by jhwildlife | Oct 10, 2019 | Blog

By Kyle Kissock, Communications Manager

2.9 billion birds.

Let that number sink in. That’s how many less birds inhabit North American skies, forests, and cityscapes today, than did in 1970.

You probably saw the (now viral) scientific study that was released last month. It exposed an avian population in free-fall in the United States and Canada over the last five decades. Experts are referring to the near 40% decline detailed in its conclusions as a “full-blown crisis.”

A study recently showed North American bird populations undergoing rapid declines. What can we do to help?

In the wake of the study’s release, I found myself feeling a little helpless. I suspect I wasn’t alone. I understand that from a scientific perspective, losing birds has broader implications for ecosystem health. But more personally, identifying the sparrows, nuthatches, and cardinals of my childhood backyard was one of my first authentic connections to the natural world. The arrival of colorful warblers in the springtime, the flocking of chickadees to the feeder during a winter snowstorm. The thought growing up without these backyard birds elicits a visceral reaction; to me, their simple presence still inspires awe and wonder. I believe birds make our world a richer place.

As a community of wildlife-enthusiasts, I think we have rights to be concerned. But a month out from the sobering news of this study, I’m also trying not to feel helpless. It’s true that reversing this trend and effectively combating decline of this magnitude will take intentional, global action. But what’s stopping us from personally working to save one, two, or three birds a year? For example, Nature Mappers report bird strikes on windows nearly every month . . . is there something we can be doing better that can make an immediate impact?

Let’s starting by taking the causes of avian decline case by case. Then, I urge us to consider if there are steps we can take today to lessen our impact on our avian friends. According to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service the top three causes of bird deaths in the United States are as follows:

- Cats: 2,400,000,000 bird deaths annually

- Collisions with buildings (glass): 599,000,000 annually

- Collisions with automobiles: 214,500,000 annually

Cats

What can we do? – Consider indoor cats. When young birds leave their nests, there is a period of days when they cannot sufficiently fly to escape predators. These fledglings stand virtually no chance against prowling prides of suburban felines. Many of us have pet cats ourselves. All of us know somebody who owns a cat, or cats. These numbers do not mean we should give up our beloved cats. They do mean that if we’re serious about being a good neighbors to local wildlife, we should be aware of the impacts “outside cats” have on nesting bird populations.

Automobiles

What can we do? – Drive a reasonable speed and pay attention to the road. Do not crash your car trying to avoid a bird. Do remember, the faster you drive, the less time any animal will have to react to avoid being smashed by your vehicle. Not carelessly exceeding the speed limit in known wildlife-habitat is a great way to keep yourself and animals safe!

Window Strikes (The single easiest way to help birds)

What can we do? – Birds collide with windows because they see reflections of sky, vegetation, or sometimes themselves. If you have windows that regularly experience bird strikes, please consider one of several mitigation techniques.

- Window decals – These can be purchased on Amazon here as well as from decal-specific sites here or here. Find a decal that works for the aesthetics and functionality of your window. Recommended spacing for decals is small enough that birds can’t fly between them, but anything is better than nothing. Personal note: I had “problem windows” in my apartment before adding a few clear, window decals. My evidence is unscientific, but my problem windows have experienced far less bird strikes over the last year. I wish I had acted sooner.

- Write-on-glass markers – Check out this video to see how to mark your window with glass markers so that they are apparent to birds!

- Vertical blinds and or screens – A screen on the outside of a window can minimize reflective potential of the glass. Vertical hanging blinds on the inside of a window can serve the same purpose.

Click here for more mitigation techniques.

So where does this leave us? Admittedly with a long way to go. But we also know that many people coming together, to make small changes really can result in outsized impacts. As acommunity that pledges to live compatibly with our wild neighbors and reduced human impacts on wildlife, I believe it’s our responsibility to consider everything from moose to Song Sparrows, in the course of our daily lives.

If you find yourself acting to minimize your impacts on birds on the heels of this report, please let me know at kyle@jhwildlife.org. I’d love to share your story!

Note: In the past, Nature Mappers have coded mortalities from bird-window strikes as “Accidents” in the NMJH database. To be more specific going forward, the correct coding will be “Serious Injury” with a prompt to make comments in the “Notes” field to record a bird-window strike.

by jhwildlife | Sep 19, 2019 | Blog

Choke Cherries are favorites of birds, bears and small mammals. Birds can become “tipsy” feeding on the fermenting, fall berries.

