by jhwildlife | Jan 15, 2021 | Blog

By Kate Gersh

Holy moly technology! We have exciting news to share stemming from our Neighbors to Nature: Cache Creek Study project (N2N), which is a partnership with Friends of Pathways, The Nature Conservancy-Wyoming, and the Bridger-Teton National Forest (BTNF). This project’s intent is to provide valuable wildlife, plant phenology, trail, and recreation use data to the BTNF. This data collection will inform the forthcoming BTNF Forest Plan revision process and influence the way we recreate on our trail system while coexisting with wildlife.

A component of this large-scale citizen science project is deployment of 27 game cameras throughout our local Cache Creek, Snow King and Game Creek trail system, and here is where the exciting update comes in to play. Over the course of the N2N project so far, the team has collected a whopping 719,173 total images from these game cameras! Most images contain “nothing there” because the cameras were triggered by wind, snowfall, or vegetation. We have been searching for a way to process a large quantity of camera trap images and especially, to pre-sort the images that have non-detections; thus, making the process of vetting images for wildlife identification faster and more fun for our volunteers. Thankfully, The Nature Conservancy-Wyoming recently collaborated with The Nature Conservancy-California to batch process all 719,173 game camera images through Microsoft’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) processor. The AI is trained to detect animals, people, and vehicles in camera trap images, using millions of training images from a variety of ecosystems.

