most of WY390 is positive, but the intersection area remains the largest concern. We are also keenly aware of the possibilities and limitations with respect to potential structural measures through that densely inhabited corridor. We need to do what we can, where we can, as soon as we can.

In consultation with WYDOT, recently we decided to change the language on digital message signs to reflect the number of animals hit in July, stressing the severity of the issue to drivers. Many other near-term actions have been discussed, ranging from modifications to the existing reduced speed limit zones to improving sight-lines via vegetation removal to enhanced education campaigns with rental car companies and Teton Village hotels. It is never a bad thing to make people aware of the impacts that driving can have on wildlife, from ungulates to raptors. These collaborative efforts will continue between agencies and partners, spanning the entire Teton County highway network.

Teton County has also just released its Wildlife Crossings Master Plan, and accompanying Action Summary. Unsurprisingly, the WY 22/WY 390 intersection ranks as the highest priority for action. As with all locations, agency and organizational partners discuss immediate opportunities to change things for the benefit of wildlife and human safety. We don’t wait around for a long-term fix if any helpful measure can be initiated today. Some of those near-term options are still being considered for the intersection area. However, given the severity of the issue there and the possibility of much more frequent roadway occupancy by moose (given the proximity of ponds and willows on all sides), the ideal scenario is to separate animals from the highway via wildlife underpasses. The terrain lends itself well to that solution since the road is elevated and the areas of interest to moose are well below the road grade. While fencing long stretches in any direction in that area will be challenging (longer fencing typically increases effectiveness), modest fencing in the immediate area of the intersection should not impair views and serve the purpose of “funneling” animals to the underpasses (probably the best solution). The exact outcome (solution) has not been arrived at given the complexity of the area and many potential options, but it is important for the public to recognize that those discussions are ongoing. The public itself will have an opportunity to weigh in, as WYDOT seeks input on its planned work on the Snake River Bridge and WY 22/WY 390 intersection, slated for 2023.

If you would like to learn more about potential wildlife crossings plans there and across the county, you can access the Action Plan (recommendations of advisory committee) and the full Master Plan at the county website here. Page 7 of the action plan identifies the WY 390/ WY 22 intersection as the highest priority site, and it briefly discusses potential solutions. https://www.tetoncountywy.gov/1639/Wildlife-Crossings

The Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and Greater Yellowstone Coalition are tremendous resources for wildlife crossings work. You can visit with them about this issue, as well as the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, at the Alliance’s Summer Block Party at the Center for the Arts on August 29 from 5:30 pm – 9 pm. Come out and tell us what you think! In the end, we just want to ensure that we’re doing the right thing, in the right place, for the safety of people and for the good of wildlife.

by jhwildlife | Aug 13, 2018 | Blog, Wildlife Friendlier Landscapes

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

Saturday, August 11 was the sort of sunny scorcher that forces even the most ebullient dogs to slink into the shade. These are the days that force siesta. Yet despite the 95-degree heat, 35 dedicated souls showed up to the Hardeman Meadows north of WY 22 to help Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and the Jackson Hole Land Trust improve fences for safer wildlife passage. Some of Saturday’s volunteers have been on most of our projects this year, which is remarkable itself, but especially gratifying when any of them could have chosen to sit this one out and stay cool. That’s just not the way these wildlife-nuts operate, though. They’ll be there. They’ll get it done. Amazing.

Eleven middle school students also joined us, arriving with three instructors from Teton Science Schools, to dislodge (demolish!) top rails on a fence that will be replaced. It wasn’t hard to inspire the kids to whack away with their mini-sledgehammers! They did great work and lifted us up in the hot afternoon with sunny dispositions. Thanks, boys!

By 2 pm, we had removed more than 3/4 of a mile of fence, and hammered staples into posts on a fence now lined with smooth wire that can be dropped to a single strand when the pasture is not in use – a standard Wildlife Friendlier Fencing modification. Importantly, all of the volunteers stayed well hydrated – few moments passed without someone shouting “are you drinking water?!” – and completed the project safely.

JHWF is grateful to its volunteer fence team leaders – Randy Reedy, Scott Landale, Steve Morriss, and Gretchen Plender – and to Teton Science Schools as well as the Jackson Hole Land Trust (especially Erica Hansen and Steffan Freeman) for another rewarding day making the landscape just a bit better for wildlife! We’ve now removed or improved 5.5 miles of fence this summer.