As wildflowers fade and grasses dry, wildlife depend on the more permanent presence of woody plants to get through the next several months. Lowly shrubs are key for survival. They offer up colorful fruits and still-green leaves and stems providing essential fats and carbs for bird for migration and mammal hibernation for winter. And dried fruits and bare twigs contain sustenance throughout winter for critters above ground.

Here are a just a few examples of shrub and animal connections. Research on which animals species use which plants is relatively sparse for our region. Your Nature Mapping observations noting what animals are using which shrubs and how are helpful information.

Bears eat berries. In summer huckleberries are a favorite and right now they are into hawthorns—the main reason for the recent closure of the Moose-Wilson Road. Of course bears consume many other fruits as well.

In late summer, thimbleberries stand out amidst broad green leaves that thrive in the moist shade of streamside forests. Once red, the raspberry-like fruits disappear within a day or two—who ate them? Perhaps birds, squirrels, chipmunks, but no one knows for sure.

In late summer, tanagers, grosbeaks, vireos, robins, and waxwings search hillsides and backyards for service berries, chokecherries, and now ripening hawthorns. In town they will look for planted crabapples (bears will too!). Red-stemmed dogwood fruits are particularly high in fats needed by migrating birds.

Serviceberries serve as late summer food sources for birds like Waxwings, Tanagers, and Robins.

While some bird species will keep flying south, the local abundance of American Robins and Cedar Waxwings will depend on the amount of fruit persisting over winter. Rosehips are particularly durable. Leftover fruits come spring give an added boost to returning migrants.

Bright orange elderberry and mountain ash are particularly popular with birds, small mammals, bears, elk, and moose. Some people have said these berries are poisonous because they see so many untouched and often on the ground. Elderberries have a high alkaloid content—we people must always cook the berries first. However, they are preferred foods of many critters. Most likely, the plentitude of berries keeps them from all being consumed right away. Also, these fruits become more tasty with a frost or two which brings out the sugars. It is possible for birds to become tipsy on fermenting fruits.

Studies indicate that antioxidant compounds in polyphenol and anthocyanin rich fruits help reduce the extreme metabolic stress of migrating birds. Anthocyanins show up as a deep purple maroon color.

Hawthorne berries are a favorite of bears. They grow in abundance along Moose-Wilson Road.

After the rut in late fall, moose congregate, often by the dozen, on Antelope Flats. They are eating the nutritious green leaves and twigs of antelope bitterbrush, not the pungent silver twigs of sagebrush.

Moose also depend on the cover and browse of willows stands. And as those with gardens know, moose will zero in on red-stemmed dogwoods and roses in the landscape.

Sagebrush grows in abundance in Grand Teton National Park. Wintering moose, however, are largely grazing on the intermixed antelope bitterbrush.

Leaves and twigs, as well as the dense twiggy habit of sagebrush provide food and cover for greater sage-grouse winter long.

Bighorn sheep, along with deer and elk, will preferentially browse a low fuzzy shrub called winterfat on dry knolls. Winterfat contains 10% crude protein in winter.

Townsend’s Solitaire, related to robins, particularly savor the evergreen cover and bluish “berries” of juniper. So look for them on dry hill sides with an abundance of Rocky Mountain juniper, such as the flanks of Miller Butte.

Juniper Berries are a food source for the Townsend’s Solitaire, a relative of the American Robin

All our wildlife depends on plants. Take a closer look at these connections, and please keep on Nature Mapping!

By Frances Clark

Frances will be presenting a program on “Teton Shrubs: ID Tips and Wildlife Values” Tuesday, Sept. 24, at 6 p.m. on at the Teton County Library.

by jhwildlife | Aug 27, 2019 | Blog

By Kyle Kissock, Communications Manager

Thirty JHWF volunteers partnered with local property owners and families to help removed burned fence at Hoback Ranches. The community is installing over 10 miles of wildlife-friendlier fence in this critical migration corridor.

Not all wildlife-friendlier fence projects are created equal.

Rarely, for example, are Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation fence volunteers treated to homemade pastries, a full wash station, and unobstructed mountain views all in one project. And never before have we had the privilege of assisting a local community rebuild its wildlife-friendly infrastructure after a destructive wildfire.