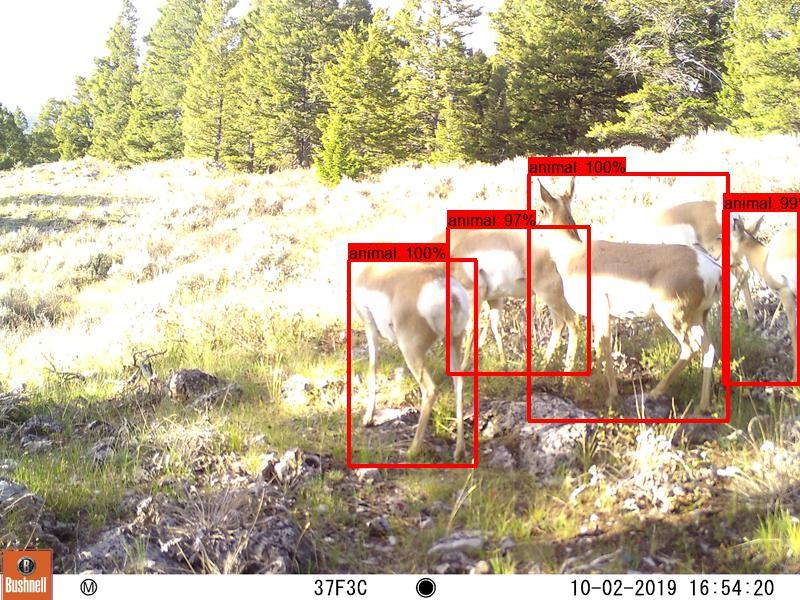

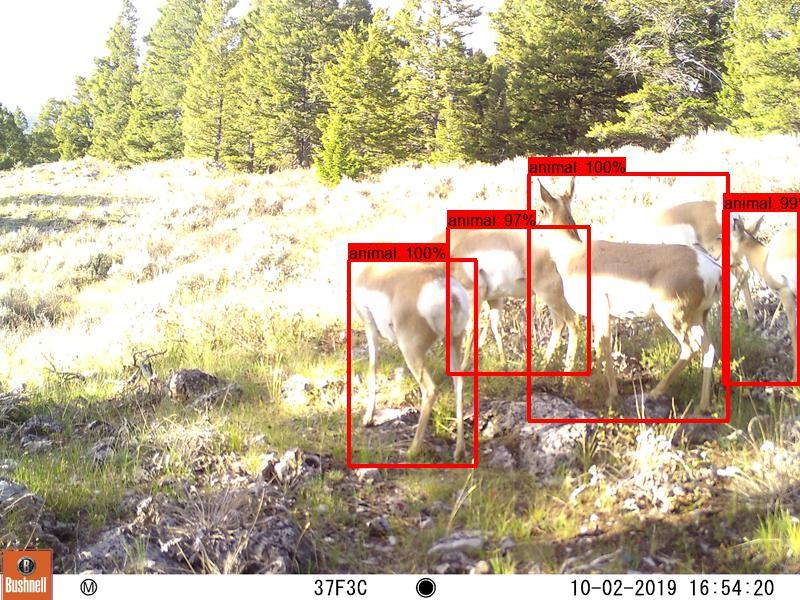

Here are some example images of what detector output looks like:

In a sample of 7500 images, non-detections (aka. images with nothing there) made up 69.9%. The AI also detects people, and with a high level of confidence we can withhold images containing human subjects from further review, which is important for privacy issues (please note: AI DOES NOT identify faces). Animal detections accounted for 290 images or 3.9% of the sample. However, Microsoft’s AI does not identify animals to species; it just finds them. So, this is only a first stage and the N2N projects still needs volunteers, like yourself, to continue verifying images through the project’s Zooniverse platform. Machine learning has accelerated this process, by letting volunteers and researchers spend their time on the images that matter the most. While this streamlining of images hasn’t happened yet, we are excited to be closing in on getting the AI-processed images into Zooniverse, so soon you will be seeing far fewer “nothing here” photos!

Join the Study, Help Classify Images on Zooniverse

We need you to help us comb through the thousands of images captured on our cameras and collect the data they provide. The information will then be analyzed by scientists at The Nature Conservancy-Wyoming. By devoting as little or as much of your time as you like, you will be providing critical data to the Bridger-Teton National Forest that will benefit both people and wildlife.

Access the Zooniverse site here.

Funny side note: It took Dr. Courtney Larson, Conservation Scientist at The Nature Conservancy-Wyoming, over a week to digitally transfer 719,173 images to the AI processor!

by jhwildlife | Oct 8, 2020 | Blog

Blog author Hanna Holcomb is the 2020 Fall Americorps intern with the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation

By Hanna Holcomb

In 2009, local volunteers and biologists launched Nature Mapping Jackson Hole under the Meg and Bert Raynes Fund as a way to document local wildlife. Since then, more than 500 citizen scientists have logged over 70,000 observations. But as Nature Mappers log sightings of elk and bluebirds and bears (oh my), they might wonder, what happens with all of that data?

I spoke with some of the people who use Nature Mapping data, which is now run by the Wildlife Foundation, to help guide land and wildlife management decisions.

“The data that’s collected from Nature Mapping programs and all of their affiliated projects gives us a lot of information that we would have a very difficult time collecting on our own,” said Ben Wise, Wildlife Disease Biologist at Wyoming Game and Fish.

Wise pointed to Moose Day, an annual winter survey of moose on private lands in the county. Though only about 3% of land in Teton County is private, those areas are important wintering habitat for several species. But because Game and Fish conducts winter wildlife surveys from a helicopter, their usual methods aren’t possible in developed areas.

“When we’re flying over an area, oftentimes animals get up and move,” said Wise. “But if you’re trying to do that over a suburban area, you’re going to be running animals through people’s yards.”

Instead, Moose Day volunteers hike, ski, and drive, looking for moose on private land. Last year, one-hundred citizen scientists saw 127 moose.

Wise estimates that without Moose Day counts, population estimates would be 30-40% lower than they are. The data collected by Nature Mappers gives Wyoming Game and Fish a better understanding of moose population trends and distribution in the valley.

Nature Mapping data is also used to assess the natural resources of a piece of land that is proposed to be developed or conserved.

“When I wrote an environmental analysis on a green space in town, Nature Mapping data was very helpful in showing a list of species that people had seen over time using that space,” said Megan Smith, owner of EcoConnect Consulting, LLC and former Nature Mapping Coordinator. “I can go there three or four times over the course of a project, but what I see versus what hundreds of people have seen over a ten-year period is very different.”

