by jhwildlife | Jul 26, 2019 | Blog

Guest Blog by Ben Wise | Biologist – Wyoming Game and Fish

Pronghorn Antelope can be found throughout the grasslands and sagebrush landscapes of the valley and have a long history of finding ways to survive in the harsh landscapes of western North America. Pronghorn are are the last remaining member of the family Antilocapridae, with their closest living relatives being giraffes and okapi (both of Africa) and are one of the last remaining unchanged North American terrestrial mammals from the Pleistocene era. Pronghorn are the fastest terrestrial mammal in North America and evolved over-sized heart, trachea and lungs to enhance the ability to reach speeds of up to 55 mph over short bursts and sustained running at greater than 35 mph for four miles or more. Their long, light skeletal structure reduces stress on joints during sustained sprints and their hooves have large cartilaginous pads that act as shock absorbers while running over rocky, uneven terrain. This incredible speed was essential to evade prehistoric North American predators including two species of cheetahs, dire wolves, short faced bears and saber-toothed cats as well as modern predators including coyotes, mountain lions and bobcats. Other adaptations essential to survival on the open grasslands include incredible eyesight due to oversize, protruding eyes (roughly the same size as an African elephant) that allow them a 320 degree field of vision and the ability to detect movement up to 4 miles away. Hollow hair which is both light weight and incredibly efficient for both warming in the winter and cooling in the summer is also easily pulled out, allowing pronghorn an additional line of defense if caught by a predator. Finally, pronghorn antelope derive their name from the unique forked horns that both male and females grow, with males producing much larger horns. These horns are a combination of both horns and antlers with interesting qualities of both. True antlers are made of bone, grow throughout the spring and summer and are shed in the late winter of each year. True horns posses a bony core over which dense keratin grows and neither the bone or the outer core is shed during the life of the animal. Pronghorn are unique in that they grow a black keratinous sheathe over a bony core (similar to a horn) and after the breeding season each fall, shed the sheaths and begin regenerating another set of sheaths for the following year (similar to antlers).

Every spring between 300-400 pronghorn antelope migrate from the windblown sagebrush flats of the Green River Valley, following the Gros Ventre River drainage down to Grand Teton National Park and surrounding lands to give birth and raise their offspring. As winter approaches, these hardy individuals with four month old fawns in tow leave the Jackson valley, often enduring early fall snow that has inevitably began accumulating on the mountain pass that separates their winter and summer habitats, and retrace this “Path of the Pronghorn” as they have done for millennia.

Pronghorn derive their names from short horns that both males and females grow. Photo: Mark Gocke

by jhwildlife | Jun 24, 2019 | Blog

Guest Blog by Sarah Hegg | Biologist – Grand Teton National Park

The American Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) is one of the Endangered Species Act’s (ESA) most remarkable success stories. Grand Teton National Park was an integral part of their recovery in the Jackson Hole area.

Peregrine Falcons are cliff-nesting raptors that mainly eat other birds. They are perhaps most famous for their speed. Biologist have clocked peregrines at speeds of up to 200 mph, speeds that rival race cars. Along with their speed, their extraordinary aerial acrobatics, rapid diving, and graceful soaring make them one of the most impressive birds to watch. The lower elevations of the major canyons in Grand Teton National Park provide extensive opportunities for cliff-nesting and diverse habitats for foraging.

With the introduction and use of the pesticide DDT in the 1940s, many bird species, especially predatory raptors, experienced drastic declines throughout North America. Peregrine Falcons were among the birds most affected by DDT and its toxins. It is believed that peregrines were almost completely extirpated within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem by the 1960s.

Peregrine Falcons were listed under the ESA as endangered in 1970. The restriction and banning of DDT, along with other organochlorine pesticides within North America, in combination with habitat protections and a reintroduction program helped contribute to the recovery of Peregrine Falcon populations. In 1980, efforts to reintroduce Peregrine Falcons to Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks were initiated locally by The Peregrine Fund, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, and the U.S. Forest Service. These local efforts were in conjunction with similar efforts elsewhere in the Greater Yellowstone Area and western United States.

