by jhwildlife | Aug 17, 2018 | Blog, Wildlife Friendlier Landscapes

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

For 25 years, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF) has worked to reduce human-caused impacts on wildlife. One of our most visible programs, Wildlife Friendlier Fencing, began in 1996 when a small group of local citizens and JHWF founders organized group fence pulls on Saturdays. Over the course of the next two decades, hundreds of individuals (almost entirely volunteers) helped to remove or modify almost 200 miles of fence. There have been so many key contributors that it would be unwieldy to list them all here, but we recognize two of them today for their dedicated efforts in the field, and for their legacies that inspire our work well after their lives were ended much too soon.

Sue Colligan (left) and Greg Griffith were invaluable contributors to the Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program for many years.

Sue Colligan was the Executive Director of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation less than a decade ago, and all who remember her speak to her incredible dedication to the fence program. My personal recollection of Sue was as a member of an early incarnation of the Safe Wildlife Crossings for Jackson Hole group in 2011-2012. While I represented The Murie Center for that purpose, Sue advocated for wildlife on behalf of JHWF. At those meetings (in Vance Carruth’s living room), Sue used her voice effectively and with intelligent precision. I think she could say in 20 words what I convey in 100. Those who joined her on fence pulls have also spoken about her steady resolve to get things done for wildlife. When Sue’s illness took her life too soon, she left a legacy gift to JHWF to continue its essential work. With those funds, we have been able to purchase supplies for the Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program, and in 2018 we used funds left by Sue to purchase a work truck, which has been used extensively to support our Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program (it carries tools and gear to every project) and our Nature Mapping Jackson Hole program (it carries bird banding supplies, mist nets and gear to field sites weekly throughout the summer.)

The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation truck sits ready for work at a Wildlife Friendlier Fencing project site in front of the Tetons.

Greg Griffith is known to many in Jackson as the unstoppable engine of the Wildlife Friendlier Fencing program for many years. A car accident took Greg from us very prematurely, but rarely a fence project goes by without someone mentioning Greg – his specific project methods, his concern for other volunteers, his fierce commitment to doing what is best for wildlife. Stories about Greg are now the stuff of legend, except there’s no indication that any of the stories are exaggerated, as many legends are. If someone says that he once carried six full rolls of barbed wire down a mountain and across a raging river, I’d have to believe it. It must have happened just that way. While I never met Greg, I feel that I know him through these stories, through the many volunteers who were deeply affected by him. When Greg passed, friends from far and wide made donations to JHWF in his honor. Now almost three years later, we still receive notes and occasional donations that reference Greg’s impact. He improved the lives of people as he made our valley better for wildlife. With the donations made in Greg’s name, JHWF purchased a cargo trailer to house all of our fencing tools and other JHWF field supplies. In the near future, we will place a graphic wrap on the trailer that promotes the program and the work of the many volunteers who have contributed to its success over the years.

JHWF Board President Aly Courtemanch delivers the new cargo trailer to the JHWF office.

There are many people to celebrate in the history of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, likely none of whom really care to be celebrated. Many have done the work quietly and doggedly, on Saturdays, in the heat, in the rain. Whatever it has taken to get the job done. The legacy that follows all of these individuals is one of humble service to the wild community, to which we belong. May it ever be so.

by jhwildlife | Aug 15, 2018 | Blog

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

Across all of our programs, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation works to reduce human-caused impacts on wildlife. The negative impacts of roads are well documented, at least as it relates to vehicle collisions with large mammals. Less discussed is the impact on birds, although we know that impact to be significant. Teton Raptor Center admits more birds that have been struck by vehicles than any other source of injury. Some can be rehabilitated. Many cannot.