We’ll get after it again on August 25. Join the herd!

– Jon

by jhwildlife | Jul 27, 2018 | Blog

Wildflowers abound this time of year, throughout the valley and up amongst the high peaks of the Tetons and Gros Ventres. Alpine prairies provide vivid photo-ops as we hike past vast fields of green, yellow, purple and red. As humans we tend to naturally appreciate these broad vistas but forget that this palette of natural color only exists thanks to a minuscule, but miraculous phenomenon between plants and their animal neighbors. Most of us have heard of pollination, but many of us probably have not looked into what a truly complex and rather strange process it is.

Pollination is a symbiosis, a relationship between living organisms, but more specifically it is mutualism – a symbiosis where both species in the relationship benefit. When insects, birds and even bats land on a flower and drink the nectar provided by the flower, parts of their bodies come in contact with that plant’s pollen, which are essentially the plant’s male reproductive cells. When the pollinator travels to its next nectar source, that animal shakes off some pollen from the previous flower and helps fertilize the female reproductive cells in the new flower. Essentially, the pollinator gets a reliable source of food, the plant gets fertilized, or rather “pollinated.” Seems like an odd way to reproduce, right? Scientists believe that this strange relationship between animals and plants evolved very early in the history of flowering plants, or “angiosperms.” It is also believed that the evolution of pollination quickly enabled flowering plants to reproduce super effectively, thus allowing for rapid diversification of this particular group of plants; partially explaining why angiosperms are today, one of the most diverse groups of living organisms with about 300,000 known species.

-

-

Broad-tailed Hummingbird

-

-

Field Crescent Butterfly

-

-

Bumblebee

Humans still have much to learn about pollinators. Just within the last few decades have we understood the importance these animals have to our existence – studies have shown that 1 out of every 3 bites of food people eat is created by pollinators. Yet many bee and butterfly populations and ranges are still unknown even throughout the United States, although we now know that several are struggling. Bees have been in many headlines lately – “Save the Bees” has become a common tagline. However, with the focus being on non-native honeybees that are not actually threatened with extinction, native bee species that are more efficient and more widespread pollinators are often left out of the spotlight. Many of these species (including a few found in Teton County) suffered estimated population declines of 80-95% due to habitat decline and possible pesticide poisoning.

Anise swallowtail

Today, 33 species of butterflies and moths are listed as federally endangered, and only in the last 3 years have native bees been recognized and listed as being threatened with extinction. All species of pollinators protected by the federal Endangered Species Act can be found here.

There are various field guides and online resources for identifying birds and butterflies throughout Wyoming, but far fewer for less conspicuous insects like bees and beetles. Linked below is a field guide to western bumblebees produced by the U.S. Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership and modified for Wyoming, by the Wyoming Biodiversity Institute, as well as a great article by researchers at the University of Wyoming explaining various types of bees in detail. Most bee species can be difficult to tell apart (even under a microscope), but bumblebees require less of a learning-curve because their identification usually relies on color patterns on different body parts, just like butterflies and birds! Why not extend your wildlife searches to a smaller scale, and challenge yourself to identify pollinators like butterflies and bumblebees?

Additional Resources:

https://wyobio.org/files/2614/1174/2125/printablebeeguide.pdf

http://www.uwyo.edu/barnbackyard/_files/documents/magazine/2016/summer/wynativebees0716.pdf

https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/features/posters/WesternBumblebeesPoster_print.pdf

by jhwildlife | Jun 22, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

by Max Frankenberry, Assistant Bird Bander

Jackson Hole has officially entered the season of sun and snowmelt. Tourists are making their way through town to and from the parks, and the bustle around downtown Jackson has gotten exponentially louder. But step outside of downtown to the National Elk Refuge, a Cache Creek trailhead or even your own backyard, and you notice that human sounds aren’t the only noises that get louder this time of year. Choruses of birds at dawn, trills of surprised ground squirrels in the afternoons and the croaks of frogs in the evening remind us that this is quite the time to be alive in the mountains.