Having long term data is also useful for the Teton County Conservation District when they are asked to assess the natural resource impacts of a proposed development on private land.

“It’s not uncommon for us to look at those development proposals and then compare Nature Mapping data to the project area as well as the vicinity,” said Morgan Graham, GIS and Wildlife Specialist at Teton County Conservation District. “And the number one thing I look for is season of use.”

For example, if Nature Mapping data shows that mule deer consistently use an area in the winter, the conservation district may emphasize the importance of reducing noise and disturbance to help mule deer conserve energy through the season.

If you’re interested in becoming a Nature Mapper, email kate@jhwildlife.org to sign up for a certification training.

And if you’re on the fence about becoming a Nature Mapper….

“The fact that you’re not an ornithologist or a trained wildlife biologist shouldn’t dissuade anybody from participating,” said Wise. “There are a lot of common animals like deer or elk, that people can report, and that’s all very valuable data for us.”

And of course…

“It’s fun,” said Graham. “And you can feel good about supporting long-term data collection.”

by jhwildlife | Sep 15, 2020 | Blog

By Frances Clark

The members of the Corvid or Crow family are smart, often showy, and have a reputation. As a group they are omnivores, eating a range of food from carrion to berries to bugs. They are known for their intelligence, such as remembering locations of food stashed months previously and faces of humans who have treated them well or ill. Each species is distinctive in appearance and voice and their behaviors reflect their habitat and social communities. As permanent residents of Jackson Hole, Corvids can be a fascinating group to observe and nature map in the coming months as many of the summer visitors move on.