But let’s start at the beginning.

Formed in 1976, the Hoback Ranches subdivision was one of the first of its kind in Wyoming. It’s a community with a history of resiliency; until recently, Rim Road, the artery which connects the Ranches to Highway 89, was unplowed in winter. Year-round residents had to snowmobile or ski the entire distance up the Rim Road from the Highway to reach their homes. Apparently, there was a surprising contingent of these hearty locals who did.

Wildlife conservation has also been a core values of Hoback Ranches since its founding. The Ranches are located in the Hoback to Red Desert migration corridor for mule deer, as well as a prominent pronghorn migration pathway. An elk feed grounds to the south means migrating elk are community regulars. According to long-time resident Bill Conley, the area also provides habitat for abundant badgers, “chiselers,” coyotes, jack rabbits, snow shoe hare, and even more seldom-seen critters like Great Gray Owls, black bears, and the occasional mountain lion or wolf. An abundance of water and willows, large lot sizes, and hunting restrictions all add to the area’s high habitat value.

The remains of a moose that became entangled in a Wyoming fence during the winter of 2018/2019. Wildlife-friendly modifications to fence lines can prevent human-cause mortalities like this one.

To make life easier on wildlife, Hoback Ranches recently collaborated with Wyoming Game and Fish on a grant to fund replacement of the 19 miles of barbed-wire fence that ran the length of the subdivision’s perimeter, with wildlife-friendlier fencing. Wildlife-friendlier fencing generally contains a smooth-wire component, and/or abides by dimensions which allow wildlife to travel over or under wires with minimal risk of entanglement. The grant was accepted and funded by the Jonah Interagency Mitigation and Reclamation Office and the Pinedale Anticline Project Office.

However, replacement of the existing barbed-wire had scarcely begun before last October’s human-caused Roosevelt fire swept through the subdivision. The fire obliterated homes and consumed the natural landscape, along with the beginnings of the recently-funded wildlife friendlier fence modifications.

The hilly topographic character of the landscape here made removing wire somewhat challenging but added to the stunning scenery of project site.

For those who haven’t traveled to the Roosevelt Fire burn zone, the full extent of the fire’s impact on the landscape is jaw-dropping. By the time the massive 61,000-acre blaze ran its course, it destroyed 50 houses in Hoback Ranches, nearly half of which belonged to permanent residents. Much the conifer and aspen growth that covered the Ranches’ hills now stands charred, and many of the houses that survived the blaze sit exposed in the vast expanse of blackened timber and sage.

But what also stands out is the regrowth. Less than a year from the fire, green grasses, patches of fireweed, and fields of knee-high purple lupine coat the burnt understory in midsummer. The human regrowth Hoback Ranches is experiencing is also apparent. The drone of power tools, raising new homes and clearing wasted timber and roadways, echo across the Ranches hillsides. Regrowth emergent, resiliency in action.

In July, volunteers from the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation were asked to help remove the old perimeter fence that had been destroyed by the fire. Because most of the subdivision is bordered by actively grazed land, fencing here is still necessary, and miles of fence downed by the fire need to be removed before the wildlife-friendlier fencing can installed. Furthermore, even in its dilapidated state, downed wire presents an entanglement hazard for passing wildlife.

This wash station came in quite handy for cleaning soot off our bodies and clothes. Staying clean was quite impossible.

The first step of the process was separating burned wire from charred fence posts. Volunteers developed a system of removing staples from the posts to free the wire, then spanning into human “disassembly lines” to walk the loose wires towards our wire-winder. Wire ends were tied to the winder, which provides a mechanical advantage in coiling large lengths of fencing into manageable spools. These smaller spools could then easily be removed from the site in the beds of pickup trucks. In areas of steep terrain, where burned trees and brush were too dense to operate the wire-winder, volunteers were forced to roll fencing by hand. It was a dirty, sooty job, but it was rewarding. Generous Hoback Ranches residents provided us with cookies, brownies, and a wash station (the same type that wildland firefighters use) we found to be icing on the cake.

Barbed-wire rolls generated by the winder. By the time we had finished, JHWF volunteers had partnered with residents to remove three miles of wire in two field-days of work.

After two full days of work, JHWF volunteers had partnered with landowners to remove three miles of dilapidated wire. 30 JHWF fence team volunteers had contributed an impressive 298 total volunteer hours to the effort. With a little more labor, Conley and fellow homeowners hope to complete the project by next spring.