Boreal chorus frog – Gibbon Meadows; Credit: Neal Herbert; May 2014

These symphonies are enjoyable and relaxing to say the least, but they can also be valuable identification tools for Nature Mappers! Learning to ID bird songs, frog calls and even mammal sounds opens your range of observation drastically. Boreal Chorus frogs may be experts at wetland camouflage, and can even avoid our eyes when we’re right on top of them, but learn to recognize their calls and those hidden creatures become as obvious as a moose in the sagebrush. And what better time to start than the summertime! Many species are the most vocal during this time of year, and a walk down your street in the early morning or in the evening can be a great place to begin soaking in those summer sounds.

Wildlife Identification by Ear Resources

Attached below are some excellent resources for learning amphibian and bird songs in particular. Our Nature Mapping database has been especially lacking in amphibian observations, and we know they are out there! Identifying wildlife by ear is a valuable skill, and practice makes perfect. The more practice you put in, the more species you can confidently Nature Map this summer!

Calls of Wyoming’s Frogs and Toads – https://www.wyomingbiodiversity.org/index.php/Initiatives-Programs/CitSci/rocky-mountain-amphibian-project/wyomings-amphibians/amphibian-calls

Bird ID Skills: How to Learn Bird Songs and Calls – https://www.allaboutbirds.org/how-to-learn-bird-songs-and-calls/

Mammals Sound Gallery – http://www.bioacoustica.org/gallery/mammals_eng.html

by jhwildlife | Jun 18, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

by Frances Clark, Lead Ambassador Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

At this time of year, people see their lawn and gardens riddled with ground squirrels or pocket gophers or their trees chewed to toppling by beaver and ask, “What is the purpose of these pests?”

Small mammals serve as prey for our large mammals and raptors and provide other ecological services, such as aeration and recycling of soil and nutrients. Beaver, our largest rodents, form habitat for many other creatures, although they are a nuisance to homeowners with ponds and aspen plantings.

Small mammals serve as prey for raptors and other animals. Photo: Steve Jurvetson

Uinta ground squirrels are common in sage and grassland habitats, and they find similar features in lawns. They dig tunnels and form sleeping chambers, thereby creating holes and mounds, much to the consternation of homeowners and ranchers. I have nature mapped dozens and dozens of ground squirrels driving out the National Elk Refuge road in spring. Indeed they emerge and mate in April and each pair can produce four to seven young by May, which then scamper about every which-way eating grasses and flowers. Their abundance can seem overwhelming, even repulsive.

Driving out this same route a day in mid-June, I spied several red-tailed hawks, Swainson’s hawks and even golden eagles soaring overhead and a coyote or two trotting through the fields, ears alert. The high-pitched alarm calls of ground squirrels came from all directions. I realized the abundance of raptors was due to the plentitude of squirrels. Uinta ground squirrels are tasty packets of protein. They are a necessary and timely food source for raising young raptor chicks, red fox kits and coyote pups. And the time is short… Uinta ground squirrels are above ground only three months before they go dormant in August for the next nine months. Many don’t make it.

Other raptors, including northern harriers, prairie falcons and American kestrels, hunt open areas for rodents in sizes appropriate to their body weight. In addition to Uinta ground squirrels, least chipmunks, meadow voles and deer mice are important components of their diets. In old growth forests, red-backed voles nourish northern goshawks and pine martens. Great horned owls also devour small mammals. Fortunately, most small rodents don’t bother us humans.

Another annoyance in cultivated areas is northern pocket gopher. As snow melts, one can see the extensive “eskers” that mark the pocket gophers’ progress underground eating roots, rhizomes and tubers for food. In summer, occasional fresh mounds of soil indicate areas of activity. Rarely does one see a whiskered grey face, with tiny eyes and ears, emerge from a hole. Bear, fox and coyote use their ears to find this plump fossorial (digging) prey. The Teton Raptor Center is monitoring pocket gophers as part of their population studies of the majestic great gray owl. Great gray owls can hear pocket gophers moving under feet of snow and plunge feet first to catch their vital winter meal.

In addition, pocket gophers are particularly important in enhancing soils in mountain meadows. Their prodigious earth movement churns up nutrients, allows water and air to seep into hard-packed soils and provides opportunities for seed germination.