Raptor mortalities from vehicle strikes are not uncommon. On August 15, a hatch year Osprey was killed by a recreational vehicle on WY 22, not too far from a nest platform designed to support life for these magnificent raptors. The location of the collision was also not far from a digital message sign warning drivers that young Osprey may be on the road. The reason for the warning is that a fledgling Osprey may take a few weeks to take flight after initially leaving the nest. Its learning curve can include erratic flight, much like a toddler’s first wobbling steps. As many of us know in Jackson Hole, Osprey nest platforms are often near highways, and like many other raptors, Osprey also perch on electrical poles. Because of these realities, it is essential that drivers understand the potential for collisions with these beautiful birds during this short summer window, hence the educational messaging on the signs that typically alert drivers only to the likely presence of elk, deer or moose. Osprey are a dazzling, conspicuous bird, and just as you would slow your speed if you saw an elk in the highway right-of-way, alert drivers can greatly reduce the likelihood of collision with these raptors by temporarily slowing speeds to watch for imminent flight in these areas.

There is no guaranteed solution for eliminating raptor deaths on the roadways. Wildlife crossing structures that can facilitate ungulate movement over or under a highway are of no help to birds. Signage and education can help generally, and real-time actions, such as temporary digital messaging near nest sites, can alert many, if not all drivers to the presence of young birds. Every action counts. Give Birds a Brake!

