by jhwildlife | Apr 29, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

By Sarah Ramirez, Teton Raptor Center Research Technician

It’s nearly impossible to drive around the Jackson area without seeing a wooden platform attached to a powerpole or freestanding. This summer, Teton Raptor Center will utilize citizen scientists to monitor over 60 osprey platforms throughout Teton County (excluding Grand Teton National Park’s, as they monitor their own). These platforms will be checked once a month, starting in April and finishing in August, and will determine occupancy by Canada Geese and nesting productivity of Osprey. Data collected in past years by Nature Mapping Jackson Hole volunteers has been integrated into the ongoing Teton Raptor Center-led project.

In the last few years, Canada Geese have been nesting in osprey platforms in Teton County. Since they migrate into the valley weeks, if not a month, before osprey do, they generally nest beforehand and take claim to these platforms. Canada Geese prefer to nest in open, unobstructed areas, and these platforms most likely give their eggs/goslings a better chance against mammalian and reptilian predators. Teton Raptor Center has developed a nesting platform that tilts downward while the geese are looking to nest, and are pulled flat once the Osprey return to the valley. With our monitoring activities, it is important to note how many and which nesting platforms are being used by Canada Geese, so we can correctly place tilted platforms in needed areas.

Keep an eye out for osprey nesting this season! Regardless of where you see Osprey, Nature Mapping their locations and behaviors can help us learn more about their needs and preferences, ensuring that they thrive here into the future.

by jhwildlife | Apr 20, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

While the saying has had many applications over the years (its first recorded use dates back to the 16th century!), “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” can be taken quite literally when it comes to bird banding. Having a bird in the hand allows researchers to take quantitative measurements and make up-close, detailed observations that, in most other contexts, would be difficult, if not impossible. What’s more, after multiple years of collecting such data, we can start to observe changes and trends within an avian population and, eventually, to make deductions about the health of the ecosystem.

This is largely the goal of the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program. Begun in 1989 by the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), the program is a cooperative effort to collect standardized data on North American landbirds. By increasing understanding of the factors that affect avian populations and their relationships, from a local to a continental scale, ecologists are able to make informed conservation and management decisions. Furthermore, the effectiveness of those decisions will be able to be measured once they have been put into action.

Beginning in June 2018, JHWF staff and volunteers will be leading banding efforts at two MAPS stations in the Jackson area. Both sites were started by the Teton Science School’s Teton Research Institute in 1991 and 2003 and were run by the Teton Raptor Center from 2014-2017. We hope to be able to contribute ongoing data for many years to come!