Staff and volunteers of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation were honored to be made a part of this community’s rebuild, even in our own small way. We were also grateful to get to experience the scenic beauty of the area which still very much remains intact after the fire.

A sincere thank you to all who were a part of this truly special experience!

It’s hard to beat open fields of blooming lupine under Wyoming skies!

If you’d like to get involved with volunteering on our fence team in the future and are not already on our mailing list, email info@jhwildlife.org to sign up!

by jhwildlife | Jul 26, 2019 | Blog

Guest Blog by Ben Wise | Biologist – Wyoming Game and Fish

Pronghorn Antelope can be found throughout the grasslands and sagebrush landscapes of the valley and have a long history of finding ways to survive in the harsh landscapes of western North America. Pronghorn are are the last remaining member of the family Antilocapridae, with their closest living relatives being giraffes and okapi (both of Africa) and are one of the last remaining unchanged North American terrestrial mammals from the Pleistocene era. Pronghorn are the fastest terrestrial mammal in North America and evolved over-sized heart, trachea and lungs to enhance the ability to reach speeds of up to 55 mph over short bursts and sustained running at greater than 35 mph for four miles or more. Their long, light skeletal structure reduces stress on joints during sustained sprints and their hooves have large cartilaginous pads that act as shock absorbers while running over rocky, uneven terrain. This incredible speed was essential to evade prehistoric North American predators including two species of cheetahs, dire wolves, short faced bears and saber-toothed cats as well as modern predators including coyotes, mountain lions and bobcats. Other adaptations essential to survival on the open grasslands include incredible eyesight due to oversize, protruding eyes (roughly the same size as an African elephant) that allow them a 320 degree field of vision and the ability to detect movement up to 4 miles away. Hollow hair which is both light weight and incredibly efficient for both warming in the winter and cooling in the summer is also easily pulled out, allowing pronghorn an additional line of defense if caught by a predator. Finally, pronghorn antelope derive their name from the unique forked horns that both male and females grow, with males producing much larger horns. These horns are a combination of both horns and antlers with interesting qualities of both. True antlers are made of bone, grow throughout the spring and summer and are shed in the late winter of each year. True horns posses a bony core over which dense keratin grows and neither the bone or the outer core is shed during the life of the animal. Pronghorn are unique in that they grow a black keratinous sheathe over a bony core (similar to a horn) and after the breeding season each fall, shed the sheaths and begin regenerating another set of sheaths for the following year (similar to antlers).

Every spring between 300-400 pronghorn antelope migrate from the windblown sagebrush flats of the Green River Valley, following the Gros Ventre River drainage down to Grand Teton National Park and surrounding lands to give birth and raise their offspring. As winter approaches, these hardy individuals with four month old fawns in tow leave the Jackson valley, often enduring early fall snow that has inevitably began accumulating on the mountain pass that separates their winter and summer habitats, and retrace this “Path of the Pronghorn” as they have done for millennia.

Pronghorn derive their names from short horns that both males and females grow. Photo: Mark Gocke

by jhwildlife | Jun 24, 2019 | Blog

Guest Blog by Sarah Hegg | Biologist – Grand Teton National Park

The American Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) is one of the Endangered Species Act’s (ESA) most remarkable success stories. Grand Teton National Park was an integral part of their recovery in the Jackson Hole area.

Peregrine Falcons are cliff-nesting raptors that mainly eat other birds. They are perhaps most famous for their speed. Biologist have clocked peregrines at speeds of up to 200 mph, speeds that rival race cars. Along with their speed, their extraordinary aerial acrobatics, rapid diving, and graceful soaring make them one of the most impressive birds to watch. The lower elevations of the major canyons in Grand Teton National Park provide extensive opportunities for cliff-nesting and diverse habitats for foraging.

With the introduction and use of the pesticide DDT in the 1940s, many bird species, especially predatory raptors, experienced drastic declines throughout North America. Peregrine Falcons were among the birds most affected by DDT and its toxins. It is believed that peregrines were almost completely extirpated within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem by the 1960s.