by jhwildlife | Aug 14, 2018 | Blog

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

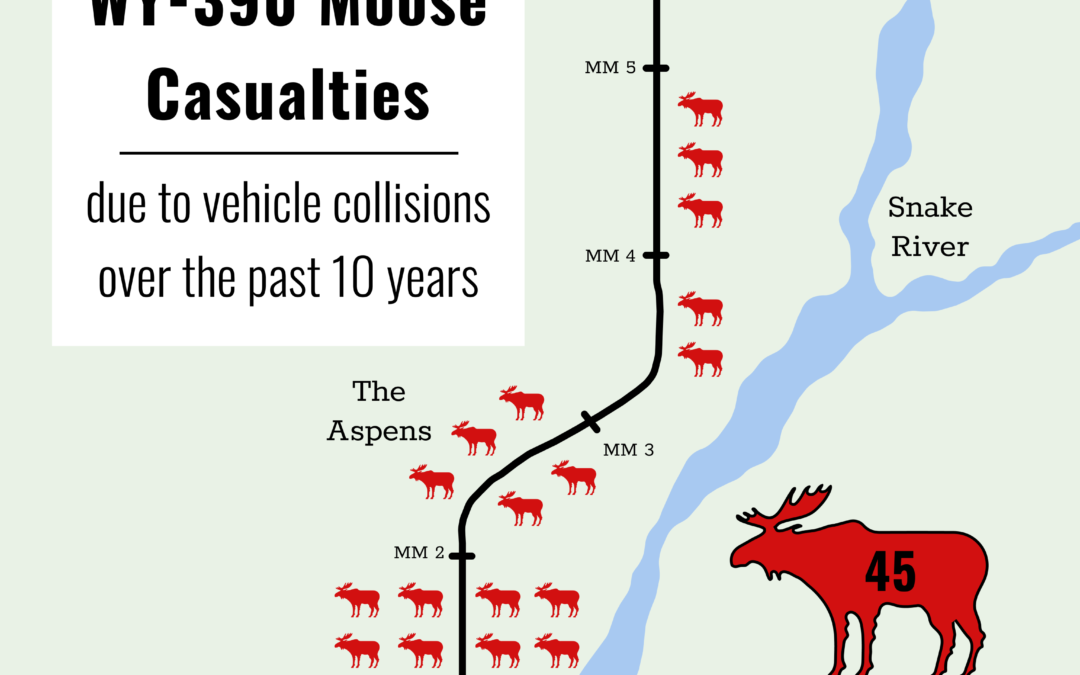

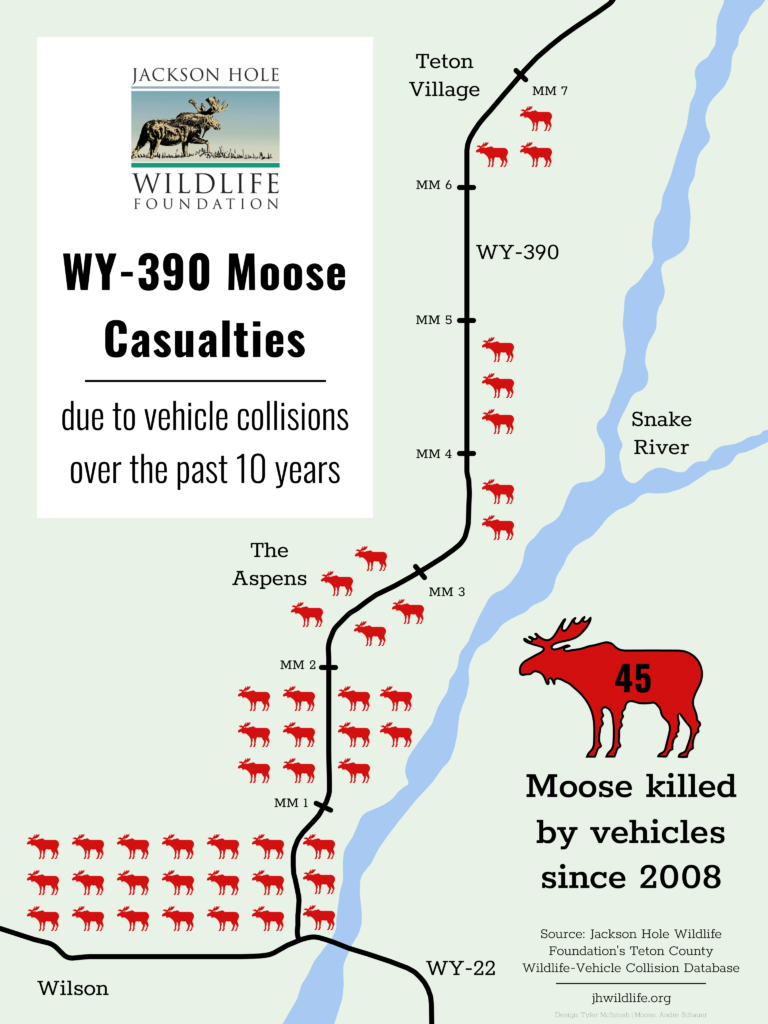

Three moose were hit and killed by vehicles on WY 390 in July, the last of which was killed during daylight hours, which is very rare – about 90% of moose collisions with vehicles occur at night. Summer collisions with moose are also relatively uncommon. The last time a moose was killed on WY 390 in the month of July was 2009. Of 45 moose casualties recorded since 2008 on that highway, only 13 (29%) have been hit during summer months (May-October), and just five along the one-mile stretch of highway adjacent to the Aspens development. While we receive many calls and emails when a moose is killed by a vehicle, we want to ensure that we refer to our collected data to consider potential responses and initiate any near-term, site-specific actions. We also consider how short-term actions fit within larger county-wide objectives. All in all, we want to make sure that our response is thoughtful and makes sense based on the many variables at any given site. While doing so, we don’t want to diminish the value of the animal that succumbed to a human-caused death. For the animal struck, statistics don’t matter. For prioritizing our actions, though, statistics are essential.

The recent “flurry” of moose casualties sounded alarms in Moose-Wilson neighborhoods and throughout the valley. While the reality is that one animal is hit on a highway each day in Jackson Hole on average, each individual moose collision – particularly within this corridor where backyard moose are beloved – is a newsworthy event, as it should be. The challenge of such newsworthy events is to make sure that they are viewed in context, while also recognizing the tragedy of the loss of another iconic animal. In short, what do we do about it?

The data reflects the fact that the largest problem on WY 390 occurs within the first few miles. Since 2008, 82% of all collisions on WY 390 have occurred in the first 3 miles, with nearly half of all collisions occurring in the first mile. If you add WY 22 to the mix (1/2 mile to the east and west of the WY 390 intersection), six moose have been killed within 1/2 mile of the junction to the east, and three moose have been killed within 1/2 mile to the west. All told, 30 moose have been killed in the past decade within one mile north of the WY 390 / WY 22 intersection and one mile to either side of that junction.