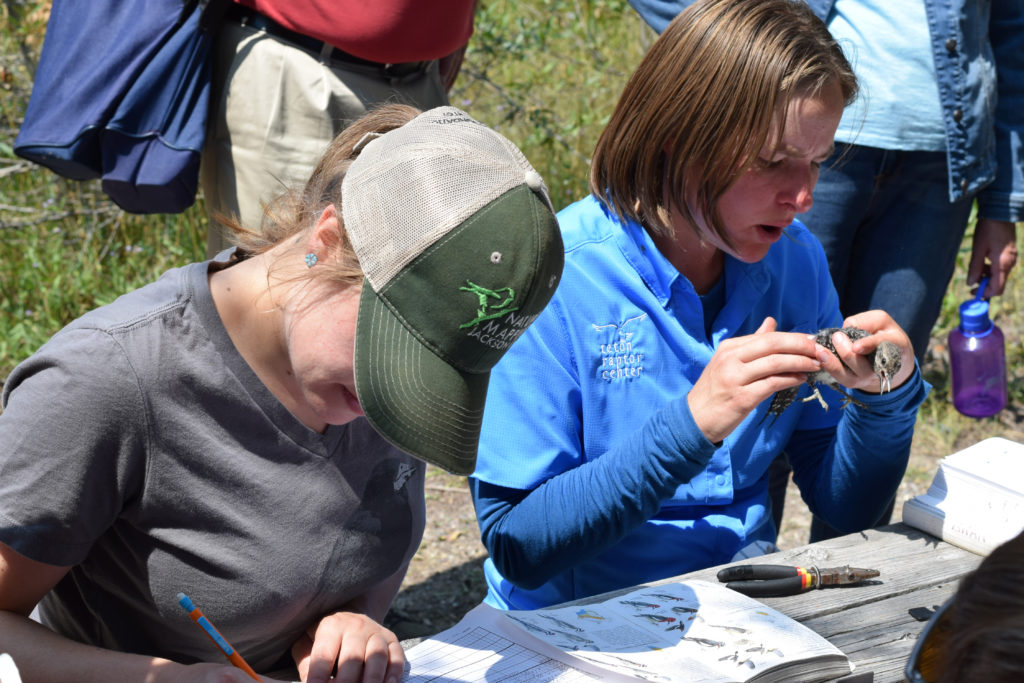

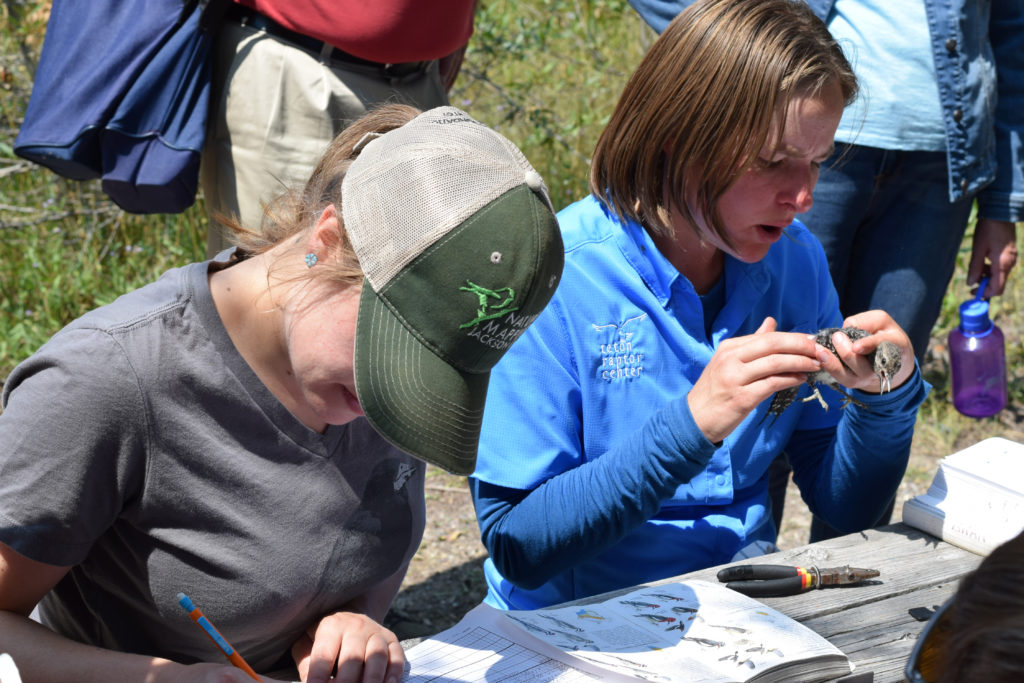

JHWF Associate Director Kate Gersh (left) records data provided by Teton Raptor Center’s Allison Swan (right) at a banding station in 2017. The two organizations worked closely during a transition year to ensure that the essential program would continue smoothly.

How does MAPS work?

MAPS stations use mist nets, placed at permanent locations within a designated study area, to safely capture birds. Banders extract the birds from the nests and bring them back to a centralized location, where they take various measurements and place a USGS-issued aluminum band on each bird’s leg prior to releasing it. Banding begins around sunrise and the nets are open for six hours during one day of every 10-day period. The season begins in May or early June, depending on latitude (that’s the first week of June for us, in Jackson Hole!) and runs through early August.

So what sort of data does one take from a bird in the hand?

