by jhwildlife | Nov 27, 2018 | Blog

By Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

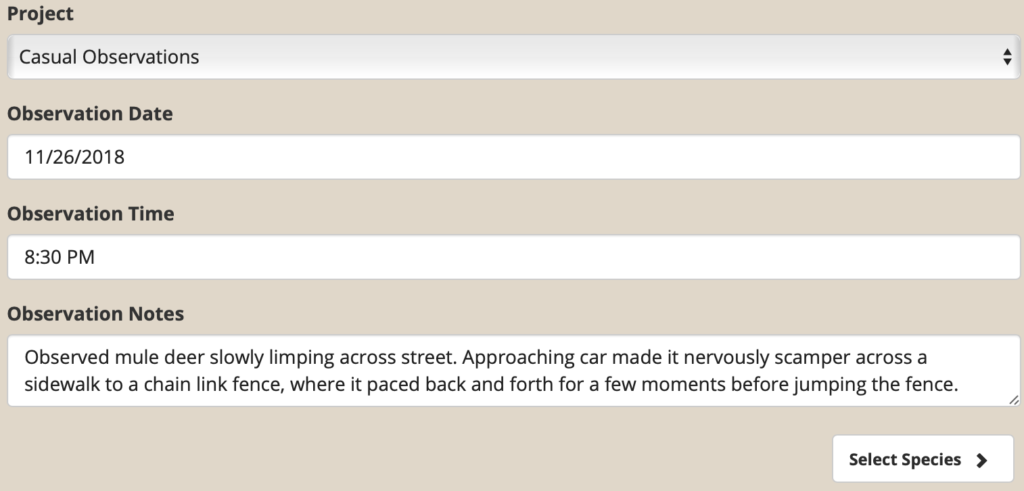

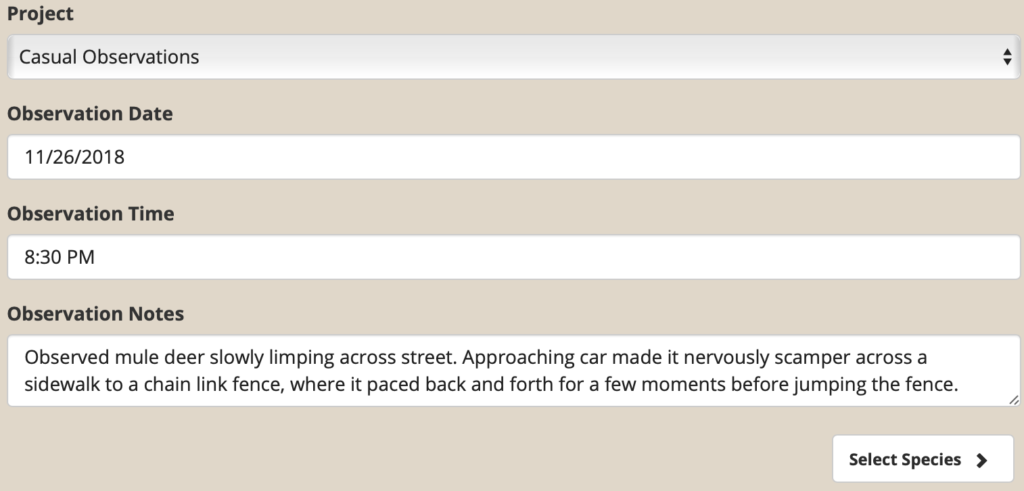

Last night as I was walking in a quiet Jackson neighborhood, I noticed a mule deer limping in and out of the shadows cast at the edges of a street lamp’s reach. The deer was about 40 feet from where I stood. I stopped in my tracks, as these intimate interactions stir me. My heart dropped, though, as I watched it hobble across the street. What may have happened to this beautiful animal? Any number of natural things. And to those natural things we add obstacles of our own making.

Breaking the solitude, a car approached and startled the deer. It quickly hobbled across the street, ambled rather gingerly over a snow pile, stepped across a sidewalk and then halted at the foot of a chain link fence. After a few paces along the length of the fence in each direction, it reared back and leapt. While it didn’t flip, its legs or hooves definitely hit the fence as a ringing metal clatter disrupted the stillness.

And then the deer disappeared into the darkness of unlit yards.

I pondered what I had seen for a few moments, and then continued my walk. I was still thinking about it this morning when I mapped the observation at the Nature Mapping Jackson Hole site.