In terms of trends on WY 390, only five moose were killed between 2015 and 2017 (three of the five were hit in the first mile) so we have had a relative respite from the 26 that were killed from 2011-2013. Many campaigns launched simultaneously by citizens and organizations may have helped to reduce collisions along the length of WY 390. The combination of those measures (nighttime speed limits, fixed radar feedback signs, digital message signs, public awareness campaigns) is helpful, even if the small sample size makes drawing direct correlation between any one of those measures and the reduction in collisions inconclusive. The trend along most of WY390 is positive, but the intersection area remains the largest concern. We are also keenly aware of the possibilities and limitations with respect to potential structural measures through that densely inhabited corridor. We need to do what we can, where we can, as soon as we can.

In consultation with WYDOT, recently we decided to change the language on digital message signs to reflect the number of animals hit in July, stressing the severity of the issue to drivers. Many other near-term actions have been discussed, ranging from modifications to the existing reduced speed limit zones to improving sight-lines via vegetation removal to enhanced education campaigns with rental car companies and Teton Village hotels. It is never a bad thing to make people aware of the impacts that driving can have on wildlife, from ungulates to raptors. These collaborative efforts will continue between agencies and partners, spanning the entire Teton County highway network.

Teton County has also just released its Wildlife Crossings Master Plan, and accompanying Action Summary. Unsurprisingly, the WY 22/WY 390 intersection ranks as the highest priority for action. As with all locations, agency and organizational partners discuss immediate opportunities to change things for the benefit of wildlife and human safety. We don’t wait around for a long-term fix if any helpful measure can be initiated today. Some of those near-term options are still being considered for the intersection area. However, given the severity of the issue there and the possibility of much more frequent roadway occupancy by moose (given the proximity of ponds and willows on all sides), the ideal scenario is to separate animals from the highway via wildlife underpasses. The terrain lends itself well to that solution since the road is elevated and the areas of interest to moose are well below the road grade. While fencing long stretches in any direction in that area will be challenging (longer fencing typically increases effectiveness), modest fencing in the immediate area of the intersection should not impair views and serve the purpose of “funneling” animals to the underpasses (probably the best solution). The exact outcome (solution) has not been arrived at given the complexity of the area and many potential options, but it is important for the public to recognize that those discussions are ongoing. The public itself will have an opportunity to weigh in, as WYDOT seeks input on its planned work on the Snake River Bridge and WY 22/WY 390 intersection, slated for 2023.

If you would like to learn more about potential wildlife crossings plans there and across the county, you can access the Action Plan (recommendations of advisory committee) and the full Master Plan at the county website here. Page 7 of the action plan identifies the WY 390/ WY 22 intersection as the highest priority site, and it briefly discusses potential solutions. https://www.tetoncountywy.gov/1639/Wildlife-Crossings

The Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and Greater Yellowstone Coalition are tremendous resources for wildlife crossings work. You can visit with them about this issue, as well as the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, at the Alliance’s Summer Block Party at the Center for the Arts on August 29 from 5:30 pm – 9 pm. Come out and tell us what you think! In the end, we just want to ensure that we’re doing the right thing, in the right place, for the safety of people and for the good of wildlife.

by jhwildlife | Aug 13, 2018 | Blog, Wildlife Friendlier Landscapes

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

Saturday, August 11 was the sort of sunny scorcher that forces even the most ebullient dogs to slink into the shade. These are the days that force siesta. Yet despite the 95-degree heat, 35 dedicated souls showed up to the Hardeman Meadows north of WY 22 to help Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and the Jackson Hole Land Trust improve fences for safer wildlife passage. Some of Saturday’s volunteers have been on most of our projects this year, which is remarkable itself, but especially gratifying when any of them could have chosen to sit this one out and stay cool. That’s just not the way these wildlife-nuts operate, though. They’ll be there. They’ll get it done. Amazing.

Eleven middle school students also joined us, arriving with three instructors from Teton Science Schools, to dislodge (demolish!) top rails on a fence that will be replaced. It wasn’t hard to inspire the kids to whack away with their mini-sledgehammers! They did great work and lifted us up in the hot afternoon with sunny dispositions. Thanks, boys!