Young beaver move up creeks and irrigation ditches to find new territory to raise a family. The sound of running water and presence of willows and aspen stimulates dam building. Some of these appealing sites are now landscaped into ponds surrounded by aspen trees. Beaver build dams to impound water to serve as moats and insulation for their lodges, where they raise their young and keep safe. Anyone who has visited Schwabacher’s Landing or Moose-Wilson Road in the park has witnessed the diversity sustained by these industrious rodents. Beaver impoundments encourage willows, sedges and aquatics, which in turn provide food and shelter for ducks, sora, amphibians and moose. The U.S. Forest Service and other groups are moving trapped beavers up drainages to enhance wildlife habitat and also to help with flood control and water quality. While beaver can be pesky in our expanding human habitats, they are much needed in our natural habitats.

Even the most lowly, annoying-to-us critter has a role to play in our ecosystem. While no one wants wildlife in our homes, understanding the importance of each species in Jackson Hole can enhance our enjoyment of the out-of-doors, even in our own backyard.

How to Nature Map Small Mammals:

Nature mappers can help record the use of habitats — both cultivated and wild — by many of our often unseen or unappreciated small mammals. Here are some tips for mapping a few rodents and related species:

Uinta ground squirrels are buffy brown, about a foot long, with short tails. They often sit erect near the entrance to their burrow holes or look like soft lumps of manure on the edge of roads, until they move. We particularly encourage notations on the First of Year (FOY) appearances in March and April and Last of Year (LOY) sightings in late July and early August.

Uinta Ground Squirrel

Our other ground squirrel, Golden-mantled ground squirrel, looks like a chipmunk due to two set of stripes on its back, but unlike chipmunks, it does not have stripes on its head or tail. These are mostly found in forests, rocky areas and some shrubby sites, particularly at higher elevations.

Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel

We have three species of chipmunks: all have stripes on their heads, backs, and to some extent down their tails. Least chipmunk is more likely in the sage flats and runs with its tail straight up. The tail is longer than its body. It is smaller and darker on its belly than the Uinta chipmunk, which is found more in coniferous forests or shrubby areas. Uinta chipmunk tends to have a lighter belly and a wider tail. Unlike the other two species found in Jackson Hole, Uinta chipmunks have a white outermost stripe along their backs (rather than a fairly distinct black or blackish-brown stripe), which is shown nicely in this Berkeley photo. Relatively more brightly colored, yellow pine chipmunk is also a forest species and has orange highlights. These can be very difficult to distinguish. Do your best, but when in doubt leave it out.

Three Chipmunks in Jackson Hole: Least (left), Uinta (middle) and Yellow Pine (right). Middle and right photos Wyoming Game & Fish Department (WGFD).

Northern pocket gophers by their nature are hard to see unless you are lucky. These gray, 8 inch animals have small eyes, tiny ears, and large front feet with noticeable claws. Their tunnels are obvious either as 3-4 inch rounded eskers left over from winter foraging or fresh mounds of soil about a foot wide and several inches high in summer. This “sign” can be used to indicate areas of abundance in sage flats, meadows or forest openings.

Pocket Gopher, Yellowstone National Park; Gillian Bowser; 1990

Mice, voles, and shrews are impossible to identify to species; therefore, we encourage nature mappers do their best record the groups. Mice have big ears and long tails. Voles have smaller ears and shorter tails and look relatively compact compared to mice. Shrews, which are a separate family, have elongate pointed heads with small eyes and ears and many teeth to eat their prey of insects, earthworms and the like. Tails vary in length. Our common species is masked shrew. We do not have moles in Jackson Hole.

Mouse (left), Vole (middle), and Shrew (right).

Beaver can be distinguished from their relative muskrat by their flat vs. rat-like tails seen while swimming in water. While both have rich brown pelts, beaver are usually bigger with a flatter head and are found among willows or other woody plants, which they use for food and dam building. Muskrats use soft-stemmed cattails, reeds and rushes to form their mounds and for food; therefore, they are more likely in wet meadows and marshes.

Beaver (left) has a flat tail while its relative, the Muskrat (right), has a rat-like tail.