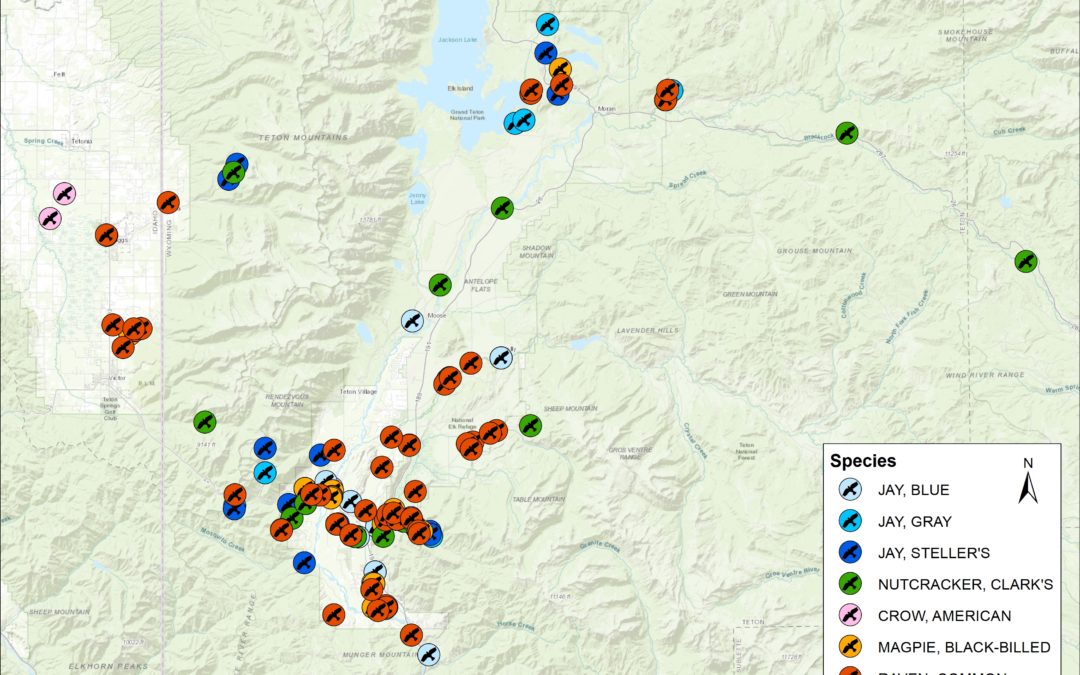

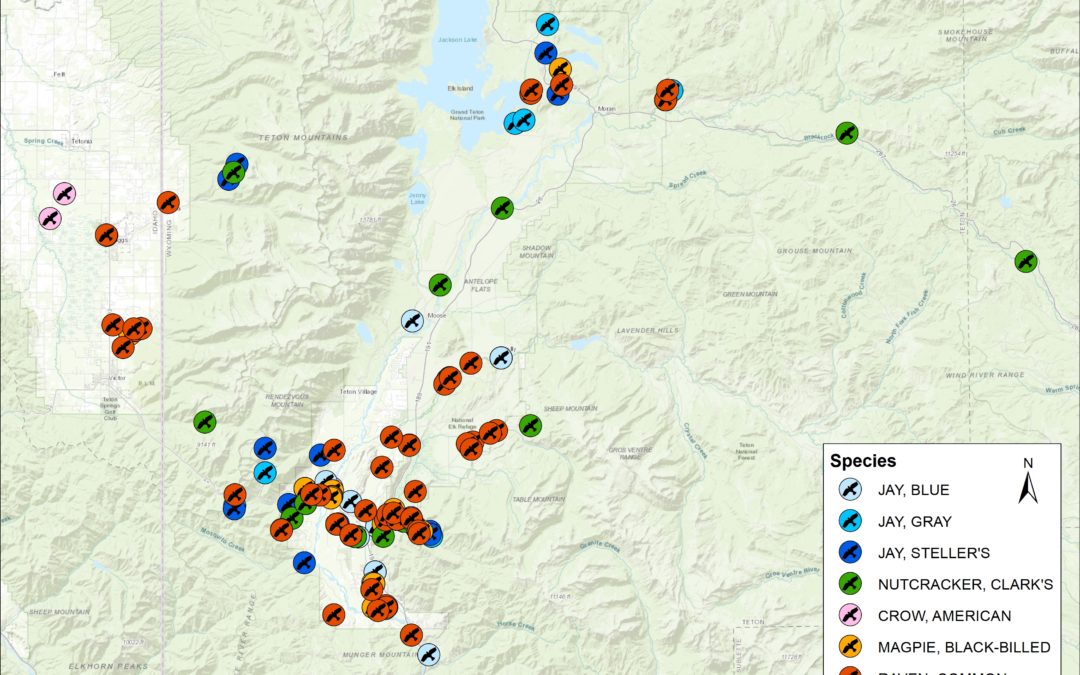

Click here for a map of local Corvid sightings

The most common sightings are Common Ravens and Black-billed Magpies. They are well known as scavengers of carrion, raiding nests for baby birds and eggs, and preying upon small mammals—in short not very appealing behavior from our human perspective. However they are also nature’s clean-up crew, as they are willing to eat most anything.

American Crows are unusual in Teton County, and perhaps overlooked due to their similarity to the larger Ravens—It can be hard to determine size against the scale of sky and mountains. Crows are smaller with less bulky beaks and a flat-ended tail when flying, vs the raven’s heavier beak and “wedge-tail” visible in flight. Crows tend to be seen more in flocks around town where they are well adapted to human spaces, while ravens are generally in pairs or family groups out in the larger landscape. The typical caw caw caw voice of crows is higher pitched that of the husky croaking sounds of ravens.

Clark’s Nutcrackers are renowned for their mutualistic relationship with white-bark pine. These gray, white, and black birds move around the West in family groups seeking areas with productive white-bark pines. At this time of the year, they will use their substantial beaks to peck and pry out pine seeds from closed cones, gulp dozens into a “sublingual pouch” and then stash them on snow-free mountainsides. Each bird can remember 1000s of locations! Notably, males have an incubation patch to warm the eggs hatched in the heart of winter, so the females can retrieve their own stores. Over subsequent months, parents will continue to count on seeds for their survival, but also leave enough propagules to start a new generation of white-bark pines. These smart, flashy birds play a critical role in sustaining high-elevation ecosystems.