After the species identification and band number (whether it is a newly banded bird or recaptured), the most important data we collect is the age and sex of the bird. Is it a young bird or an adult? Male or female? How exactly we deduce this depends on the species; however, many species of songbirds exhibit sexual dimorphism, meaning the males are visibly different from the females. During the breeding season, this is often most apparent in the bird’s plumage—males have on their “sexy plumage,” to help them attract a mate, while the females’ feathers are more subtle and subdued, to provide camouflage while they are on the nest.

A juvenile American Robin gets banded with a USGS-issued aluminum band with a unique number sequence. This will allow anyone who recaptures the bird in the future to identify it as the same bird!

Alternatively, by blowing on the bird’s abdomen to part the feathers, we can observe less obvious signs. In preparation for incubation, females will develop a bare patch on their breast and abdomen, called a brood patch, which allows efficient heat transfer to keep eggs and nestlings warm. In contrast, a male will develop a cloacal protuberance. A cloaca is the opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts of all vertebrate animals, regardless of sex, with the exception of most mammals. This orifice will swell as the breeding season approaches, allowing us to identify the bird as an adult male. In some cases, detail as subtle as wing or tail length is required to differentiate between males and females!

As with determining a bird’s sex, it is sometimes possible to figure out the age from the bird’s plumage, from the feather coloration and pattern and/or the shape and quality. The specifics depend on each individual species, but the basic idea is that a bird will have plumage distinctions as a juvenile (only recently having left the nest), a young bird still in its first year of life, and as an adult. Some species will retain certain feathers, usually in the wing feathers, that allow more detailed aging assessments to be made. The Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part 1, by Peter Pyle, is an invaluable tool that details information about individual species’ molt patterns and feather characteristics that assist in differentiating between ages and sexes.

As with any rule, there are, of course, exceptions. Generally, though, these are all pretty good indicators. That said, just as it’s good to use multiple clues when identifying a bird or any other animal in the field, so too is it good to use multiple measures when making age and sex determinations in the hand.

Plumage characteristics such as the red patch on the face, tail feather shape, and relative age of the wing feathers help identify this Northern Flicker as an adult male.

Additional measurements taken in the hand:

- Skull ossification – birds have hollow bones and their skulls are no exceptions. The skull develops in two layers, which are ultimately connected by small columns of bone, or “struts.” Upon leaving the nest, only the outer layer is completely formed and the inner layer progressively develops over the subsequent 3-12 months, leaving visible “windows” in the meantime. We are able to monitor this development and potentially use it or its completion to assist in aging the bird.

- Fat – birds’ fat stores are constantly fluctuating. While, during the breeding season, we wouldn’t expect a bird to be carrying much excess fat due to the constant flurry of activity, birds are able to increase their weight 75-100% by storing up fat in preparation for migration.

- Feather characteristics – is the bird actively molting? Is there wear to the flight feathers (wings and tail)? Does the bird have multiple generations of feathers?

- Wing chord – birds’ wings have a natural curvature to them that helps generate lift and allows them to be such effective fliers. We take this unflattened wing length measurement, which is a good indicator of the bird’s size, similar to height in humans.

- Body mass – we weigh the bird using a digital scale, recording the mass to the nearest 0.1 gram.

When able, we aim to take all of these measurements prior to releasing the bird. However, the safety of each and every bird is our priority and we are constantly checking in on the bird’s condition during the banding process. If the bird starts to exhibit signs of stress, we will let it go.

We are thankful for all the time and effort TSS and TRC have invested in continuing this long-term study and are excited to be able to contribute to this impressive data set. To learn more about the MAPS program and importance of long-term research, check out the MAPS project webpage. If you have any additional questions, please feel free to contact Kate Maley, the lead bird bander this season, at katelyn@jhwildlife.org or Kate Gersh at kate@jhwildlife.org. Happy birding!

A Cedar Waxwing perches nearby after being banded and released.

“

by jhwildlife | Mar 28, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

“I saw my first robin!” “I saw bluebirds!” “Did you hear the Sandhill Cranes the other day?” “The bears are out.” “Have you seen an Osprey?” “Not yet, should be here soon though.”