By 2 pm, we had removed more than 3/4 of a mile of fence, and hammered staples into posts on a fence now lined with smooth wire that can be dropped to a single strand when the pasture is not in use – a standard Wildlife Friendlier Fencing modification. Importantly, all of the volunteers stayed well hydrated – few moments passed without someone shouting “are you drinking water?!” – and completed the project safely.

JHWF is grateful to its volunteer fence team leaders – Randy Reedy, Scott Landale, Steve Morriss, and Gretchen Plender – and to Teton Science Schools as well as the Jackson Hole Land Trust (especially Erica Hansen and Steffan Freeman) for another rewarding day making the landscape just a bit better for wildlife! We’ve now removed or improved 5.5 miles of fence this summer.

We’ll get after it again on August 25. Join the herd!

– Jon

by jhwildlife | Jul 27, 2018 | Blog

Wildflowers abound this time of year, throughout the valley and up amongst the high peaks of the Tetons and Gros Ventres. Alpine prairies provide vivid photo-ops as we hike past vast fields of green, yellow, purple and red. As humans we tend to naturally appreciate these broad vistas but forget that this palette of natural color only exists thanks to a minuscule, but miraculous phenomenon between plants and their animal neighbors. Most of us have heard of pollination, but many of us probably have not looked into what a truly complex and rather strange process it is.

Pollination is a symbiosis, a relationship between living organisms, but more specifically it is mutualism – a symbiosis where both species in the relationship benefit. When insects, birds and even bats land on a flower and drink the nectar provided by the flower, parts of their bodies come in contact with that plant’s pollen, which are essentially the plant’s male reproductive cells. When the pollinator travels to its next nectar source, that animal shakes off some pollen from the previous flower and helps fertilize the female reproductive cells in the new flower. Essentially, the pollinator gets a reliable source of food, the plant gets fertilized, or rather “pollinated.” Seems like an odd way to reproduce, right? Scientists believe that this strange relationship between animals and plants evolved very early in the history of flowering plants, or “angiosperms.” It is also believed that the evolution of pollination quickly enabled flowering plants to reproduce super effectively, thus allowing for rapid diversification of this particular group of plants; partially explaining why angiosperms are today, one of the most diverse groups of living organisms with about 300,000 known species.

-

-

Broad-tailed Hummingbird

-

-

Field Crescent Butterfly

-

-

Bumblebee

Humans still have much to learn about pollinators. Just within the last few decades have we understood the importance these animals have to our existence – studies have shown that 1 out of every 3 bites of food people eat is created by pollinators. Yet many bee and butterfly populations and ranges are still unknown even throughout the United States, although we now know that several are struggling. Bees have been in many headlines lately – “Save the Bees” has become a common tagline. However, with the focus being on non-native honeybees that are not actually threatened with extinction, native bee species that are more efficient and more widespread pollinators are often left out of the spotlight. Many of these species (including a few found in Teton County) suffered estimated population declines of 80-95% due to habitat decline and possible pesticide poisoning.

Anise swallowtail

Today, 33 species of butterflies and moths are listed as federally endangered, and only in the last 3 years have native bees been recognized and listed as being threatened with extinction. All species of pollinators protected by the federal Endangered Species Act can be found here.

There are various field guides and online resources for identifying birds and butterflies throughout Wyoming, but far fewer for less conspicuous insects like bees and beetles. Linked below is a field guide to western bumblebees produced by the U.S. Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership and modified for Wyoming, by the Wyoming Biodiversity Institute, as well as a great article by researchers at the University of Wyoming explaining various types of bees in detail. Most bee species can be difficult to tell apart (even under a microscope), but bumblebees require less of a learning-curve because their identification usually relies on color patterns on different body parts, just like butterflies and birds! Why not extend your wildlife searches to a smaller scale, and challenge yourself to identify pollinators like butterflies and bumblebees?

Additional Resources:

https://wyobio.org/files/2614/1174/2125/printablebeeguide.pdf

http://www.uwyo.edu/barnbackyard/_files/documents/magazine/2016/summer/wynativebees0716.pdf

https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/features/posters/WesternBumblebeesPoster_print.pdf