Canada Jays and Steller’s Jays are two other Corvids found mostly in our evergreen forests. Canada Jays, called “Gray Jays” until 2018, are also known as Camp Robbers and Whiskey Jacks. They are gray, plumpish birds with whitish heads touched with black. They have the smallest beaks of corvids in Jackson Hole. They fly about in bonded pairs often making a series of starling squawking sounds.

Canada Jays are boreal birds, adapted to cold evergreen forests with spruce, but here in northwest Wyoming, they are also found in mixed stands of evergreens and aspens. True to their name, they are well adapted to tough, cold conditions. Their feathers can puff up and cover both feet and bills and also allow for solar radiation to penetrate deeply for extra warmth.

Mated for life, pairs scatter-stash their food to get by over the long winter months. These Jays have glands that produce a very sticky saliva, and they use their bills to make blobs of their food and stick them under bark and lichen an on twigs and needles. Favorite foods are berries—including huckleberries, arthropods, and fungi. Like Nutcrackers, they remember 1000s of locations. They produce young in February and March when it can be -20F, using their frozen food packets to nurture both parent and offspring. They will not have a second brood even if the first fails, despite the coming of easier spring conditions.

Another unusual behavior of Canada Jays, is by late spring, the largest of the brood pushes its siblings from the parental territory and gains the benefit of pilfering the stashes of its parents and learning sites for next winter’s stores. Its siblings have to look for adoptive parents who may have lost their brood and have food reserves to share.

Canada Jays can be beguiling. When scouting for food, they glide and hop from limb to limb, tilting their heads to check out what you may have in hand. I saw several groups a week ago along the south shore of Leigh Lake, a favorite place for picnickers. Their arrival was heralded by startling cranky calls and whistles.

Steller’s Jays are more elegant in appearance, but perhaps less interesting in behavior than Canada Jays. They are found in similar habitats and eat similar food. Steller’s Jays in addition will look for white-bark pine nuts and stash single seeds, but do so much less efficiently than Clark’s Nutcrackers. They also watch and remember where other animals store their food and pilfer as needed.

Steller’s Jays have a complex social system called “site-related dominance”. In essence, the dominant pair defends an area around its nest with the male dominant over the other males, and the female ruling over nearby females. Other pairs are kept 5-25’ away from this central nest, whereas couples farther out are more gregarious with each other. Scientists have determined all sorts of posturing and sounds associated with this complex community.

Hawks—Red-tail, Goshawk, Cooper’s–as well as ravens are all threats to Steller’s Jays. The jays respond to their presence by “mobbing” the intruder—squawking, diving, and otherwise driving it off. This is the advantage of living in a neighborhood of jays.

While our Jays don’t migrate, in winter higher-elevation breeders can move down-slope. This is when we may see Steller’s Jays at our feeders instead of up on Teton Pass. Occasionally there may be an irruption of flocks of young birds moving about. These are all interesting movements to Nature Map.

Finally, rarely, we see the Eastern Blue Jay, a close relative of the Steller’s Jay. They both have the arched crest, iridescent blue feathers, and decorative highlights. The more boldly marked Blue Jays tend to prefer acorns typical of more eastern forests, while Steller’s seek pine seeds of our montane forests of the Rocky Mountains. Last year, Nature Mappers recorded several Blue Jays in and around Jackson.

As we all remain hunkered down during this year of covid-19, let’s get out and enjoy the Corvids. Learning their differences in identity, habitat, location, and particularly their behaviors enhances our appreciation of being in Jackson Hole. And you help our local understanding of these birds by Nature Mapping what you see!