As March melts into April, Nature Mappers are excited for spring: we have new critters to see and hear. The wildlife data we submit become all the more interesting and important. This is the time of year we enter First of the Year sightings or FOY’s. We are measuring the natural pulse of spring. Some years, critters appear earlier, other years later, and some species reappear within days of the same date year after year. Your entries help track these annual variations. And if you don’t have the first sighting for the valley, you may well have the first in your area or the first for you! When you see these fresh arrivals, type “FOY” in the notes box of the data form to highlight your finding. Below are some species to look for with the earliest dates recorded between 2010 and 2015 in parentheses.

First of the Year sightings can be migrating birds or emerging or transient mammals. Stimulated by longer days, warmth, and the evolutionary coincidence of food, critters large and small mobilize. Midges, flies and true bugs begin to crawl and fly and become sources of protein for birds. Red-winged Blackbirds and Mountain Bluebirds arrive in the valley in March. In April, Common Nighthawks (4.11.13) swoop overhead through fresh insect hatches, along with Tree (4.8.14) and Violet-green Swallows (4.22.15). With more warmth (and insects), Yellow-rumped Warblers (3.6.10, 4.23.12), Vesper (3.24.12), Savannah (4.17.14), Chipping (4.21.15), and Lincoln’s (4.24.13) Sparrows show up in their various habitats. Warmer soils enable worms and the like to wriggle closer to the surface…within reach of probing beaks of American Robins, Long-billed Curlews (4.12.14), and White-faced Ibis (4.22.14). Anyone heard a Western Meadowlark yet?

Long-billed Curlew

As wetlands and ponds thaw, a variety of waterfowl are on display. American Wigeon (3.20.15), American Coot (4.6.10), Cinnamon Teal (4.8.14), Blue-winged teal (4.12.14), and Wood Duck (4.19.14) are in elegant breeding plumage. A flotilla of magnificent American White Pelicans (4.12.15) may be spied on the Snake River, with a Spotted Sandpiper pecking amidst the stones (3.22.12). Near by, the more ordinary granivores such as Brown-headed Cowbird (4.15.10) and Brewer’s Blackbirds (4.22.10) may flock in among Common Grackles (5.2.10), picking up old seeds and new bugs. Listen for the raucous calls of Yellow-headed Blackbirds (3.16.12) in marshes and skulking Sora (4.10.15).

American White Pelicans

Favorites to spot or hear include mammals and amphibians. Uinta ground squirrels should be emerging from their burrows. They went down last August for the long winter, and are one of the earliest hibernating rodents to reappear (3.26.18). Keep an ear out for their high-pitched whistle and then look for scampering. They emerge in time to feed coyote pups and summering Red-tailed Hawks. Least Chipmunks will pop up as well (3.23.12). We all thrill at the trill of Boreal Chorus Frogs (4.11.13) in neighborhood ponds and floodplain pools. “Cold-blooded,” or technically ectothermic amphibians, are a true indication of warming weather. Wandering Gartersnakes gain mobility from basking in the sun. Amphibians and snakes are an under-reported prize for Nature Mappers.

Red-tailed Hawk

Also, it is exciting to watch the world-renowned seasonal migrations of ungulates. When do the Wapiti begin to surf the green wave: moving by the thousands from the National Elk Refuge in sequence with the greening grass? Fresh forage provides essential calories and nutrition for females with soon-to-be-born calves. Hundreds of Pronghorn will arrive along the Path of the Pronghorn originating by Pinedale and weaving through the Gros Ventre into Jackson Hole toward the end of April. And where do the buffalo roam throughout the valley?

Where do the bison roam?

Some people consider April to be the off-season in Jackson. Nature Mappers know it is in fact the on season for wildlife. Enjoy entering your sightings that help us understand and protect these wonders of our valley.