We know there are a lot of deer, moose, ravens, chickadees and squirrels living with us in Jackson. The value of recording our observations with these creatures (and all others) is that it provides us with information that can help us adjust our lifestyles to live more compatibly with wildlife. In the case of this injured deer, winter itself presents a significant challenge. Predators pose a threat. The scarcity of available food can pose a threat. And we certainly pose a threat, with every development that adds to their gauntlet of challenges. In that very brief interaction, I considered how the road, snowbank, sidewalk, fence, and houses impeded that deer – a 30 second window into its lifetime of navigating challenges.

This particular interaction inspired me to think about how we can do things better – to make life easier for our wild neighbors. Not every interaction is so. Often I map observations simply to record the joy of an experience with a wild thing. All of these observations matter, since none are inevitable into the future. Our best chance to ensure that people see deer in Jackson for the next century is to think carefully about how our lives impact theirs, and modify our behaviors and actions to facilitate a rewarding co-existence. Nature Mapping provides a tool to collect and share this knowledge. As founder Bert Raynes once wonderfully said, Nature Mapping is about “keeping common species common.” What an opportunity we have to do the right thing in this wild community!

What did you see today?

Northern Harrier

by jhwildlife | Nov 26, 2018 | Blog

– written by Aly Courtemanch, Wildlife Biologist, Wyoming Game and Fish Department

It’s that time of year again when bighorn sheep migrate from their summer ranges high in the mountains to the lower elevation valleys to spend the winter. Miller Butte on the National Elk Refuge is a well-known wintering area for a portion of the Jackson Bighorn Sheep Herd. The herd numbers approximately 400 sheep; about 80 of those spend the winter on the Elk Refuge. The bighorn sheep breeding season, or rut, occurs in late November and December. The Elk Refuge Road is one of the best places to observe this natural spectacle. Bighorn sheep have the latest rut of all of the ungulates in Jackson Hole because they have one of the shortest gestation (pregnancy) lengths (approximately 6 months).

A common sight near Miller Butte in the winter is bighorn sheep licking or eating dirt on the road, as well as licking passing cars. Bighorn sheep, like other ungulates, have a strong desire for salt. They are often seen at natural salt seeps in the mountains, ingesting crumbly rock and dirt. Because of this, bighorn sheep are attracted to road sides during the winter because we use various mixtures of sand and salt compounds (usually sodium chloride or magnesium chloride) to de-ice roads. Bighorn sheep on Miller Butte have also learned that cars and trucks often have salt encrusted on their bumpers and wheels, which makes for a tasty treat. The types of salt commonly found on vehicles and on the Elk Refuge Road are not toxic to bighorn sheep and don’t pose a direct threat to their health. However, this unnatural behavior causes bighorn sheep to congregate in close contact with one another and licking cars exposes bighorn sheep to others’ saliva, which can cause disease transmission. Recent research in this herd has shown that some sheep are carriers of pneumonia-causing bacterial pathogens. These bacteria are passed from sheep to sheep via saliva, mucus, and droplets in the air. One sick sheep licking a car could easily infect other sheep that are licking the same car, which could lead to disease spreading quickly through the whole group. You can help prevent this behavior by only stopping in designated pull-outs, continuing to drive slowly through groups of bighorn sheep that are congregated on the road, and educating other visitors.

The last pneumonia outbreak in the Jackson Bighorn Sheep Herd occurred in 2011 and 2012, when approximately 30% of the sheep died. Symptoms of pneumonia include severe coughing and runny nose. In recent years, a few sheep have exhibited these symptoms at Miller Butte, but a herd-wide outbreak has not occurred. We appreciate receiving reports from Nature Mappers and the public of any sheep they observe coughing. A description of how many sheep and their ages/sexes (ram, ewe, or lamb) is very helpful, as well as a video if possible. Please report your observations of any sick sheep to Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation or Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

Photographer Credit: Mark Gocke

by jhwildlife | Oct 19, 2018 | Blog

Published by Kyle Kissock

Last month, I had the chance to spend National Public Lands Day representing the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation (JHWF) on a habitat improvement project outside of Pinedale. This project was the first in what will be a series of collaborative rangeland stewardship efforts with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) this fall.