Frances Clark

For more information:

All About Birds https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/ a free site from Cornell Labs.

“Birds of the World” formerly Birds of North America – website sponsored by Cornell Labs: https://birdsoftheworld.org/ a subscriptions site with lots more detail

Regarding the name change of Gray to Canada Jay: https://www.audubon.org/news/the-gray-jay-will-officially-be-called-canada-jay-again

Differences in calls and meaning of Ravens vs. Crows: A YouTube by Cornell Lab of Ornithology: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZ5iippq3rA

by jhwildlife | Aug 24, 2020 | Blog

By Renee Seidler

Sign, sign, everywhere a sign… And these ones are meant to preserve the scenery, as opposed to the signs in Les Emmerson’s song (1970).

I know many of you have been long awaiting the fixed radar speed limit sign installations in Wilson. Where are those signs?!

We thank you for your keen interest in this joint project with Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation, Teton County and WYDOT. All parties are excited to get these installed to help make Highway 22 in Wilson safer for our wildlife and safer for motorists. The company we contracted with to purchase the signs has been hard-hit by COVID-19 and their ability to produce the signs had been limited. However, the County recently received the signs and we expect them to be installed before the end of summer!

An example of a flashing radar signs. Signs that flash have shown to be more effective at garnering the attention of drivers.

On a similar thread, we will also be upgrading the fixed radar signs on Highway 390. You may have noticed that we had to decommission the speed limit part of those signs. The digital speed limit message had lost its ability to synchronize with the WYDOT signs that flash lights during reduced nighttime speed limits. This led to driver confusion about the speed they should be driving. Once we install the Wilson signs, we will continue to partner with the County and WYDOT to address the signs on Highway 390 as well.

The Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation has a long history of using multiple techniques to address wildlife-vehicle conflict on our roads (note the term: wildlife-vehicle conflict which is more encompassing than saying wildlife-vehicle collision and includes issues with landscape fragmentation and permeability, road noise impact, invasive species encroachment and much more), one of these practices is the deployment of road signs with the intent to slow drivers down and make them more aware of and attentive to their surroundings and the possibility of wildlife on the road. Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation has built a reputation in Teton County for being the “wildlife sign organization” (but if you’re not in the loop, ask me about our good work in roadkill data collection, our contribution to the Wildlife Crossings Master Plan, our involvement in passing the SPET to provide $10 million in funding for wildlife crossings and our participation in the Wildlife Stakeholder Group for crossings in Teton County) and rightfully so. You will note that we have been very focused on funding and purchasing noticeable signs. This is not by accident of course.

One of the most important parts of a wildlife message sign is that they need to capture motorists’ attention. The classic yellow diamond-shaped wildlife sign, often with a depiction of the animal of concern like a deer, tends to have very little effect on a driver’s speed or attentiveness to the fact that wildlife are more likely to be on the road. How often do you notice the yellow diamond signs?

Signs have the greatest impact on driver behavior if they have a dynamic, novel message, are located unpredictably and have flashing lights (Hardy et al. 2006). To have a higher impact, they need to be placed selectively where the wildlife problem is. So, we write messages on our message boards that will catch a driver’s attention and will be specific to a seasonal issue (like, “young ospreys on highway, drive carefully”), then move the sign to it’s next location where its sudden appearance will catch drivers’ attention once again in a new location. Drivers’ responses to wildlife warning signs are also limited to ~500 meters before and after the sign (Al-Ghamdi and Algadhi 2004). After about a half kilometer past a sign, drivers begin to lose attention to the message. Signs that demonstrate evidence of an issue also tend to be more effective, so sometimes you will see our signs mentioning the number of animals killed to date that year at that location (Blacker and Jones 2013).