To reintroduce Peregrines in the park, large hack boxes (5’ x 4’ x 3’) were built using plywood sides, a barred metal front and a gravel floor. These hack boxes were placed at several sites within the park and Jackson Hole. Between 1980 and 1986, 52 fledgling falcons were released at 3 different hack sites. Several captive-bred peregrine chicks were placed in the hack boxes each year and fed multiple times daily through a remote feeding chute so the young falcons could be fed without associating food with humans. When the chicks were old enough to fly, the bars on the front of the hack boxes were gradually removed. The first wild nesting attempt in the park was documented in 1987 near Glade Creek, which was also the location of the first successful wild breeding occurrence in 1988.

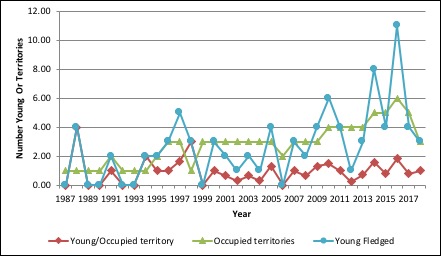

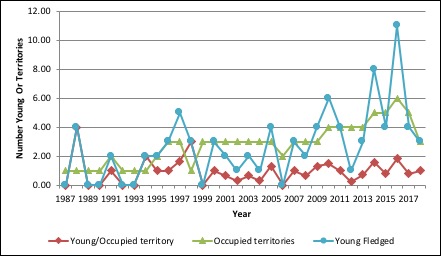

Annual peregrine falcon reproductive data in Grand Teton National Park, 1987-2018.

Peregrine Falcon populations have slowly recovered throughout North America and were removed from the ESA in 1999. Each year since 1987, park biologists conduct surveys of known and potential peregrine territories to document the number of occupied territories and their reproductive success. While the number of territories has gradually increased, reproductive success is still fairly low and can vary greatly from year to year.

One of the new territories established was in lower Cascade Canyon in 2010. This eyrie (the name for a peregrine nest) is located near Baxter’s Pinnacle, a popular rock climbing route. This area is thought to have been historically occupied in the early 1900s. Peregrine falcons are very sensitive to human disturbance. They will abandon their nest to defend their territory, which can lead to nest failure and low reproductive success. Since 2011, the park has established a closure for the Baxter’s Pinnacle climbing route and its descent gully area each year when and if biologists confirm the territory is occupied (typically sometime in April) and lasts until the pair fails or the young successfully fledge (generally mid-August). In addition to protecting young Peregrines, this closure also helps to protect climbers. Peregrine Falcons are fiercely territorial and aggressive birds, especially while nesting and incubating eggs. They become even more protective after their chicks hatch. The bird’s speed and aggressive territorial behavior pose a safety risk to climbers who could be knocked off the route and injured.

The Baxter’s pair have successful fledged young, six of the eight years that the territory has been closed, and is one of the most consistently successful Peregrine territories in the park. The support from the climbing community by respecting this closure area is crucial for the falcon’s continued success, and is greatly appreciated. This example of cooperation helps the park carry out its mission of preserving native wildlife and habitat while providing enjoyment and recreation opportunities.

Numbers in Grand Teton

- In 2018 park staff monitored 8 known and recently active territories, 3 of which were occupied.

- The 32-year historical average for successful occupied territories is 47%, and the recent 10-year average is 60%.

- The 32-year historical average productivity is 1.53 young per breeding pair, while the recent 10-year average is 1.77 young per breeding territory.

- The maximum numbers of peregrine territories occupied is 6, and the maximum number of young fledged is 11, both occurring in 2016.