Our work on National Public Land’s Day was exciting because it took place directly in the “path of the pronghorn.” The path of the pronghorn is a migration corridor utilized by herds that summer in Jackson Hole and the Upper Green River Basin to reach wintering ranges farther south. This corridor runs through the heart of the famous local natural gas field, the Pinedale Anticline. Hardly visible from the road, if you drive west off of Highway 89 south of the East Fork River crossing, you’ll find yourself squarely in the middle of the Anticline’s industrial infrastructure. This area is also leased for cattle grazing, and as such, endless miles of barbed-wire fence run between drill sites in what is extremely important habitat for pronghorn in transit.

Our objective was to modify this barbed wire by installing passage gates which will allow pronghorn to move through the fence while keeping cattle inside. Because pronghorn prefer to travel under rather than over fences, these passages enable pronghorn to move through a fence upright, without having to wriggle under a hazardous low wire. Locations chosen for gates were deliberately selected by biologists at the intersection of the fence lines and well-traveled pronghorn trails. The trails were surprisingly well defined by scat and tracks, and were remarkably discernible carved into the fine-grained dirt. You can even see one in the picture passing through the gate; I thought they were really neat natural features that confirmed just how often (and how many) animals move through the area.

The volunteer team successfully installed 16 pronghorn passages over the course of the day. The most common variety of passage was composed of three, removable wooden posts tiered horizontally across an opening in a fence line. The posts can be manually offset from the gate to allow pronghorn passage through the fence, and just as easily be slid back in place if cattle were grazing in the area. We also installed several “slip gates,” which were a series of three to four wooden posts driven vertically into the ground at no more than 16 inches apart. The narrowly were spaced wide enough to allow a pronghorn to shimmy through, while keeping stock on the desired side. The advantage of slip gates is once installed, posts don’t need to be slid into and out of position as they are staked permanently into the ground.

Time will tell if pronghorn take to either of the gates, but we have reason for optimism. At one point in the afternoon, less than ten minutes after we installed a passage, we looked back from several hundred yards away to see several pronghorn had just crossed the fence line at the new passage site. Had they used the slip gate, or did they successfully navigate their way under the barbed wire? BLM hopes to document usage of these passages on camera, so stay tuned! In the mean-time, we’ll look forward to opportunities to keep expanding our work into neighboring communities.

by jhwildlife | Sep 25, 2018 | Blog

By Frances Clark – Lead Ambassador, Nature Mapping Jackson Hole

What to look for in October? – Almost everything!

October is a critical month of movement for wildlife as cold settles in, grasses dry, insects die, and berries and seeds are there for the picking.

We encourage Nature Mappers to look for “last of the year” (LOY) sightings of several species that either winter below ground or migrate out of the valley. For instance, keep an eye out for chipmunks—least chipmunks are mostly in the sagebrush running with their long tails stiffly upright, and yellow-pine chipmunks, with slightly wider, shorter tails, are more likely seen in forests. Both species cache food for winter, perhaps rousing from hibernation or a torpor to benefit from these treasures mid-winter. A few osprey were lingering a few days ago as the younger ones leave after their parents. Will you spot the last? Also, we have had LOY records for Bank and Rough-winged Swallows, Wilson’s Warbler, Double-crested Cormorant, and Clark’s Grebe for October in 2011. Kestrels will disappear along with their insect prey–crickets, as will Mountain Bluebirds. Will you take the last record for the year?

Many other birds are moving through: the last of the Sandhill Cranes (listen, then look high!), hawks, many ducks, mixed flocks of songbirds as well as more obvious flocks of blackbirds, starlings, and crows. Do your best. Other critters are shifting around the valley as the weather cools and grasses wither. Pronghorn start making their way towards the Gros Ventre and eventually down to Pinedale along the “Path of the Pronghorn.” Bison move around and away from the bison hunt. Elk are bugling and jousting (territorial and reproductive behaviors), and Bighorn Sheep may show up near Miller Butte in the National Elk Refuge. Watch out for moose now because they are in full rut. Juveniles look on as mom and strange bulls are dashing about in a craze. Bears are in hyperphagia, eating all they can before winter. Eight black bears were seen one morning along Moose-Wilson Road last week—do you know why? Think berries.

Birds that are more visible at lower elevations include Gray and Stellar’s Jays. Goshawks also come lower—checking out bird feeders for small birds. Cedar Waxwings come in for berries.