–Frances Clark (Data compiled by Susan Marsh)

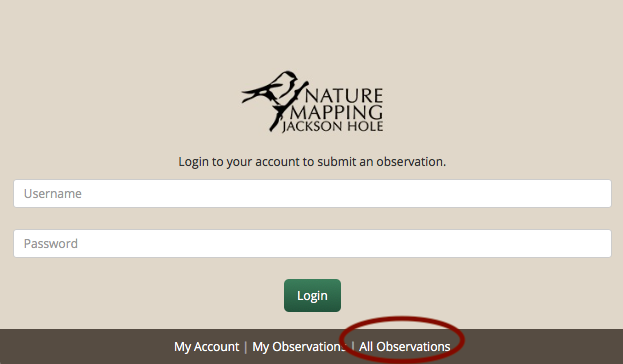

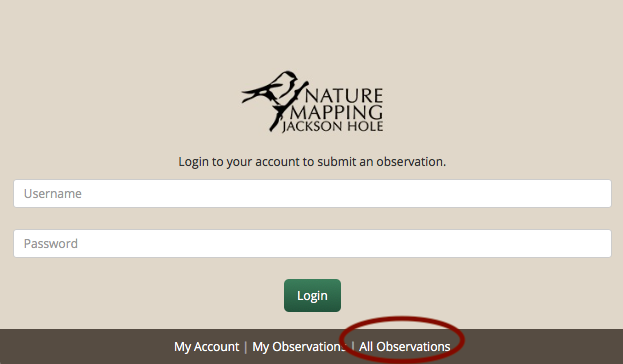

P.S. Curious what others have seen when? Click on the “All Observations” link on the bottom of the Nature Mapping JH Mobile Page. This is the list of all observations. You can filter by date, group, or species.

View All Observations

by jhwildlife | Mar 23, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

A new citizen science initiative will be launched this summer to better inform land management decisions in the heavily used Cache Creek drainage. The project is called the Neighbors to Nature: Cache Creek Study and will establish a four-way partnership between the U.S. Forest Service’s Bridger-Teton National Forest, Friends of Pathways, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and The Nature Conservancy’s Wildflower Watch.

Last week, project partners received word from the U.S. Forest Service’s Ecosystem Management Coordination staff in Washington, DC and their Office of Sustainability and Climate that Neighbors to Nature: Cache Creek Study was selected to receive a $25,000 grant from the Citizen Science Competitive Funding Program. Out of a total of 172 proposals received nation-wide, Neighbors to Nature: Cache Creek Study is one of just six proposals to be awarded funding.

The project will recruit a youth crew from Friends of Pathways (FOP), volunteers from the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation’s (JHWF) Nature Mapping Jackson Hole program, and volunteers from The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC) Wildflower Watch. These citizen scientists will collect, analyze and interpret plant, wildlife, and trail use data. The information collected will help establish a baseline of observations, as well as an effective and consistent method to gather and process this data over time. Forest Supervisor Tricia O’Connor said that this project will help achieve the goal for the Cache Creek area to serve as an outdoor classroom and deepen the connection between people and nature. She also noted that the project will help local managers by providing an accurate, scientific view of the plant and wildlife populations in the area, as well as improved information about recreation use.

The Friends of Pathways youth crew in Jackson, Wyoming will become citizen scientists for the National Forest

Approximately 10 species of native and invasive plants will be located and monitored by volunteers, and trail counters will be purchased and installed in key locations to observe how the area is being used for recreation. Some volunteers will directly observe and report on wildlife movements in the area, which can be used to evaluate how recreation use may be influencing wildlife behavior and inform management actions such as seasonal restrictions. Phenological observations such as leaf-out, budding, and flowering of plant species will help monitor the effects of climate change on plant communities and track invasive species. Data will then be analyzed and provided to the public at large and the U.S. Forest Service to inform future management decisions in the area.

ABOUT FRIENDS OF PATHWAYS

Friends of Pathways (FOP) works closely with the town, county and federal land management agencies to advocate for sustainable transportation and healthy recreation opportunities in Jackson Hole. Over the last four years its Youth Trail Crew has employed local high school students to work in partnership with the Bridge-Teton National Forest on trail maintenance, rehab projects, and data collection. This year the crew will be trained by Nature Mapping Jackson Hole to record wildlife they encounter while at work on the trails each day. They will also work with The Nature Conservancy’s Wildflower Watch to record phenological observations at key sites. Finally, they will help to collect usage data from trail counters and perform surveys to determine the types of users on the trails. For more information visit www.friendsofpathways.org