Identification

- Slightly smaller than a crow

- Black/dark gray “helmet” and a black wedge below the eye

- Uniformly gray under its wings. (The prairie falcon, which also summers in Grand Teton, has black “armpits”)

- Long tail, pointed wings

Habitat and Behavior

- Near water, meadows and woodlands, cliffs

- Nests on large cliffs over rivers or valleys where prey is abundant

- Resident in the park March through October, when its prey—primarily songbirds and waterfowl—are abundant. Migrates to Mexico or even further south for winter

- Lays 2–4 eggs in late April to mid-May

- Chicks begin to fledge in late July or early August

- Dives at high speeds (can exceed 200 mph/320 kph) to strike prey in mid-air

Cover Photo by C. Adams

by jhwildlife | Jun 6, 2019 | Blog

by Jon Mobeck, Executive Director

“Preserve and protect the area’s ecosystem in order to ensure a healthy environment, community and economy for current and future generations.” – Teton County Comprehensive Plan’s Vision Statement, adopted 2012

In July 2019, the Jackson Town Council and Teton County Board of County Commissioners voted to add to a November, Specific Purpose Excise Tax (SPET) ballot measure that will allocate (if voters approve) $10M for wildlife crossing solutions at sites prioritized within the County’s Wildlife Crossings Master Plan.

While there are many worthwhile and necessary projects on the slate, we believe that wildlife crossing solutions address the vision of our Comprehensive Plan (quoted above) precisely, warranting commensurate investment. Oddly, and despite the fact that the community has repeatedly stated that wildlife is a paramount value, the community has had very few opportunities to voluntarily invest in the preservation of wildlife or our ecosystem. In the case of the SPET, the burden of that investment is shared by both local residents and tourists. That cost-share for the benefit of wildlife makes sense, since our local economy rests on the health of a globally significant ecosystem that requires wide-ranging stewardship.