In short, October is a great month for Nature Mapping. Get out and enjoy the show while giving back to the wildlife we all care for.

by jhwildlife | Sep 25, 2018 | Blog

By Debra Patla – Research Associate, Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative

If you see or hear an amphibian this month, wish it “Good Night and Good Luck!” Amphibians (frogs, toads, and salamanders) mostly vanish from our view in September and are not seen again until April or May. Where do they go? How do these small, fur-less animals not only survive Jackson Hole winters, but also manage to do so for long lives of up to 15 years or more?

As ectotherms (“cold-blooded” vertebrates), amphibians have the advantage of being able to go for months without any food at all. The popular idea that they just go down into the mud to sleep for the winter does not actually pertain to any of our locals. Each species here has its own special adaptations, and these are so successful that we see some populations persisting over decades, showing up to breed in the same wetlands every spring. The basic recipe is being able to get to the right places in late summer/fall, which typically means dispersing or migrating. This crucial element of their lives makes amphibians very vulnerable to development, landscape alteration, and roads, even if wetlands are protected.

Jackson Hole has four species of native amphibians. Here are their winter-survival recipes:

Boreal Chorus Frog: Find a good dry place and chill!

Boreal Chorus Frogs over-winter terrestrially (not in water) — at or near the soil surface, such as under rocks and logs, in leaf litter and loose soil under snow, among tree roots, and in animal burrows. Some of these frogs may even find a place in your basement, house foundation, or out-building, if they have survived the trip to your yard from the pond where they metamorphosed from tadpoles or mated as adults.

The miracle ingredient of their strategy is that chorus frogs can tolerate freezing. Only a few species of amphibians in North America can do this. Physiological adaptations allow them to stop breathing, heartbeat, and blood flow, while the water outside their cells and vital organs freezes. Then they thaw out and make the trek to a wetland where you will again hear their amazing concerts in the spring.

By the way, you may hear this species in October: they sometimes make a small trill in fall during the daytime, usually from dry places within a few hundred yards of a pond. This sound is much shorter and softer than their breeding call and is a bit like the softest clacking call of a Clark’s Nutcracker (but on the ground). No one seems to know why they do this!

Columbia Spotted Frog: Find water that does not freeze, with oxygen please!

Columbia Spotted Frogs spend the winter in spring-fed streams, ponds or lakes with springs or upwelling water, submerged bank chambers at the edges of water bodies, and in underground springs. Do they sleep all winter? No, studies indicate they often move around in their winter areas to find more oxygen or warmer water. Spotted frogs often aggregate at winter sites, a kind of party we can only try to imagine! But the tendency to gather at crucially important, hard (for us)-to-recognize sites threatens our ability to conserve local population of this species.

Western Toad: Find a cozy underground nook!

Western Toads exhibit yet another winter strategy: they cannot tolerate freezing, but they do not over-winter in water like spotted frogs. Toads seek out rodent burrows, squirrel middens, crevices or chambers underground, decayed root tunnels of large trees, or abandoned beaver lodges. What’s important is to get away from the frost zone. Toads may migrate long distances (e.g., over 1 mile) to reach their over-winter sites, and they spend the winter communally, suggesting that suitable sites are quite rare in the landscape. These behaviors pose a big challenge to successful conservation of local populations.

Western Tiger Salamander: Just go deeper!

Adult Western Tiger Salamanders spend most of their lives underground even in summer in rodent burrows (such as those made by pocket gophers) or under logs or rocks. They can also dig their own burrows in soft soil. Winter dictates that they get away from the frost zone and the danger of freezing by going deeper down in the underground. Their behavior is hard for modern researchers to investigate because they do not carry radio transmitters well on their long slender bodies, and implanted transmitters do not work underground.

Tiger salamanders are Jackson Hole’s ‘Trickster’– they have a knack of showing up and surprising people in yards, cellars, garages, dog water bowls, under buckets and porches, window wells, irrigation ditches, fish hatchery runways — good grief, what’s next? There are quite a few observations of large numbers of salamanders crossing roads, usually at night, in the rain. This again shows how vulnerable amphibians are to habitat fragmentation and increasing traffic in the face of their vital need to find safe winter places.

Boreal Chorus Frogs over-winter out of the water near the ground surface. Photo Credit: Jaime Hazard.

Deb Patla is a herpetologist who lives near Moran in Buffalo Valley. She has conducted long-standing amphibian surveys in Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks as well as the National Elk Refuge. She is also a Nature Mapper and vets our amphibian and snake observations. Please keep on mapping those creeping, leaping, and slithering creatures!