ABOUT THE NATURE CONSERVANCY

The Nature Conservancy’s Wildflower Watch invites volunteer citizen scientists to join in the study of how climate change may be affecting local plants and wildlife. Specifically our volunteers will record “phenology” or the seasonal timing of events – such as first flowering dates for several wildflower species. Powered by this research and education, we can work with public and private partners to prevent these impacts from becoming serious problems. This is a great way for individuals to take action to protect the places and creatures we love, beginning in our own backyard. The Nature Conservancy is a global conservation organization dedicated to conserving the lands and waters on which all life depends. Guided by science, we create innovative, on-the-ground solutions to our world’s toughest challenges so that nature and people can thrive together. In Wyoming, we are conserving lands, waters, wildlife and the Wyoming way of life. For more information, visit www.nature.org/wyoming.

ABOUT BRIDGER-TETON NATIONAL FOREST

The National Forests exist to care for the land and serve people by sustaining the health, diversity and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands for present and future generations. The core concept for management is the sustainability of resources to provide for the greatest good for the greatest number of people in the long run. As an integral part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the Bridger-Teton offers more than 3.4 million acres of public land for memorable wildlife, wild land, water, and diverse recreation experiences, notably during the winter. For the Neighbors to Nature project, the Bridger-Teton National Forest will help facilitator the partnership, provide guidance to ensure information will be useful to land managers, and assist with reporting and sharing information with the public. For more information, visit www.fs.fed.us/r4/btnf

by jhwildlife | Feb 28, 2018 | Blog, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

by Frances Clark

Two moose for the count by Gigi Halloran

First the stats, then the fun.

We had a windy day with off-and-on light snow, pretty good visibility, and temperature ranging from around 8 degrees to 18 degrees Farenheit in the Jackson area. We had 80 Moose Day volunteers on 33 teams covering 53 different areas. Unfortunately 14 teams struck out…no moose. This is always disappointing to the hardy observers, but “0” is important data, as well. We can get a feel for where the moose don’t go regularly over the years or the variability of their movements.

So where did the moose show up? Wilson once again had a high proportion: about 27 in different clusters and pairs. Grand Teton National Park from Kelly a bit north and west over through the Solitude development had approximately 25. Another eight were seen in the Jackson Hole Golf and Tennis area, including three spotted by Bryan, a guest staying with Randy Reedy. Bryan was getting into his car while Randy was out scouting! Volunteer time: five minutes. Jason Wilmot of USFS and partner saw 15 moose snowmobiling out to the end of the Gros Ventre road. Last year the team saw a remarkable high of 57 moose. Sarah Dewy and Steve Kilpatrick saw five moose in the Buffalo Valley area vs. 20 last year, and an overall low for that territory. The north and southern extremes of our count area had no moose. The total number of moose is 94, but we will double check for a couple of possible overlaps. This number is roughly average–87 is the average count, excluding two high years (2011 – 124 moose; 2017 – 172 moose –both years with alot of snow).

The most observed moose was one browsing and then sleeping along a row of willows just west of Stilson in Wilson. Over eight people reported seeing it there. We will count it once.

Eight mappers saw this moose, but it was counted once. By Amy Conway.

Other Highlights of the Day Besides Moose:

Several observers saw bald eagles in courtship. Bernie, Diane and Alice saw one pair of adults where the male bird was about 75% smaller than the female–this was an extreme example of a typical size difference in raptors females and males.

That team also sighted Townsend’s Solitaire and Snow Buntings on their territory south of Jackson. Morgan Graham took a picture of a Northern Shrike down in the same vicinity.

Trumpeter Swans, Barrow’s Golden-eyes, Mallards and mergansers were treats along the creeks and rivers.

Two groups of 15-16 elk were seen in different corners of Wilson. Pine Grosbeaks, European Starlings, woodpeckers, Great Blue Herons and coyotes also delighted Nature Mappers, especially those who did not see moose!

Thank you all for keeping your eyes out for moose in Moose Day 2018! The moose thank you, we at Nature Mapping Jackson Hole thank you.

Moose hiding but counted on Moose Day by Kathy McCurdy