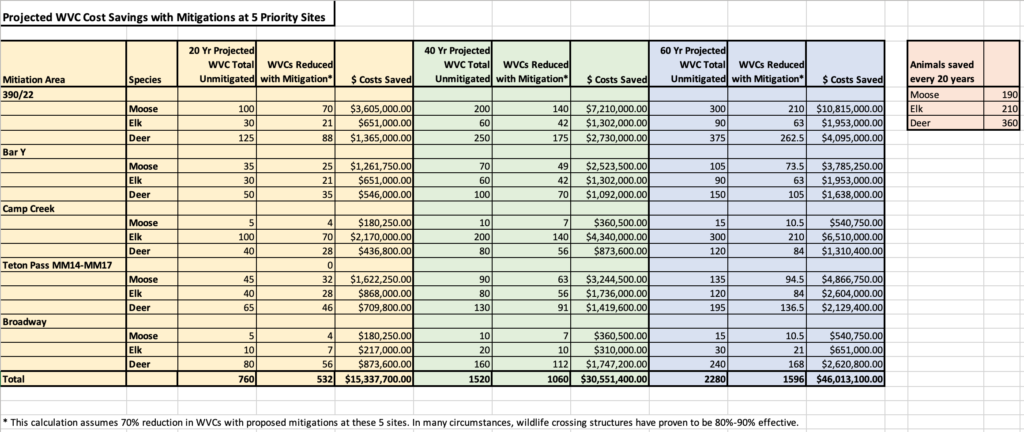

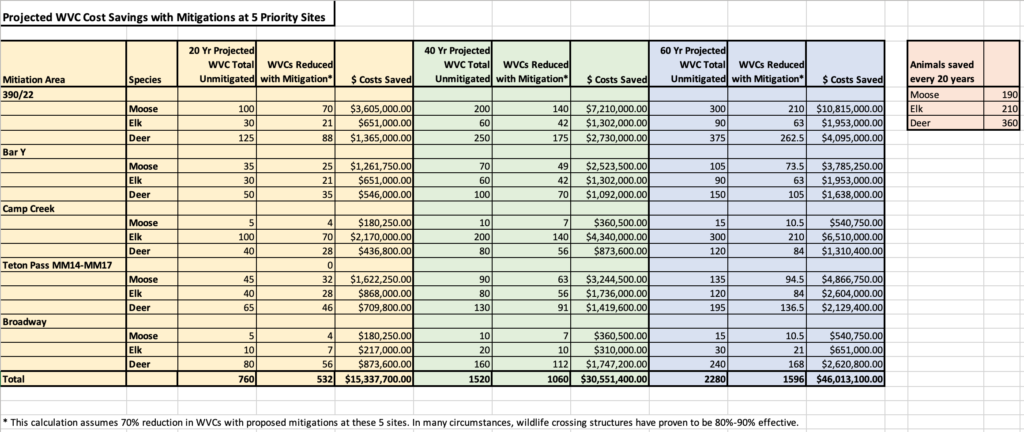

What about the question of “how much?” While we intuitively value “saved wildlife,” safer highways and connected habitats, those intangible benefits are difficult to measure. Most cost-benefit analyses look at the tangible costs of wildlife-vehicle collisions (WVC) to ungulates (many other small and large animals are hit by cars in our valley, including hawks, eagles, owls and osprey). Those costs include vehicle damages, bodily injury, carcass removal/disposal and the “game value” of the animal as assigned by the Wyoming Game & Fish Department. The “wildlife-vehicle collision costs per species” varies from state to state, but for our purposes in Wyoming, we estimate those costs as follows:

Moose = $51,500

Elk = $31,000

Deer = $15,600

The differences in these costs correlates to the size of the animal and the related severity of a collision. To analyze the efficacy of wildlife crossing structures at these specific prioritized sites, we project the current 5-year WVC trends (from the Teton County Wildlife-Vehicle Collision Database that we manage) into the future and assign a WVC Cost Per Species as listed above. We then calculate the cost saved through estimated WVCs reduced. None of these numbers reflect the value of moose, elk or deer to our tourism economy, nor do they reflect the value of the animal within our particular ecosystem or community. Jackson Hole values moose and elk extremely highly, partly due to their intensely-monitored populations, but also because they are iconic symbols of this wild place, and veritable neighbors to many around the valley.

Wildlife crossing structures have been shown to reduce ungulate WVCs by 80-90% when appropriately fenced, but they are not the only or best solution everywhere. In some cases, the geologic/geographic/hydrologic properties of a location preclude effective structural solutions. In other places – especially roadways of 40 mph or lower – a variety of tools can be deployed to positively affect WVC-reduction at a good “cost-per WVC reduced.” Those tools are being used in the town of Jackson, along the WY390 route, and soon in the town of Wilson to slow drivers and increase the probability of avoiding collisions with animals. We use the same cost-benefit formula to assess the efficacy of any tool deployed in any location, enabling the best solutions based on the variables present at each site.

We feel that the four “top priorities” considered within this measure are best addressed with structural solutions. The spreadsheet below includes WVC projections and the economic value of WVC costs saved over 20-year intervals at five prioritized locations (WY390/WY22 intersection, WY22/Bar Y, WY189/WY181 Camp Creek/Hoback, WY22 Teton Pass West MM 14-17, and West Broadway in the town of Jackson – the non-structural solution in this mix). These numbers do not incorporate inflation, and while they are estimates based on current trends in each location, the extrapolated numbers (rounded for simplicity) do not consider changing population or distribution dynamics over time, which is likely to occur to some degree. Each site was analyzed as a two-mile stretch of highway, with the exception of West Broadway, which is a one-mile site. Click on the spreadsheet below to enlarge.

What we find is that appropriate mitigation measures installed at these 5 sites should pay for itself in WVC cost savings in about 20 years, and perhaps less. While appropriate mitigation measures at all sites will likely exceed $10 million dollars, if we conservatively assume that the measures we can take in these 5 locations will ultimately reduce current WVCs by 70% (recognizing some limitations in a few of these sites), we would save just over $15M in 20 years. After that 20-year period, future savings (an additional $31M over the ensuing 40 years of a structure’s expected 75-year lifespan) exceed the cost of the solutions implemented. That is a good use of public money, especially when considering that this public money is invested expressly to realize the vision of the County’s Comprehensive Plan. We aim to be conservative in our estimates as we place a high value on the efficient use of public funds.

![]() I hope that you will agree with Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and countless other community members that a $10M SPET investment in solutions for these sites is an extremely prudent investment for our community. It’s not always easy to measure the value of a publicly-funded item, but in this case, we can make an easy economic case for the value of our foresighted action. These actions, combined with other site-specific solutions elsewhere, will make our highway network safer for drivers and wildlife.