Red Squirrels: Many people recognize the wide-eyed, bushy-tailed red squirrel found in forests and porches. Often we hear their chatter in the deeper forest. These tree squirrels are defending their territories and particularly their caches of cones. If you happen to see an active “midden,” pile of cone scales and stalks, take a point. This is an indicator of highly productive trees and possible pine marten habitat.

Red squirrel

by jhwildlife | Jun 7, 2018 | Blog

Communications Manager – Job Description

About Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation

For 25 years, the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF) has helped our community to live compatibly with wildlife – by working collaboratively with landowners and public land managers to remove or improve fences, by empowering citizen naturalists to build our local knowledge base, and by acting to make roads safer for people and animals. Our grassroots, volunteer-supported model and hands-on approach reflects our belief that enduring conservation emerges from an engaged and committed community. Strategically, we are focused on preserving and improving the migration corridors that sustain wildlife and connect communities.

Summary of Main Responsibilities

The Communications Manager drives JHWF’s internal and external communications. The Communications Manager reports to the Executive Director, is a member of the organization’s management team, and is responsible for providing input that guides JHWF’s strategic actions. The Communications Manager connects JHWF with the public through visual and verbal storytelling, designs informative and creative communications pieces, delivers public presentations, and works to expand and diversify our support base. This position will help to establish and implement communications objectives; develop, edit and share content; and manage JHWF’s social and digital media tools. The right candidate will exhibit strong writing and interpersonal skills and will have the ability to interpret scientific concepts and conservation strategies for a varied audience. Possessing a good eye for visual presentation and design will also be a valuable characteristic demonstrated by the ideal candidate.

The essential functions include, but are not limited to, the following:

Content Creation and Public/Media Outreach

• Develop, curate and distribute content for annual print newsletter, monthly email campaigns, weekly blog, and timely videos.

• Design and prepare marketing collateral, press releases, reports, and presentations.

• Manage and organize digital assets.

• Develop engaging materials and tools to drive support for JHWF programs.

• Compose and emphasize key messages to be shared with staff, board and public.

• Design strategy for JHWF’s presence at external events and represent JHWF as needed.

• Serve as first point of contact at JHWF, via managing main phone and info@jhwildlife.org email account.

• Develop positive relationships with media and respond to media inquiries.

• Work with outside consultants and resources to place op-eds, stories and articles in a variety of publications.

Digital and Social Media

• Develop strategy and regularly publish/update web and social media content to support JHWF’s programs, activities and events.

• Maintain the JHWF’s website and blog.

• Maintain the JHWF’s social media channels; track and evaluate engagement to maximize reach. Utilize paid advertising opportunities as deemed appropriate.

• Monitor and constructively engage in relevant online conversations.

• Advise, train, and support staff on use of digital media tools.

• Ensure communications infrastructure is maintained, including server, website, etc.

Development and Organizational

• Contribute to long-term planning with management team and board to increase impact.

• Support JHWF development efforts by crafting donor and donor prospect communications, informational pieces and fundraising campaigns.

• Process donations, gift entry and bank deposits.

• Manage contacts database (Salesforce).

• Participate in programmatic work and contribute to organizational activities as needed.

Required Qualifications

• Minimum of two years of communications strategy and implementation experience including strong experience with digital media, social media, web design, publishing and partner relationship management tools.

• Bachelor’s degree in related field.

• Familiarity with wildlife conservation, wildlife management, large-landscape scale conservation and citizen science.

• Passionate about conservation, wildlife, volunteerism, connecting people to nature.

• Ability to work independently, set priorities and see projects through to completion.

• Ability to contribute positively within a collaborative team environment.

• Outstanding written and verbal communication skills.

• Flexibility to experiment to attain new, better strategies, approaches, work products and solutions to challenges.

Preferred Qualifications and Experience

• Experience working in a nonprofit or philanthropic organization (conservation/wildlife especially).

• Salesforce, WordPress, Adobe InDesign, Illustrator, and Photoshop experience.

Compensation: salary, including benefits, based upon experience and skills.

Benefits include: Medical, dental, life and short-term disability insurance; paid sick leave, holidays and vacation.

To Apply: Please email a letter of interest and résumé with three references to: Kate@jhwildlife.org. For more information, visit: www.jhwildlife.org.

Application Deadline: June 24.