Peregrine Falcons were listed under the ESA as endangered in 1970. The restriction and banning of DDT, along with other organochlorine pesticides within North America, in combination with habitat protections and a reintroduction program helped contribute to the recovery of Peregrine Falcon populations. In 1980, efforts to reintroduce Peregrine Falcons to Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks were initiated locally by The Peregrine Fund, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, and the U.S. Forest Service. These local efforts were in conjunction with similar efforts elsewhere in the Greater Yellowstone Area and western United States.

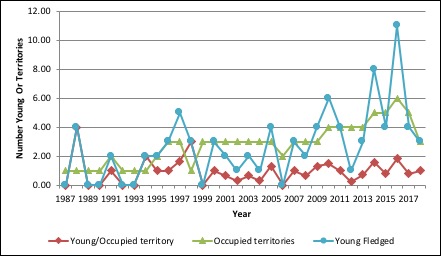

To reintroduce Peregrines in the park, large hack boxes (5’ x 4’ x 3’) were built using plywood sides, a barred metal front and a gravel floor. These hack boxes were placed at several sites within the park and Jackson Hole. Between 1980 and 1986, 52 fledgling falcons were released at 3 different hack sites. Several captive-bred peregrine chicks were placed in the hack boxes each year and fed multiple times daily through a remote feeding chute so the young falcons could be fed without associating food with humans. When the chicks were old enough to fly, the bars on the front of the hack boxes were gradually removed. The first wild nesting attempt in the park was documented in 1987 near Glade Creek, which was also the location of the first successful wild breeding occurrence in 1988.

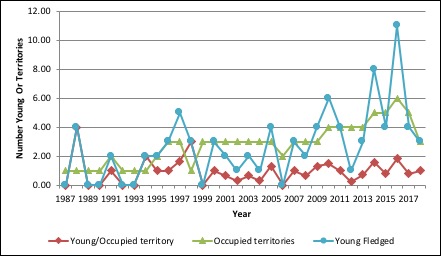

Annual peregrine falcon reproductive data in Grand Teton National Park, 1987-2018.

Peregrine Falcon populations have slowly recovered throughout North America and were removed from the ESA in 1999. Each year since 1987, park biologists conduct surveys of known and potential peregrine territories to document the number of occupied territories and their reproductive success. While the number of territories has gradually increased, reproductive success is still fairly low and can vary greatly from year to year.

One of the new territories established was in lower Cascade Canyon in 2010. This eyrie (the name for a peregrine nest) is located near Baxter’s Pinnacle, a popular rock climbing route. This area is thought to have been historically occupied in the early 1900s. Peregrine falcons are very sensitive to human disturbance. They will abandon their nest to defend their territory, which can lead to nest failure and low reproductive success. Since 2011, the park has established a closure for the Baxter’s Pinnacle climbing route and its descent gully area each year when and if biologists confirm the territory is occupied (typically sometime in April) and lasts until the pair fails or the young successfully fledge (generally mid-August). In addition to protecting young Peregrines, this closure also helps to protect climbers. Peregrine Falcons are fiercely territorial and aggressive birds, especially while nesting and incubating eggs. They become even more protective after their chicks hatch. The bird’s speed and aggressive territorial behavior pose a safety risk to climbers who could be knocked off the route and injured.

The Baxter’s pair have successful fledged young, six of the eight years that the territory has been closed, and is one of the most consistently successful Peregrine territories in the park. The support from the climbing community by respecting this closure area is crucial for the falcon’s continued success, and is greatly appreciated. This example of cooperation helps the park carry out its mission of preserving native wildlife and habitat while providing enjoyment and recreation opportunities.

Numbers in Grand Teton

- In 2018 park staff monitored 8 known and recently active territories, 3 of which were occupied.

- The 32-year historical average for successful occupied territories is 47%, and the recent 10-year average is 60%.

- The 32-year historical average productivity is 1.53 young per breeding pair, while the recent 10-year average is 1.77 young per breeding territory.

- The maximum numbers of peregrine territories occupied is 6, and the maximum number of young fledged is 11, both occurring in 2016.