I hope that you will agree with Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and countless other community members that a $10M SPET investment in solutions for these sites is an extremely prudent investment for our community. It’s not always easy to measure the value of a publicly-funded item, but in this case, we can make an easy economic case for the value of our foresighted action. These actions, combined with other site-specific solutions elsewhere, will make our highway network safer for drivers and wildlife.

To learn more about WVC solution opportunities at many of the County’s prioritized sites, please review this Wildlife Crossings Master Plan Action Summary to which Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation contributed.

by jhwildlife | May 23, 2019 | Blog

Guest Blog by Josh Metten | Senior Naturalist, Jackson Hole Ecotours

“Look! There’s a herd in the pasture over there!” I point out a herd of elk to my group of students and their parents from Grace Episcopal School in Monroe, Louisiana. Unlike a normal EcoTour of Grand Teton or Yellowstone National Parks, we’re on private land in the Snake River Bottom. It’s day three of our tour, and today we’re working with the Jackson Hole Land Trust and the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation to remove fencing which has been impeding the movements of the very herd of elk we’re now looking at.

It’s our third year of fence removal stewardship with Grace and the JHWF. The first year we busted buckrail in an elk calving area within Grand Teton National Park. The next year we coiled old barbed wire on public land south of Jackson, watching later as a mule deer doe walked through our handiwork. But this year we’re doing something different, working with the JHLT, JHWF, and private landowners to help steward core riverbottom habitat. It’s an area we would not otherwise be allowed to venture, but our benefactors, the elk, know nothing of property rights.

Saving Wyoming’s Great Migrations

Despite this week’s spring snowstorms, the green wave is now racing across the Wyoming landscape. Fresh grasses and flowers are bursting from the moist soils, to the delight of our elk, mule deer, pronghorn antelope and other ungulate herds. These species all share a key adaptation in common, they migrate to survive the harsh Wyoming Landscape.

These migrations, many of which are thousands of years old, take herds across busy highways, where they risk collisions with speeding cars. They cross property boundaries, jumping over barbed wire or buckrail fences, some are injured or even killed in the process.

Why go through all the trouble? Research with GPS collars has shown that migrating animals are able to stay with spring longer, taking advantage of the most fertile period of plant growth for an extended period. This strategy only works however, if the habitat remains protected and the animals can effectively travel their migration routes.

Stewardship in Action with the JH Wildlife Foundation and JH Land Trust

Look across the Jackson Hole valley and much of what you see is now protected public land. With the creation of the National Elk Refuge in 1912, and expansion of Grand Teton National Park in 1950, ancient migration routes, were protected, but hundreds of miles of fencing from old ranching operations remained.

Over the last 20 years the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation and an army of volunteers have worked to remove or modify this fencing, rewilding the National Park. The remaining lands, about 3% of Teton County, are private, and lay primarily along the riparian corridor of the Snake River. The cottonwood galleries, creeks, ponds, and spruce/fir forests found here offer disproportionately rich habitat for wildlife. As such they are of critical conservation concern.

That’s why the Jackson Hole Land Trust has worked with landowners to conserve over 55,000 acres of private lands using conservation easements, which preserve the conservation values of the land in perpetuity. The parcel we’re at on this sunny Mother’s Day weekend is one such easement, an agreement patiently brokered by the JHLT and three separate landowners.

Don’t Fence Me In: Boots on the Ground Conservation

After a quick orientation from Erica at the JHLT, Gretchen Plender and Jon Mobeck of the JHWF, we set off to remove old buckrail fence at the top of a ridgeline which overlooks the river corridor. The weathered fencing already has some gaps, and Jon shows us the packed dirt trails of hundreds of elk who have passed through these limited openings.

“We’re going to create more openings by removing this old fence so the herds can move more freely.” he tells us. With mini sledge hammers and fencing tools the students, recent 8th grade graduates, tear into the fencing. Post by post quickly drop as the mile long section begins to vanish into the sagebrush.

Studies show that in the Western U.S. one ungulate per year dies from entanglement in fencing for every two miles. Young calves who become separated from their mothers by fencing can double this statistic. With the fencing in this section removed elk migrating to the river from winter habitat on the National Elk Refuge now have a clean route through a historically challenging corridor.