Wildlife warning signs and reduced speed limits can only have noticeable effectiveness when the speed limit of a road is already relatively low (Huijser et al. 2018, Riginos et al. 2019). This is because at higher speeds like ~55 mph or more, vehicle stopping distances are much greater and typically the distance at which a driver notices the animal is not far enough away for the vehicle to stop before colliding with the animal (Huijser et al. 2008). You will see our signs are often posted in wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots that have lower speed limits like around the junction of Highways 22 and 390 or just north of town on Highway 191. Occasionally, you will see our signs on highways at higher speed locations as well, when we have heightened concern for wildlife-vehicle collisions or we are hoping to create greater awareness around a seasonal issue, like on Teton Pass or east of Hoback on Highway 191.

Unfortunately, what motorists think they would do and what they actually do may not be congruent and, we road ecologists have a mantra: it’s so much easier to change wildlife behavior than it is to change human behavior. This has been borne out time and again in many sociological and ecological studies and begs that, when finances are not a concern, wildlife crossings are much more effective than wildlife signs at reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions and at getting animals successfully across the road, i.e., addressing landscape permeability concerns (Clevenger and Huijser 2011). But as stop-gap measures or where wildlife crossings are not feasible physically or financially, signs are often the next best thing. The best thing we can do as drivers is to pay attention to our surroundings (for instance, if you are driving next to a river or over a bridge, recognize that these are riparian zones where animals are more likely to be present and crossing the road), look ahead, scan the sides of the road, drive the speed limit or the speed indicated by conditions (slower when visibility is limited!) and remind your friends that it is au courant to be a good driver!

by jhwildlife | Jul 23, 2020 | Blog

By Renee Seidler

This month, the Teton County Board of Commissioners unanimously approved the Agreement to Render Services (ARS) that allows Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) to conduct the planning, engineering, design, permitting and construction of two wildlife crossing structures near the intersection of WY-22 and WY-390. These structures will be funded by Teton County using Special Purpose Excise Tax (SPET) money, which was supported by 79% of voters in November 2019. These two crossing structures are part of a larger project that will protect wildlife and motorists alike from collisions at this busy intersection. Because of this ARS, the County and WYDOT can continue to move forward together on their collaborative project to protect wildlife in and around this busy intersection.

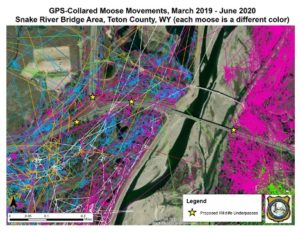

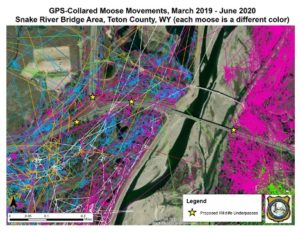

Map showing Wyoming Game and Fish (WGFD) GPS-collared moose movements in the Snake River Bridge Area. Yellow stars indicated future wildlife underpass locations.

As the Environmental Assessment for the Tribal Trails Connector moves forward, Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation is working closely with our agency partners to provide expertise and data to help inform the decision-making process. You can listen to the Board of County Commissioners most recent workshop on Tribal Trails here. The discussion starts at the 46:45-minute mark. Most of the conversation speaks to design ideas for the Coyote Canyon/Indian Springs intersections, but commissioners also touched on topics of wildlife crossings to mitigate wildlife-vehicle collision and wildlife permeability issues on WY-22. To stay abreast of this topic, link to the project website.

I am lucky to be a part of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation team that has played such a vital role in providing and interpreting roadkill data for the county, state, and other partners. Amongst our many other accomplishments, we have been an active member of the Wildlife Stakeholder Group that informs wildlife crossings projects for the county and state; we have helped inspire the community to support building wildlife crossing structures through approval of the Special Purpose Excise Tax; and we have provided input on location and design of wildlife crossing structures. I am continuing this legacy of working closely with our partners, both NGOs and agencies, and I have been welcomed into the conversations as an expert in road ecology. I look forward to growing these relationships and adding to the healthy discussions concerning the conservation of wildlife in Jackson Hole.

My best to you,

Renee Seidler

Executive Director JHWF