Identification

- Slightly smaller than a crow

- Black/dark gray “helmet” and a black wedge below the eye

- Uniformly gray under its wings. (The prairie falcon, which also summers in Grand Teton, has black “armpits”)

- Long tail, pointed wings

Habitat and Behavior

- Near water, meadows and woodlands, cliffs

- Nests on large cliffs over rivers or valleys where prey is abundant

- Resident in the park March through October, when its prey—primarily songbirds and waterfowl—are abundant. Migrates to Mexico or even further south for winter

- Lays 2–4 eggs in late April to mid-May

- Chicks begin to fledge in late July or early August

- Dives at high speeds (can exceed 200 mph/320 kph) to strike prey in mid-air

Cover Photo by C. Adams

by jhwildlife | Jun 6, 2019 | Blog

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

“Preserve and protect the area’s ecosystem in order to ensure a healthy environment, community and economy for current and future generations.” – Teton County Comprehensive Plan’s Vision Statement, adopted 2012

In July 2019, the Jackson Town Council and Teton County Board of County Commissioners voted to add to a November, Specific Purpose Excise Tax (SPET) ballot measure that will allocate (if voters approve) $10M for wildlife crossing solutions at sites prioritized within the County’s Wildlife Crossings Master Plan.

While there are many worthwhile and necessary projects on the slate, we believe that wildlife crossing solutions address the vision of our Comprehensive Plan (quoted above) precisely, warranting commensurate investment. Oddly, and despite the fact that the community has repeatedly stated that wildlife is a paramount value, the community has had very few opportunities to voluntarily invest in the preservation of wildlife or our ecosystem. In the case of the SPET, the burden of that investment is shared by both local residents and tourists. That cost-share for the benefit of wildlife makes sense, since our local economy rests on the health of a globally significant ecosystem that requires wide-ranging stewardship.

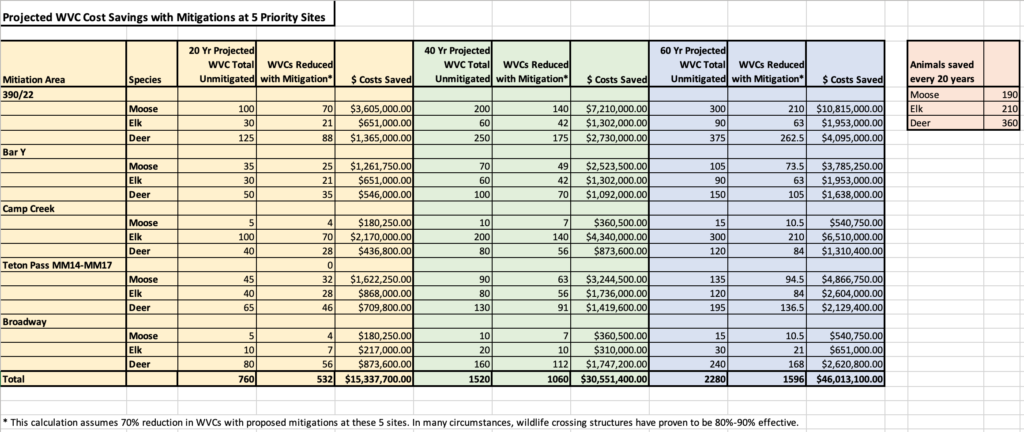

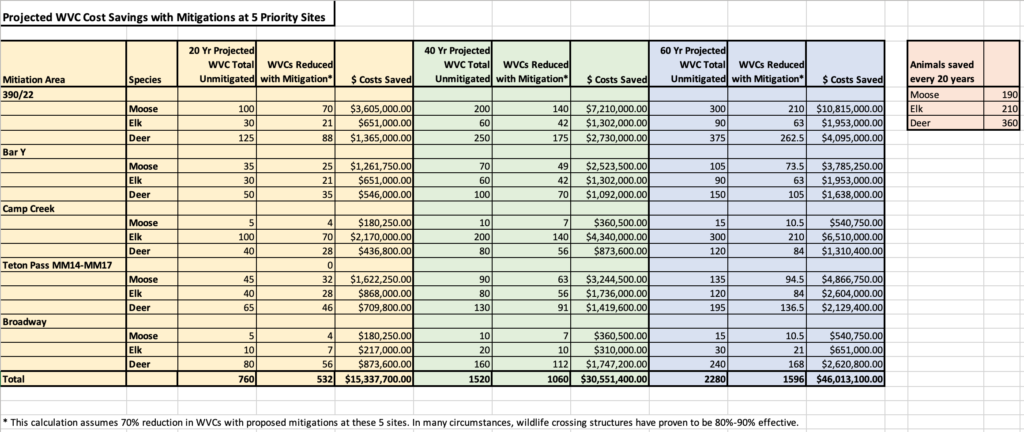

What about the question of “how much?” While we intuitively value “saved wildlife,” safer highways and connected habitats, those intangible benefits are difficult to measure. Most cost-benefit analyses look at the tangible costs of wildlife-vehicle collisions (WVC) to ungulates (many other small and large animals are hit by cars in our valley, including hawks, eagles, owls and osprey). Those costs include vehicle damages, bodily injury, carcass removal/disposal and the “game value” of the animal as assigned by the Wyoming Game & Fish Department. The “wildlife-vehicle collision costs per species” varies from state to state, but for our purposes in Wyoming, we estimate those costs as follows:

Moose = $51,500

Elk = $31,000

Deer = $15,600

The differences in these costs correlates to the size of the animal and the related severity of a collision. To analyze the efficacy of wildlife crossing structures at these specific prioritized sites, we project the current 5-year WVC trends (from the Teton County Wildlife-Vehicle Collision Database that we manage) into the future and assign a WVC Cost Per Species as listed above. We then calculate the cost saved through estimated WVCs reduced. None of these numbers reflect the value of moose, elk or deer to our tourism economy, nor do they reflect the value of the animal within our particular ecosystem or community. Jackson Hole values moose and elk extremely highly, partly due to their intensely-monitored populations, but also because they are iconic symbols of this wild place, and veritable neighbors to many around the valley.

Wildlife crossing structures have been shown to reduce ungulate WVCs by 80-90% when appropriately fenced, but they are not the only or best solution everywhere. In some cases, the geologic/geographic/hydrologic properties of a location preclude effective structural solutions. In other places – especially roadways of 40 mph or lower – a variety of tools can be deployed to positively affect WVC-reduction at a good “cost-per WVC reduced.” Those tools are being used in the town of Jackson, along the WY390 route, and soon in the town of Wilson to slow drivers and increase the probability of avoiding collisions with animals. We use the same cost-benefit formula to assess the efficacy of any tool deployed in any location, enabling the best solutions based on the variables present at each site.

We feel that the four “top priorities” considered within this measure are best addressed with structural solutions. The spreadsheet below includes WVC projections and the economic value of WVC costs saved over 20-year intervals at five prioritized locations (WY390/WY22 intersection, WY22/Bar Y, WY189/WY181 Camp Creek/Hoback, WY22 Teton Pass West MM 14-17, and West Broadway in the town of Jackson – the non-structural solution in this mix). These numbers do not incorporate inflation, and while they are estimates based on current trends in each location, the extrapolated numbers (rounded for simplicity) do not consider changing population or distribution dynamics over time, which is likely to occur to some degree. Each site was analyzed as a two-mile stretch of highway, with the exception of West Broadway, which is a one-mile site. Click on the spreadsheet below to enlarge.

What we find is that appropriate mitigation measures installed at these 5 sites should pay for itself in WVC cost savings in about 20 years, and perhaps less. While appropriate mitigation measures at all sites will likely exceed $10 million dollars, if we conservatively assume that the measures we can take in these 5 locations will ultimately reduce current WVCs by 70% (recognizing some limitations in a few of these sites), we would save just over $15M in 20 years. After that 20-year period, future savings (an additional $31M over the ensuing 40 years of a structure’s expected 75-year lifespan) exceed the cost of the solutions implemented. That is a good use of public money, especially when considering that this public money is invested expressly to realize the vision of the County’s Comprehensive Plan. We aim to be conservative in our estimates as we place a high value on the efficient use of public funds.

![]() I hope that you will agree with Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and countless other community members that a $10M SPET investment in solutions for these sites is an extremely prudent investment for our community. It’s not always easy to measure the value of a publicly-funded item, but in this case, we can make an easy economic case for the value of our foresighted action. These actions, combined with other site-specific solutions elsewhere, will make our highway network safer for drivers and wildlife.

I hope that you will agree with Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and countless other community members that a $10M SPET investment in solutions for these sites is an extremely prudent investment for our community. It’s not always easy to measure the value of a publicly-funded item, but in this case, we can make an easy economic case for the value of our foresighted action. These actions, combined with other site-specific solutions elsewhere, will make our highway network safer for drivers and wildlife.

To learn more about WVC solution opportunities at many of the County’s prioritized sites, please review this Wildlife Crossings Master Plan Action Summary to which Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation contributed.