We finish for the day having removed over half of the section, the rest of the EcoTour Adventures team will return tomorrow, Mothers Day, to complete the job. It’s a fitting time to do fence work for wildlife. We pass a herd of cow elk beneath the cottonwoods as we depart, most of which are likely pregnant. In a few weeks these forests will become a nursery for hundreds of newborn calves. They will quickly grow through the summer months, and when the first snows come in the fall the calves will follow their mothers out of the river bottom. They will pass by remnants of fencing, unaware of what formerly stood in their path.

What you can do to Conserve Wyoming’s Wildlife

Want to help wildlife in Jackson Hole and across Wyoming this summer? We’ve got a few ideas for you:

Public Fence Pull Projects with the JHWF: Join the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation for boots on the ground conservation removing or modifying fencing to facilitate wildlife passage. Dates are listed here: https://jhwildlife.org/our-work/current-projects/

Contact: kyle@jhwildlife.org

Buy a Wildlife Conservation License Plate: Wyoming Residents! We invite you to join Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures and many of our guides in purchasing a Wildlife Conservation License Plate. Proceeds from these plates directly fund wildlife crossings and other mitigation strategies to reduce car collisions with wildlife. It’s a win win for wildlife and people. http://www.dot.state.wy.us/wildlife_plate

Now in our 11th year of operation, Jackson Hole Ecotour Adventures leads half day, full day, and multi day wildlife, cross country ski, and snowshoe tours in Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks 365 days a year. Let us help maximize your Jackson Hole Experience Today! 307-690-9533 or info@jhecotouradventures.com

Josh Metten is a Senior Naturalist with Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures with nearly a decade of experience guiding and sharing stories about the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

by jhwildlife | May 17, 2019 | Blog

As the sun warms in mid-May, the aroma of sagebrush fills the valley once again. Sage-grouse leks are quieting down, bird migrants are staking out territories, and resident mammals are shifting their habitats. Nature mappers can see and hear a good number of species specialized to the sagebrush-steppe by taking a drive through the “flats” of Grand Teton National Park.

Many species depend upon the expansive sage-dominated habitat that covers much of the valley floor. Mountain Sagebrush is adapted to the well-drained glacial soils and provides shelter, food, and breeding sites. Greater Sage-grouse, Brewer’s Sparrow, and pronghorn require sagebrush and are deemed “obligates”. For others it is not essential but preferred habitat here in Jackson Hole. Savannah and Vesper Sparrows, Western Meadowlarks, Sage Thrashers, and Green-tailed Towhees build nests in the dense shrubs and search for insects and spiders for food. Red-tailed Hawks and Northern Harriers hunt for rodents, such as least chipmunks, Uinta ground squirrels, and voles. Hummingbirds zoom in to pollinate larkspurs and scarlet gilia.

The next few weeks is a great time to see and nature map wildlife. Songbirds are singing atop sagebrush to establish territories and attract mates. You may see males fly at intruders or observe courtship behaviors – bowing, feeding, and fluttering. Later on, most birds go quiet while raising chicks and so are much harder to find.

Mammals are also active. Pronghorn arrive just about now and soon will be giving birth. Coyotes will be looking for fawns hidden among the sage shrubs, although ground squirrels are much easier to catch. “Red” bison calves will be cavorting, and mule deer are moving about belching out volatiles of their favored forage: sagebrush. The smell of sagebrush leaves comes from terpenoids and coumarins, which serve as chemical defenses. Wildflowers begin blooming in abundance in June – paintbrush, hawksbeards, sulphur buckwheat, lupine, and balsamroot, adding to the splendor of the scene.

So take an early morning or evening drive through the park – around Antelope Flats, up the park road. Or better yet, find a spot to sit quietly with your binoculars and a spotting scope handy. And please, keep on nature mapping. We want to be sure our common sagebrush-steppe species stay common. Your observations help us know how these critters are faring over time.

Thank you!

Frances Clark, Nature Mapping Volunteer

Pronghorn are an iconic species of the sagebrush-steppe. Photo: Mark Gocke.